![]()

Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth

Fort Worth, Texas

Tadao Ando Architect & Associates

2002

Figure 1.1 North facade and reflecting pool

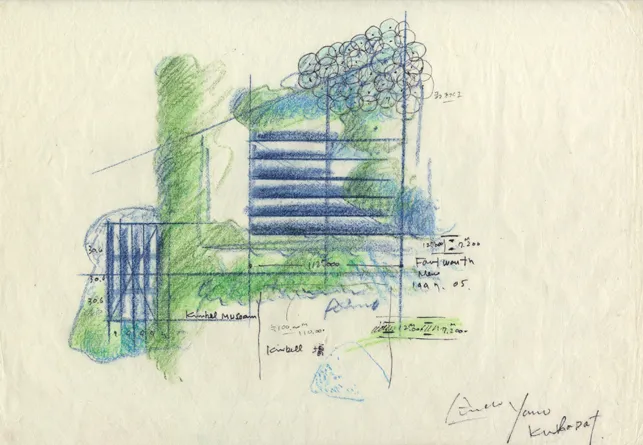

Figure 1.2 Sketch by Tadao Ando

Completely by coincidence, I made first visits to both the Guggenheim Bilbao and the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth on the day after Christmas, shortly after the buildings were completed. Though the two museums opened five years apart (October 1997 for the Guggenheim and December 2002 for the Modern) and are obviously very different architecturally, the atmosphere was surprisingly similar. The buildings were packed with locals and visitors from far away, art-lovers, architects, and the curious. The atmosphere was festive after the holiday and the public was marveled. The architecture was on display as much as the works of art, and the buildings were explored, caressed, and photographed. The visitors in Fort Worth seemed as fascinated by the vast 6,070 m2 (square meter; 1.5 acre) reflecting pond and the much-discussed concrete walls of Ando’s building (Fig 1.1) as the Bilbao public was by Gehry’s exuberant forms and titanium cladding. Ando’s characteristic elements are once again employed at the Modern: concrete walls, the reflecting pond, circular or oval forms. His ongoing desire to create a contemplative architecture is not incompatible with a desire to attract visitors, and the Fort Worth Modern again proves that the museum, regardless of the architectural style, is the great public building type of our time.

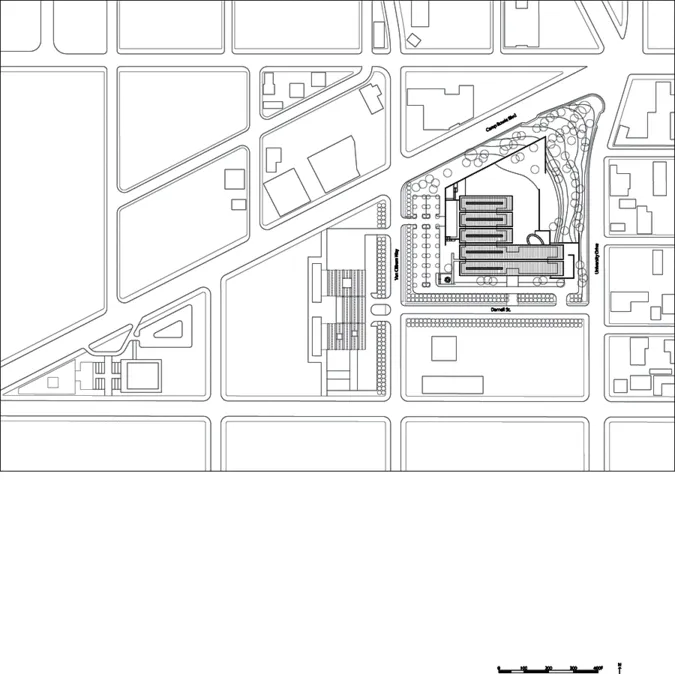

It is said that the American West begins in Fort Worth. Since the completion of Louis Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum in 1972, this venerated architectural monument has made Fort Worth a pilgrimage site for architects from around the world. Any project for the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth inevitably had to take into consideration the fact that the Kimbell is just across the street (Fig 1.2).

A work in the Modern’s collection entitled The Blind # 19 by the artist Sophie Calle is composed of three frames. One frame contains a frontal portrait of a young woman wearing sunglasses (we assume she is blind). A second frame contains a photograph of the back of a young man reclining on a sunlit bed wearing only boxer shorts. A third frame contains a text:

The man I live with is the most beautiful thing I know. Even though he could be a few inches taller. I’ve never come across absolute perfection. I prefer well-built men. It’s a question of size and shape. Facial features don’t mean much to me. What pleases me aesthetically is a man’s body, slim and muscular.

