The Beginning of Seoul as the Capital City

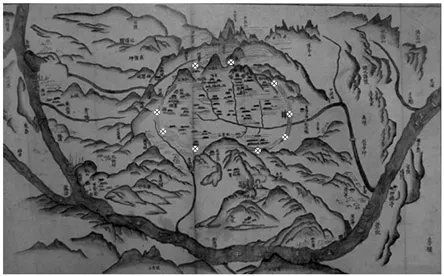

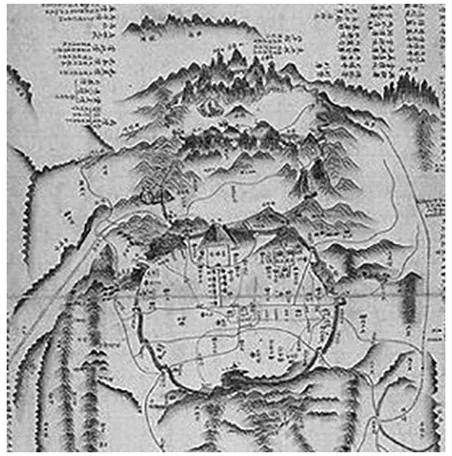

Although records of the first settlements in what is now Seoul stretch back to prehistoric times, the history of Seoul as a capital city goes back to 1394 when Yi Seung Gye, the first king of the Chosun Dynasty, decided to make this city the capital of his new kingdom. According to Chosonwangjo-sillok (The Annals of the Chosun Dynasty), Yi asked Muhak, a Buddhist monk who later became an advisor to the king, to search for an auspicious site for the new capital. Following feng shui beliefs, many philosophers and leaders deemed the act of selecting a capital pivotal in determining the fate of a dynasty. Muhak thought that Seoul’s landscape, surrounded with mountains and relatively flat in the middle, was auspicious in this regard (figure 1.1) (Joseon Wangjo Sillok, 1394).1 The official name of the city at the time was Hansong, or Hanyang. Soon after the designation of Hansong as the capital, palace complexes and administrative units were built. Confucianism became the central political ideology of the Chosun dynasty, which distinguished the new regime from that of Koryo, the previous dynasty, which adhered to the Buddhist religion. Confucian ideology was fundamentally different from Buddhism since it is a secular ideology that emphasizes virtues such as filial piety, a value that was extended to the relationship between the king and his subjects. The ruler had to possess moral rectitude in order to guide his people and to reciprocate the loyalty of his subjects. Reflecting Confucian ideology, the city gates were named after the principle virtues of Confucius’s philosophy.2 Soon after the construction of the palaces, existing marketplaces and residential districts were expanded, making Hansong the centre of political and economic activity.

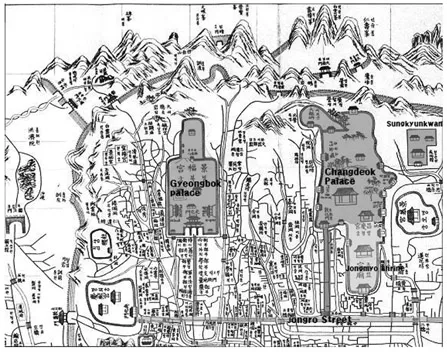

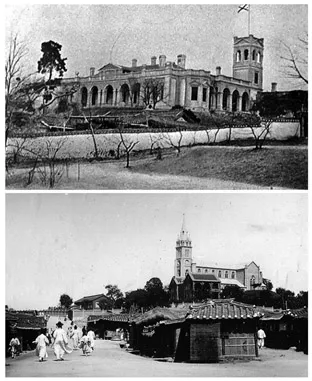

Important buildings constructed during the early days of the Chosun Dynasty include the Gyeongbok Palace Complex, the Jongmyo shrine, a memorial for deceased kings and queens; and Sungkyunkwan, the national educational facility (figure 1.2). Sited between two mountains, Gyeongbok Palace was laid out in an orthogonal fashion, similar to the layout of the imperial palace in China. A hierarchical organization of space and a symmetry of forms along the central axis characterize this main palace complex of the Chosun Dynasty. In later periods, other kings built different palace complexes, but they were less formalized in their layout. Indeed, compared to Gyeongbok Palace, the Changdeok Palace Complex, built in the early fifteenth century, shows less concern for geometrical symmetry and adopts a natural landscape resembling the palaces of the previous Koryo Dynasty. Confucian ancestral rites were held in the Jongmyo Shrine, and consequently, it was designed to accommodate ancestral tablets and the necessary articles used for the rites. As the Chosun Dynasty continued, the number of tablets increased, and the structure was elongated to accommodate a total of nineteen tablets. Very large timbers and foundation stones were chosen as building materials to create a solemn and majestic ambience.

