![]()

PART I

From Prehistory to History

![]()

Chapter 1

THE PREHISTORY OF THE TIBETAN PLATEAU TO THE SEVENTH CENTURY A.D.

Mark Aldenderfer and Zhang Yinong

At a conservative guess, the area that we today refer to as the Tibetan cultural region was inhabited by humans around 20,000 years ago; farming settlements were present at least 5,000 years ago. Tibetan history therefore could be said to begin almost 19,000 years before contemporary historians typically pick up the story. But that story is not simple; Aldenderfer and Zhang recognize the politically loaded nature of archaeological and genetic research on the Tibetan Plateau, and they correctly point out that “making explicit correlations between languages, ‘races’ or ethnic groups, and archaeological cultures is fraught with difficulty.” Nevertheless, their work presents the existing evidence on early humans on the Tibetan Plateau as well as the most plausible theories for the origins of these humans. This first article in the Reader very appropriately begins with an introduction to the region of Tibet, starting with the entire plateau. The region is massive; if the plateau’s quarter of a million square kilometers represented a country’s borders rather than just a geographic zone, this country would be the eleventh largest on earth. Moreover, the plateau’s average altitude of over 5,000 meters makes Tibet, on average, higher than the highest peak in the lower 48 United States (California’s Mount Whitney at 14,494’). This essay’s survey of the plateau’s terrain, major river systems, climate, and ecology provides an excellent orientation to the Tibetan cultural region. However, the focus of the essay is the prehistoric evidence for human habitation on the Tibetan Plateau.

THE POLITICAL AND ACADEMIC STRUCTURE OF ARCHAEOLOGY IN CHINA AND TIBET

For the sake of a general understanding of the archaeology of the Tibetan plateau in China and particularly the terms and usage in this article, it is necessary to make clear some possible confusions of the use of the term “Tibet” as well as in the nomenclature and organization of the administrative system for cultural resources in contemporary Tibet, which is currently based on Chinese ideology.

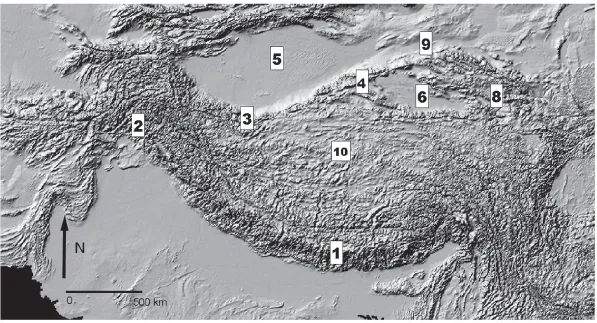

Contemporary Tibet is often vaguely referred to by scholars in different disciplines in terms of its geographical, ethnographic, and political meanings due to the complexity of its historical and current situations. The highest plateau on the earth, the Tibetan plateau, covers more than 2,500,000 square kilometers of plateaus and mountains in central Asia (fig. 1.1). Before 1950, “premodern Tibet,” as Samuel calls it,1 was constituted mainly by three Tibetan regions—central Tibet, Kham (eastern Tibet), and Amdo (northeastern Tibet)—and small population centers in the neighboring countries of Nepal, Bhutan, and India (including much of what is Ladakh and Sikkim today). After its annexation by China in 1950 and following the exile of the Dalai Lama in 1959, the major body of “premodern Tibet” in China was completely separated from that of Tibetan peoples in other Himalayan countries. According to Tibetologist Melvyn Goldstein, the concept of modern Tibet has a twofold meaning: “political Tibet”—a region that used to be ruled by the Dalai Lama and is currently named the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) within the Chinese governmental nomenclature, and “ethnographic Tibet”—a much larger area inhabited by all ethnic Tibetan people that covers not only a major part in China but also many regions along the Himalayas in India, Nepal, and Bhutan.2 While Tibet is still in many areas referred to by some scholars by its former integrity and traditional division, it has been reorganized and fragmented into several parts in China. These parts eventually fell into five contemporary Chinese provinces, including the TAR, Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan, and Yunnan (fig. 1.1). With the exception of the TAR, Tibetan territory and population only constitute a small part in each of the other four Chinese provinces.3

Figure 1.1

The Tibetan plateau, showing political boundaries, major rivers, and the extent of “ethnographic” Tibet. Scale approximate.

MODERN ECOLOGY AND PALEOENVIRONMENTS

The Tibetan plateau is the highest in the world with an average elevation of over 5000 meters (fig. 1.2). This oft-cited figure, however, obscures its extraordinary topographic and ecological variability. Some of the highest peaks on the planet, barren of life, are juxtaposed to deep valleys that have unique ecologies which have only been explored in the modern era. In this section of the paper, we describe briefly the topographic features of the plateau, its hydrology, climate patterns, and ecological and biome structure. Following this, paleoenvironments are discussed.