Ando’s work, likewise, aspires to see beyond the simply visual and engage all of the senses through the interactions of “muscular” materials such as concrete and granite and the immaterial: light, sky, wind, and sound. In Fort Worth, Ando intertwines art, architecture, and nature. Much of the interest of his buildings comes from the fundamental and essential constructional parts, from refined proportions, volumes, and forms. Ando speaks of “approaching the space of the cosmos” through his buildings, and because of his express search for the metaphysical in architecture, his work might be held to a higher level of achievement for how it carries this quest to term. The Modern is a beautiful building, visually and experientially, even if it is not perfect.

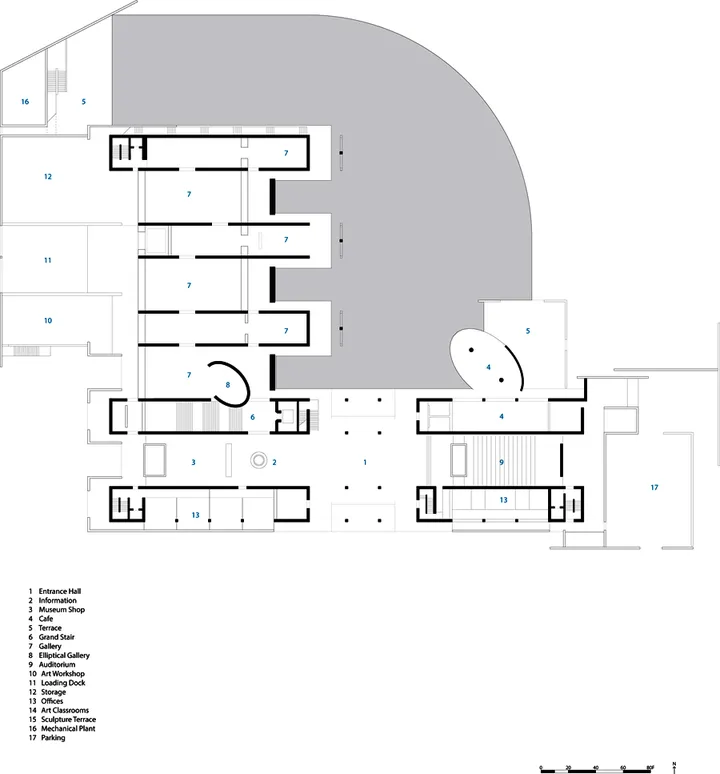

As in many recent museums, Ando has devoted a substantial amount of space to the entry and circulation (Fig 1.11). Arriving visitors gaze through the glass-enclosed, double-height lobby to the reflecting pond and the garden beyond. On the ground floor (Fig 1.4) to the east of the lobby are a 250 seat auditorium and a corridor leading to the museum cafe which is defined by a 22.85 by 15.25 m (75 by 50 ft) elliptical roof slab that is held up by only two 90 cm (36 in.) diameter columns. Administrative offices are on the second floor above the auditorium. On the west side are ticket sales, the museum store, restrooms, and the passage to the galleries. A concrete bridge with glass handrails traverses the lobby space to link the second floor level of the two sides. After passing ticket control a grand stairway (Fig 1.12) and elevators lead to the second floor galleries. Farther ahead the outside curve of the 11.25 by 7.30 m (37 by 24 ft) elliptical gallery (Fig 1.13) guides visitors toward the ground floor galleries. Other offices and support spaces line the south facade on both floors. The building is 14,214 m2 (153,000 ft2; square foot) with 4,924 m2 (53,000 ft2) of gallery space.

The Modern’s basement level houses separate art storage for photos, works on paper, and paintings with appropriate climate control for each. Boilers, chillers, air handlers, a backup generator and general storage are also located in the basement. An “L” shaped service corridor provides access to all spaces and borders a large mechanical area known as the “pit,” a crawl space where the ductwork originates. From the pit, ducts enter into wall cavities to make their way to the first and second floors. Large trucks can enter inside the delivery area at ground level. Storage and a workshop are nearby, and an adjacent freight elevator links all floors. Concrete garden walls enclose a mechanical yard at the north/west corner of the building that contains the cooling towers as well as the mechanical equipment for the reflecting pond.

