![]()

1

Interface

In the field of human-computer interaction (HCI), the word interface refers to the physical or graphical means by which a user interacts with an information system. In current architectural practice, computer interfaces have transcended traditional command-based graphical screen displays and are forcefully beginning to integrate directly with built environments. Inevitably, as this trajectory continues and integration widens in scope, interfaces will assume ever more explicit and expansive spatial dimensions, and information systems will take on increasingly influential roles in buildings. In this view, the concepts of interface and architecture blur: built environments become “smart” and responsive; performance data, gathered in real time, dynamically adjusts building components and system operations; processors learn patterns of behavior, enabling them to propose and implement meaningful environmental changes. Given this context, it is obvious that blurring the built environment with information technology promises new directions for architectural practice: architects find themselves increasingly responsible for designing information systems as well as buildings. Users of building information modeling (BIM) software are already aware of the relationships between their work and the information systems involved in the management and operation of the completed building. Interfaces, in their expanded role within the built environment, are no longer simply concerned with “users” and information systems: they now enable multiplicities of factors, constituencies, forces, movements, and influences to interact with, mutually reinforce, or contaminate each other.

And yet, the conflation of interface and architecture can be misleading. Just because the traditional concepts are beginning to blur does not mean that every interface is architectural nor that every instance of architecture is an interface.1 Certainly, like any other interface, a specifically architectural interface must make it possible for multiple views and constituencies to interact. In other words, it must be cohabited by multiplicities. But something more than the mere possibility of interaction is required to establish an architectural interface. Architectural interfaces enable a special kind of interaction, one that problematizes its own presence. This means that an architectural interface cannot be transparent, an empty field or a tabula rasa, but instead must be more like a mesh or filter, a thickness affecting the perception of anything passing through it.2 And furthermore, by turning itself into a problem, the interface makes it possible to assess and negotiate competing priorities. In short, the architectural interface must establish conditions for apprehending differences.3

A window in a building’s wall is an apparently trivial example of an architectural interface. A window makes it possible to apprehend differences between otherwise distinct conditions (i.e., between the room and the exterior, or between the condition of being enclosed and the condition of being in the open); it makes possible a kind of interchange between them. But geometry alone fails to fully account for the specificity of the window as an architectural interface. Colomina, in discussing the fenetre en longueur (i.e., the long or horizontal window), suggests that the window—indeed architecture considered generally—problematizes representation as the reproduction of objective reality, making concepts thinkable.4 In a related way, de Certeau’s well-known discussion of the World Trade Center highlights the significance of distinct vantage points from which to view and apprehend the world, and through which architecture establishes a meaningful difference in perception (i.e., between the street and the observation deck), and more critically, distinguishes between distinct patterns of human behavior and thought.5

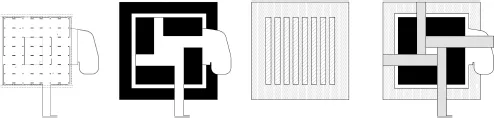

But architectural interfaces are not limited to physical constructions such as towers, windows, or rooms. Representational artifacts such as architectural drawings, installations, and models are also capable of functioning as architectural interfaces. A set of drawings of the Government Museum and Art Gallery in Chandigarh, prepared in the manner of Bruno Zevi’s analysis of St. Peter’s (Figure 1.1), serves to test this idea: the drawings, through specific acts of omission or highlighting, make it possible to establish difference among ways of understanding the building’s physical form, and the limitations of the traditionally constituted floor plan in revealing or highlighting these differences, but at the same time they imply differences related to the practices of people experiencing the building.6

Books, too, like drawings or windows or rooms, set conditions in place making it possible for readers to establish meaningful differences: to project, on the basis of their own imagination, through the structure of writing, a possible future.

Figure 1.1 Government Museum and Art Gallery (Chandigarh, India).

Whatever else an architectural interface is understood to be, its function can never be as simple as one that an omniscient designer could predict or determine. This is because when people are confronted with an architectural interface (e.g., a window, or a set of floor plans), their patterns of thought—while certainly triggered or structured by what they encounter—are grounded in their own experience and memories; actions, behaviors, and performances are always idiosyncratic to a degree; and the possibility and significance of differences are visualized accordingly. To appropriate Barthes from a different context, the architectural interface brings “multiple writings, drawn from many cultures and entering into mutual relations of … contestation.”7 Demonstrating a parallel with the software interface, the architectural interface is the overlapped or shared space within which two or more conceptual frameworks come into conflict with the possibility of exchange, and the highlighting of potentials, capabilities, affordances, and possibilities. To restate the earlier formulation: the architectural interface is a site where difference is produced.

Representation, buildings, cities, exhibitions—in short, architecture—constitute the mechanism through which thought is organized and discourse is enabled. Some aspects of this exchange are inevitably facilitated while others are foreclosed or made more difficult. In this view, interface in architecture is neither a surface nor a point of contact, it is an inhabitable depth.8 It is not a display or a wearable device in and of itself, but rather the set of affordances made possible through the display or device. Most importantly, while in the context of software, interface implies or connotes frictionless communication across a surface or a boundary (e.g., via computer screens or home assistants), neither architecture nor its representation ever seems to achieve perfect transparency.