Figure 1.2

Major topographic features of the Tibetan plateau. 1: Himalayas; 2: Karakorams and Pamirs; 3: Kunlun Shan; 4: Arjin Shan; 5: Taklamakan Desert; 6: Qaidam Basin; 7: Qilian Shan; 8: Qinghai Hu (Lake Koko Nor); 9: Hexi (Gansu) corridor; 10: Jangtang. Scale approximate.

Before examining the plateau in detail, it is useful to review the fundamental structuring factors of high mountain and high plateau environments. As I have argued elsewhere, on the basis of the work of many geographers and ecologists, these environments are characterized by environmental heterogeneity, extremeness, low predictability, low primary productivity, and high instability and fragility.4 Highly dissected topography, combined with altitudinal effects, creates a patchy mosaic of juxtaposed microenvironments with varied spatial and temporal extents. Extremeness (high absolute elevations, very low temperatures, etc.) exacerbates this variability. Low predictability is the degree to which key environmental features have a predictable periodicity. High mountains and plateaus are usually characterized by low predictability. Low primary productivity is typical of high plateaus and mountains since they tend to be quite cold and depending on location, often quite dry. Finally, these environments are highly unstable, with significant risk of hazard such as massive erosion and damaging seismic activity. Resource patches are frequently destroyed though these events.

On the basis of these criteria, the Tibetan plateau is among the most extreme and difficult highland environments on the planet. It is fundamentally a cold, alpine environment where the average temperature in the warmest month is not more than 10ºC, and only three portions of the plateau—the Yarlung Tsangpo, Senggé Khebap, and Langchen Khebap river valleys, are not alpine by this definition. Since the plateau mostly lies between 30 and 35ºN latitude, seasonal climatic variation is strong, with a moderately long winter and relatively short summer, both of which are in great part contingent upon altitudinal zonation. Unlike many tropical high mountain and plateau regions, this strong seasonal variability on the Tibetan plateau improves the predictability of precipitation to an extent.

TOPOGRAPHY

The plateau, created largely by the collision of the northward drift of what was to become the Indian subcontinent and the land mass of what was to become Asia some 40–50 million years ago, apparently reached its modern elevation by at least 8 million years ago, and probably substantially earlier.5 The Himalayas, the highest mountain range in the world and which stretches in a vast arc along the southern margin of the plateau, were created in this ancient collision. The western and northwestern margins of the plateau are formed by the Karakorams and the Pamirs, which are almost as high as the Himalayas. Although these ranges are cut through by a number of large rivers, and can be traversed over very high mountain passes, the combination of high elevation and extreme topographic ruggedness make access to the southern and western regions of the plateau from these directions quite difficult. The northwestern boundary of the plateau is marked by the somewhat lower Kunlun Shan, which transitions into the Arjin Shan along the north-central margins of the plateau. The northeastern margin of the plateau is defined by a series of relatively low, parallel mountain ranges, with the Qilian Shan the northernmost of these. In general, these northern ranges are much lower than those to the south and west, and do not present as much difficulty for transit. However, as will be shown below, other topographic factors make this region a harsh environment. Finally, the eastern boundary of the plateau is marked by a series of northwest-southeast trending ranges created by major rivers that descend from the interior of the plateau into north-central China as well as southeast Asia. These valley systems are very deep and narrow, and rise precipitously toward the plateau. The extreme northeastern corner of the plateau contains the so-called Hexi (or Gansu) Corridor, where the Machu (Huang He or Yellow) River valley cuts through the mountains, and which affords relatively easy access to the interior of the plateau from the steppelands to the north.

The interior of the plateau is divided by other, smaller mountain ranges that generally run east-west. These ranges define four other major topographic features: the long, relatively narrow Yarlung Tsangpo valley in southern Tibet, the large, arid Jangtang rangeland that dominates most of the interior of the plateau, the Qaidam Basin, and the Qinghai Hu Basin, both located in the northeastern corner of the plateau.

The Yarlung Tsangpo valley and that of its major tributary drainage the Kyichu, as well as those of numerous smaller rivers, form the modern agricultural heartland of the plateau. Elevations of the relatively flat valley floors range from 3700 to 3900 meters above sea level. The valley is arid to the west, and gradually becomes wetter toward the east. The gradient of the river is gentle, and except in deep gorges, the river and its tributaries tend to form broad, shallow, braided channels.

Surrounding these valleys are low foothills and sometimes very steep mountainsides. The Yarlung Tsangpo courses through a very narrow gorge between the two ma...