The Modern’s galleries remain a powerful and memorable part of the experience of the building. They are simple, well-proportioned, white spaces that are strong but not in competition with the works of art. Multiple circulation paths give an impression of promenade and discovery rather than a predetermined exhibition itinerary. There are numerous places where visitors can step out of the exhibit, take a short break, and gaze at the landscape, the downtown skyline, or the sculpture garden. A dramatic linear stair that climbs the north side of the building links the upper and lower galleries and assures the continuity of the visit without backtracking (Fig 1.16).

Figure 1.4 First (ground) floor plan

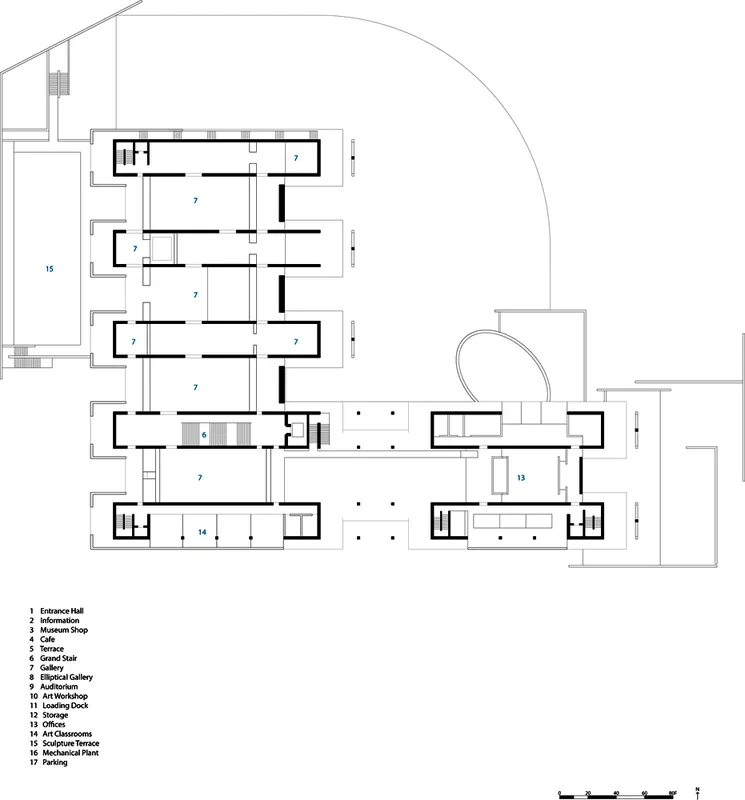

Figure 1.5 Second floor plan

On the ground floor the labyrinth-like spaces between the concrete walls and the exterior glass walls are playful. The close spacing and the large size of the mullions compromise the impression of transparency of the facade, however. The aluminum mullions spaced every 1.5 m (5 ft) are 20 cm (8 in.) deep with the glass placed in the middle. They are reinforced by 20 cm (8 in.) wide-flange steel columns. The glass panels are 3.65 m (12 ft) high between horizontal mullions. Floor grills for air conditioning are integrated at the base of the facade. Small louvers at the top of the glass facade contain services such as sprinkler piping and motorized shades. These louvers also contribute to the heaviness of the facade.

Three double-height exhibition spaces are interesting architecturally, yet it is not obvious what the intended relationship is between the gallery spaces they link vertically (Fig 1.14). The first floor galleries have stone floors. Light tracks spaced every 1.5 m (5 ft) are recessed into the 4.60 m (15 ft) high gyp board ceiling. The second floor galleries have white oak floors and the natural top lighting is of two types: continuous, gabled skylights combined with suspended translucent ceiling panels in the 7.30 m (24 ft) wide galleries and 60 cm (2 ft) tall linear clerestory windows with an integrated exterior louver system in the 12.20 m (40 ft) wide galleries (Fig 1.15). The 7.30 m (24 ft) wide galleries have a ceiling height of 5.00 m (16 ft 4 in.), while the ceiling height of the 12.2 m (40 ft) wide galley is 4.30 m (14 ft). In both cases the light is homogenous and somewhat lifeless. The translucent ceiling panels offer little hint of the outside sky and light conditions, or the structure above. Generally, visitors are left with the unfortunate impression of artificially lit gallery spaces.

During my visit on December 26, I spoke to one of the many fellow visitors w...