![]()

1

Preparing for Entering Academia

The Hard Truth About the Academic Life

Getting a Head Start as an Undergraduate Volunteer

The Undergraduate CV

Finding Your Research Interests

Summary

The Hard Truth About the Academic Life

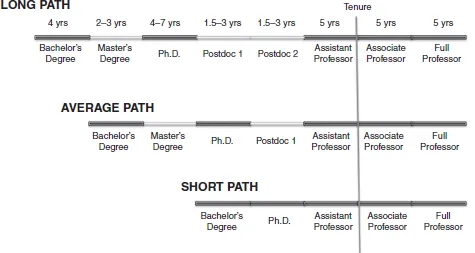

Choosing the academic life is not an easy choice to make. But, if you feel it is the right choice for you and you are a hard, smart worker, then it can lead to a permanent position in a job that is intellectually fulfilling, stable, and rewarding. The hurdles to obtaining an academic research job (a professorship or equivalent) include getting the following: a bachelor's degree, research experience, possibly a master's degree, a doctoral degree (Ph.D.), maybe 2–5 years of postdoctoral research experience, an academic job (e.g., assistant professorship), and tenure (Figure 1.1).

You might be able to skip a few of these steps; perhaps you won't need a master's degree or a second postdoc, but there are still many hurdles that you will need to overcome to achieve your goal. Luckily these “hurdles” are what trains you to be an independent researcher and thinker, and that training can be among the most fulfilling and worthwhile experiences in your life. There is no real “typical path”; every individual's experience will be different. Academia is fun; you basically get to do what interests you, discover new things, and interact with other people who are also having fun learning about things they are interested in. It isn't always a bed of roses, of course, but compared with some other ways of making a living, it is a great gig. One academic I know always replies to the question “How's your job?” with “Beats workin'.”

The academic life has a lot of perks and can be very fulfilling, but it might not make you rich. Starting annual salaries range from $40K to $80K, and most never make it much past the $100K mark. However, there is a great deal of job stability, and—best of all—if you succeed, you can make a living doing something you enjoy. Academia is extremely fulfilling to those who find satisfaction in solving problems in a particular area of research. Researching subjects that interest you, teaching what you know best, and, for the most part, making your own schedule are among the freedoms that research academics have that few others can claim. You can work 9 to 5 if you like, or 5 to 9. Nobody will be looking over your shoulder, telling you what to do; you must be your own nagging boss. Your ambitions have to match your academic goals; without this motivation, you will undoubtedly fail. You will receive very few pats on the back in academia; the only way you know you are doing a good job is if you notice that fewer people are complaining. Be warned, academia is not for the faint of heart. You will submit papers and grant proposals that you think are the best things since sliced bread, and you will be shocked by reviewers and advisors who will knock you down as low as you can possibly feel. The rewards of success are great, but only because academic success (e.g., discovering a new species, falsifying a long-standing hypothesis, etc.) goes hand in hand with your happiness. If you don't get excited about going to work for science, then science will make it very hard for you to succeed.

The people who I see achieving the most success are not necessarily the smartest, but they are almost always the hardest working. You might want to go to graduate school in order to become a lecturer at a small liberal arts college with no research component, but you will still have to play the game with those students getting doctoral degrees in order to land research positions at top universities; you won't be treated differently just because you have different goals and ambitions.

Academia is all about self-motivation, but one great incentive is tenure. (Tenured professors are those who have their positions guaranteed [i.e., they can't be fired unless they do something prohibited or illegal]; assistant professors are essentially on probation.) Tenure gives you nearly complete academic freedom. Getting tenure means you have made it through the academic ringer and that your institution wants to keep you forever. You will only be granted tenure once the institution is sure that you are self-motivated enough to keep working hard, if not for them, for your own sake. If for no other reason, your work should keep your interest; as the old adage goes, “If you love your job, you never have to work a day in your life.”

Getting a Head Start as an Undergraduate Volunteer

It is never too early to start building up your resume by getting research experience. Research experience is something you most certainly need to distinguish yourself among the hoards of undergraduates whose only experience is classwork. This experience will also tell you how much you like research, and the more research you do, the more fun and interesting the research you are offered becomes. If you volunteer to work for an academic, you might start by doing menial jobs, like washing lab equipment or filling boxes with neatly arranged pipette tips. Once you've proven to be someone who can be trusted to arrive on time and not break things, you may then be asked to do something more exciting, like mixing and preparing chemicals or taking x-rays. This kind of menial experience is actually a good start. Begin creating your CV and adding things like the following:

Volunteer—Wainwright lab, University of California Davis. Made x-rays of fishes for studies on the ecological morphology of darters (Etheostomatinae). Fall 2011

This might sound obscure, but someone looking at your CV might know Peter Wainwright, or they may need someone who knows how to make x-rays, or who is interested in darters. You want to provide as much information as you can in just a few lines (see more about your CV below).

You might not be the only volunteer in the lab; you might see that other volunteers are doing things you wish you were doing instead: Be patient, your time will come. People who work hard, learn quickly, and are inquisitive are almost always offered more opportunities. Whiners, complainers, latecomers, and the generally unenthused are quickly shuffled out the door.

You might not work directly with the PI (principal investigator, or head of the lab); more often you will work for a graduate student or postdoctoral fellow. You might even end up getting paid for your work, which is great. More important than the money, though, if you can believe it, is the experience. The ultimate prize is to be included as an author of a publication. A research publication with your name on it means you have just joined the ranks of researchers. People who Google you (or better yet, Google Scholar you) will find your paper and be impressed, and you will have an entry in the most important category of your academic CV—Publications. Before you get to that point, however, and maybe before you even get to work on a real project, you might have to wash 1,000 dirty beakers in a sink for 8 hours a week for 3 months.