Figure 1.1. Old map of Seoul showing waterway and main gates (indicated by crosses). The river shown below is the Han River.

The street in front of Gyeongbok Palace was called Yuk-jo Street, where six major government ministries were located. With Gwanghwa-mun, the southern gate of Gyeongbok Palace in the centre, ministry buildings were located on either side of the street. Yuk-jo Street was connected to Jongro Street, which connected the eastern and western parts of the capital. A bit west to the Gyeongbok Palace and perpendicular to Jongro Street was Donhwamun Street which connected Jongro Street to the Changdeok Palace. Most governmental functions were centred on Jongro Street since it was close to both palace complexes. The state allowed the establishment of commercial shops on Jongro Street, and the merchants of officially recognized sijon (市 廛) (official markets) enjoyed market monopoly on their specialty products in return for tax payment. Since the area was close to government offices as well as the residences of high officials, Jongro area became the centre of economic activities.

The city wall which connects four major mountains of the capital, namely Buckak, Nak, Nam, and Inwang Mountains, was constructed to protect the city. About 18 kilometres long, the city wall was continuously reinforced and repaired throughout the Chosun Dynasty. There were a total of eight city gates, which controlled entry to the capital. With the Han River, the city wall built along the mountainous terrain effectively protected the city from possible threats. Initially built using both earth and stone, it was gradually replaced with boulders over the years as floods destroyed weaker parts of the city wall.

Figure 1.2. Old map of Seoul showing the Gyeongbok and Changdeok Palace complexes, the Jongmyo shrine, and Sungkyunkwan, the educational facility, Jongro Street, Yuk-jo Street, leading from Jongro Street to Gyeongbok Palace, and Donhwamun Street, leading from Jongro Street to Changdeok Palace.

Meanwhile, less attention was given to Buddhist temples, which had occupied an important symbolic and cultural space during the Koryo Dynasty. In the Koryo Dynasty, many Buddhist temples were located in the city centre, serving as a focal point of the city and also as a landmark. By contrast, most of the Buddhist temples constructed in the Chosun Dynasty were located in the mountains or in peripheral regions. In 1510, a group of Confucian scholars set fire to the Heungcheonsa Pagoda, a famous Buddhist pagoda that was a landmark in Hansong. Although this seemed like a random act of violence, it was emblematic of the destruction of the old politico-religious order at the hands of proponents of a new order. At the beginning of the Chosun Dynasty, the preference of Confucianism as a ruling ideology was triggered by political motives, and as such, did not affect the traditionally privileged position of Buddhism in everyday life. For instance, Yi Seung Gye, the first king of the Chosun Dynasty, maintained a close relationship with Buddhist monks, being a Buddhist himself. Yet, with the consistent policy of subsequent kings to suppress the power of Buddhist priests, the end of Buddhism as a state-sponsored religion had become a fait accompli by the sixteenth century.

The social hierarchy at the time of the Chosun Dynasty consisted roughly of four large groups. The Yangban were the ruling class. They were of two types: the literati, and the military officials. In principle, a commoner could become a yangban after passing state examinations and acquiring an official position from the king. Although the class system, especially with regard to the literati, was in practice hereditary, the presence of the exam system based on talent has led some historians to note that the Chosun political system contained an element of meritocracy rather than being a strict aristocracy (Woodside, 2006). Below the literati were the Jung-in, the middle men who served as lower class officials, military, or technicians. Commoners were mostly farmers, although some depended on commercial activities or handicrafts for their livelihood. Lastly, the Chunmin class consisted of slaves, prostitutes, shamans, butchers, and others whose jobs were considered vulgar and low in the Confucian ideology. Chunmin were not allowed to take the state exams which were open to all other classes.

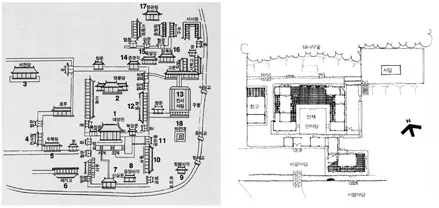

Learning and interpreting Confucian classical texts became a very important activity both culturally and economically, since the written state exam tested students’ understanding of Confucian philosophy. Although the state exam became ineffective in the later period of the Chosun Dynasty due to corruption, it provided a very competitive system through which members of the elite class had to win the right to run the country. Primary education was usually given at the residences of local literati. The highest educational institution, which corresponded to today’s national university, was the Sungkyunkwan. Admission was limited to about 200 students at a time, and only those who passed preliminary tests could register. The students at Sungkyunkwan were considered possible future officials of the dynasty (figure 1.3). The shrine to Confucius and the central lecture hall occupied the centre of the site, while dormitories were placed at the sides.

Residential districts were not strictly segregated according to class hierarchy. Yet the most prestigious area was the district near the palace complexes, as geographical proximity to political power was a very important marker of one’s status. The area north of Cheonggye Stream and between the Gyeongbok and Changdeok palace complexes was considered most advantageous. The less well-to-do lived on the outskirts of the city or outside the four city gates. Houses for different classes used different materials, and this often resulted in different forms. Residential structures for well-to-do yangban usually had tiled-roofs, while commoners and the poor lived in thatched-roof houses. As they ruled a Confucian country, the leaders of the Chosun Dynasty promoted virtues such as frugality and moderation. Concerned about the sumptuous residential structures of the upper class rivalling palace structures, a building code that dictated the size of houses according to royal rank was formulated in the early years of the dynasty. As for commoners, they did not have the resources to afford expensive wooden bracket construction. Therefore, they turned to rammed earth and rice straw, widely available as Chosun was an agrarian country, for building materials. Unlike that of Europe, traditional Korean architecture, and by extension that of East Asian countries, did not develop different building types according to function. Palace complexes, religious complexes, and residential structures all had the same modular spatial units, with a more or less identical wooden construction method, and tiled roofs. But this did not mean architectural uniformity. Moreover, layouts of component building differed according to function. Also, subtle differences – such as the number and arrangement of modules, and details of the wooden parts of the frame – distinguished different types of spaces.

Figure 1.3. Comparison between Sungkyunkwan (left) and residences of elite literati named Yun Jeung (right) shows that both structures shared the same construction method and module system.

Hansong’s population grew steadily throughout the five centuries of the Chosun dynasty except during the time of the Japanese invasion at the end of the sixteenth century. After the invasion, much effort was put into reconstructing destroyed palaces, houses, and some Buddhist temples. The city gradually recovered its role as the capital and prospered throughout the remainder of the Chosun dynasty. In the eighteenth century, the implementation of daedong-bŏp, a revised tax law which unified forms of tax payment into one product, rice, encouraged trading (Kim, D.W., 2011). Commercial activities spread outside Jongro Street, and the existing sijon (official markets) were extended to the edge of Hansong. Sijon was extended to Cheonggye Stream area, and the unofficial market thrived outside the city gates, including the area outside Dongdaemun (Eastern Gate) and Namdaemun (Southern Gate). Trading and commercial activities sprung up in Yongsan and Mapo as well. In the late eighteenth century, as the residential areas outside the city gates developed, previously excluded areas were reincorporated into the administrative system (figure 1.4). Despite much destruction after the Japanese invasions in 1592 and 1597 CE, the recovering economy generated increased trading and agricultural output. In the latter period of the Chosun dynasty, some houses of rich commoners became large enough to compete with those of yangban. Literati, on the other hand, were divided into several factions, and factional rivalries often resulted in the purging of oppositional forces by removing them from high governmental positions. Some literati settled in rural towns, either permanently or temporarily, in order to gather local resources and strengthen their political support.

Figure 1.4. Boundary of Hansong in the late eighteenth century as seen in Gyongdo, showing that the city has expanded beyond the four gates originally demarcating the administrative boundary.

Some notable buildings constructed after the Japanese invasion are the Indeok Palace Complex and the Gyeongdeok Palace Complex. Although both of these palace complexes are gone now, they comprised a very important group of structures near Gyeongbok Palace Complex, the main palace complex. The new Changdeok Palace had a freer layout compared to Gyeongbok Palace, and halls were placed according to the natural landscape of the site rather than following an imaginary axis. During the latter half of the Chosun Dynasty, many ancestral shrines, called sadang, for royal families were built inside the capital.3 Since many auxiliary rooms were required for the storage of utensils associated with ancestral rites, these shrines occupied a large parcel of land. At the same time, shrines were surrounded by wall enclosures that prohibited random visits or staring passers-by. Thus, some scholars consider the construction of many ancestral shrines in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as adding a solemn and stagnant urban character (Kim, D.W., 2011).

At the same time, fortifying the city walls had become another important task, as a series of foreign invasions in the late Chosun Dynasty led to a widespread feeling of insecurity among the residents. During King Sukjong ‘s reign (1674–1720), destroyed parts of city wall were repaired, and a new city wall near Bukhan Mountain was constructed. Along with the new wall, military posts in charge of guarding the city wall were reorganized. The fortification of the existing city wall, and the construction of a new wall signified the will of the state to defend the capital in the event of military attacks by foreign powers. Along with commercial and economic developments, increased cultural exchanges between the Chosun Dynasty and neighbouring countries brought new intellectual trends. A group of Korean scholars, who learned about Western thought through exchanges with Chinese scholars, initiated the silhak movement, which emphasized the practical application of knowledge. Invention and the use of pulleys in large construction projects, such as the Suwon Hwasong City Wall in 1796, show the influence of a new school that favoured practical interests over metaphysical discussions.