If you volunteer and are excited about working in a lab or on a research project, that's great. It is okay to be happy, gregarious, and inquisitive. There is a fine line, however, between being outgoing and being annoying. If you are working with someone who is writing a manuscript on the computer in the other room, don't just barge in and start chatting them up about the party you went to last night. Academics are busy people with a lot on their plates, and they typically have short periods of time in which they need to concentrate fully on a particular task. Breaking their concentration with a myriad of questions will not go over well, but having all of your questions answered in one shot is better than interrupting someone five times in 1 hour. Try to gauge your advisor's reactions to your questions to see whether he is becoming frustrated. It might not be your fault if he is upset, but it can quickly become your fault. The best volunteers are problem solvers and note takers who understand their roles and who want to move up in the world and know how to get there.

Try to solve problems yourself but not at the expense of making a mistake that could end up costing a researcher even more of his precious time. If the PI keeps his door closed, it is probably closed for a reason. But, an emergency is an emergency, and if you have a question that can stave off an emergency you better ask it—closed door or not. However, if there is a graduate student or technician you can ask instead, you probably should. As with any job, fitting into the group's social dynamics is almost as important as the work itself. Remember that, as a volunteer, you are on the lowest rung of the totem pole. That doesn't mean you should be mistreated, but it does mean you may not have as much access to the PI's time as you would like.

Aside from being including in a publication, the other thing that can be more valuable to you than money is a nice recommendation letter. Your professors or lecturers might write you recommendation letters for graduate school because you got an “A” in their classes, but these are typically informal letters that they write dozens of every semester. They might do little more than replace the name of the last “A” student who asked for a recommendation letter with yours. (You'd be surprised how many letters I've read where the gender of the student is incorrect throughout the recommendation, because the author didn't bother changing the gender along with the name.) If you work for someone as a volunteer for a couple of months, you should most certainly ask for a recommendation. Even if you worked most closely with a graduate student or a postdoc, you should ask them to write a letter that is signed by the PI as well. The person who wrote the recommendation letter, in most cases, carries more weight than the actual content of the letter. If you get a recommendation letter from E.O. Wilson or Stephen Hawking, it won't matter if it is two sentences long; it is still better than a 15-page letter written by your graduate student TA (teaching assistant) who only knows you from class.

The Undergraduate CV

The CV is your curriculum vitae, from the Latin for “course of life.” It is your introduction to all who you will meet for whom you want to work and impress. If you send someone an e-mail about wanting to work for them, the first thing they will do is look you up on the Internet. If your Facebook profile is a picture of you drunk and naked at a frat party, then your correspondence with that person will likely not go any further than your introduction. Aside from being diligent about your social media profiles, you should also write a professional CV that you would use in corresponding with academics.

As an undergraduate, you are not likely to have a 15-page CV, but that's okay. The important things you need to showcase are your skills, who you've worked for, and your other relevant experience. See Appendix 1 for an example of an undergraduate CV.

Finding Your Research Interests

Perhaps you might only have a vague idea of what you are interested in—that's okay. If you know you like quantum mechanics and you admire Schrödinger, at least that's a start. It is okay to have only a broad interest at first. Don't think about your interests in terms of what jobs are out there or how much money you'll make; instead, think only of spending your life studying something that you are interested in. Over the course of your undergraduate career, you met interesting professors and learned about interesting things from your textbooks and friends. Certainly some area of research piqued your interest; otherwise, you wouldn't be reading this book. Perhaps you were listening to a lecture in a natural history class and thought, “You mean they still haven't figured out how orcas communicate in a hunt?” If you want to find out more, there is of course the library and the Internet. But- to find out what really is going on you need to start reading the primary literature, that is, science journal articles. Learn how to use Google Scholar (http://www.scholar.google.com), where you can type in a subject or a researcher's name to find available articles. Also learn how to use the ISI Web of Knowledge, or Scopus, which are the grown-up versions of Google Scholar. If you don't know how to use these or don't have access to them, ask a professor, librarian, or graduate student who does. Once you've found articles that interest you, look up more papers from the citations in the Literature Cited or look up more papers by the same authors. If you find yourself looking up work by the same authors, you might want to contact those authors as potential future advisors. Just as with food, only you know what you like. Discovering what you like most will mean sampling lots of things. If you want a career in science, you will have to read a lot. The more you read, the more you'll understand and the better prepared you'll be for the next step. The earlier you know what you like the most, the quicker you can get started on focusing on learning all there is to know on that subject.

Summary

- Although the academic life may not be the most glamorous, and it won't make you rich, it can be incredibly fulfilling.

- Self-motivation is the key to academic success. Because few people will give you encouragement, you will have to really want to accomplish your academic goals because you are genuinely interested in discovery and learning.

- Being a tenured academic is a sweet deal, and few other jobs offer the same kind of flexibility and stability.

- Moving up the academic ladder will mean that you have to leave the ground. Start by volunteering in labs that you admire, and begin building a set of skills and an array of experiences that will help you gain more research experience

- As you gain experience, start creating a CV that you can use as your “introduction” when contacting academic professionals.

- Get recommendation letters from established PIs rather than from PI's graduate students or postdocs.

- Read scientific articles that interest you to narrow your focus on the research that most interests you.

![]()

2

Applying for Graduate School

The Hard Truth About Applying to G...