Thickness

Supposing, then, that the architectural interface provides a kind of structure— physical, metaphorical, conceptual—around and through which ideas can be exchanged and differences can be perceived and produced, it follows that the interface makes certain kinds of thought and act easy; some kinds of communication are facilitated, but all are contingent on the specificity of the interface itself. This means that while any given interface may promise unlimited freedom and openness concerning the ways people organize their thinking about the world, it is never quite that simple: interfaces always offer both avenues and constraints for thought, and the forms in which concepts are perceived and thinking is organized, though open-ended in some ways, are characteristically constrained. This is true in different ways for different kinds of interfaces: just as software applications are designed to suit specific purposes and omit others from consideration, buildings and drawings have the ability to highlight some aspects of architecture while pushing others to the background.

Invariably, the architectural interface, in failing to achieve perfect transparency, always implies a kind of thickness, referring literally to the measurable distance across which perception and exchange are enabled; or it can refer to direct density of material, impenetrable by degrees to vision or sensibility. Analogously to software interfaces, thickness can refer to the difficulty of using the interface to perform a certain task. Thick interfaces, in architecture, could be embodied within thick walls, but they could also appear in the form of sectional shifts in floors and ceilings. Thickness carries a metaphorical connotation of impermeability: interfaces are variously porous and opaque; they privilege certain modes of understanding over others; they cause a shift or rupture in what would otherwise be smooth—and in so doing, they force unique consciousness of possibilities. Expressed differently, architectural interfaces always bring about a pause, a slowing of time. Perhaps paradoxically, this constitutes their greatest value to the architectural discipline.

As a characteristic of architectural interface, thickness may result from the specifics of an architectural design. Rowe and Slutzky, in their seminal discussion of literal and phenomenal transparency, implicitly address thick interfaces in quoting Kepes; they support the assertion that architectural interfaces allow a kind of “simultaneous perception of different spatial location” and “fluctuating space.”9 Yet, the specifics of architectural design itself are only part of the story, as thickness is also a consequence of assumptions, practices, and behaviors in relation to design. Consider Aldo Rossi’s competition proposal for the Monument to the Resistance in Cuneo, an unbuilt work consisting of an apparently solid cube, hollowed to make room for a stairway leading upward from the base to a mid-height level open to the sky.

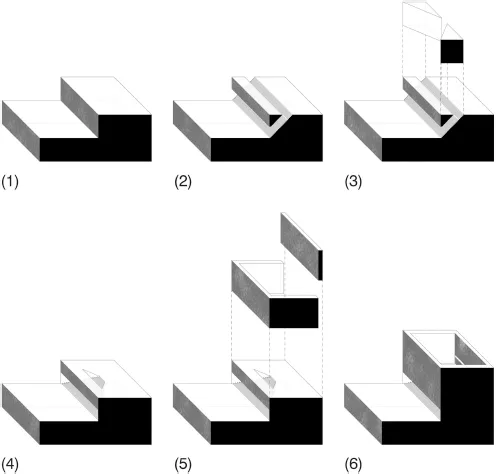

A set of elevation-oblique drawings sets forth a possible conceptual assembly of the design of the architectural interface at the Monument to the Resistance (Figure 1.2). The initial conceptual move, represented in diagram (1) in Figure 1.2, is to establish an architectural step at an urban scale, lifting a platform up above the street to a level significantly greater than an individual’s height. (Rossi’s proposal called for the platform to be at a height of approximately 6 meters above the ground.) This urban-scale step or platform is the fundamental move in establishing an architectural interface: subsequent moves seek to refine and focus the urban step to the scale and behavior of individuals visiting the site.

The next move in the conceptual assembly sequence, represented in diagram (2), introduces a human scale by establishing stairs at the street-side of the monument. Conceptually, the stairs can be understood as being “carved out” of the urban step, but significantly, a portion of the step is left in place above the stairs, so that visitors entering into the monument must pass beneath a wide lintel. Next, in diagrams (3) and (4), two masses triangular in plan are conceptually inserted at either side of the stairs, resulting in the stairs themselves becoming narrowed, so that an individual ascending the stairs moves progressively from a wide stair (at the bottom) to a narrow stair (at the top). Finally, in diagram (5), a set of walls is placed atop the elevated platform, blocking all views except for a view of the sky itself. The wall that visitors confront directly upon reaching the top of the stair is sliced horizontally, at a height permitting visitors to see through the slice and beyond to the spatially and temporally distant mountains.

Rossi’s monument establishes an architectural interface between ground and sky, between the familiarity and closeness of the street and the unfamiliarity, or memory, of the mountains. With Rossi’s work, simultaneity of perception is made possible but only after a separation; a shift from the space of the street, from its immediacy and cacophony, through a timeless passage into a highly constrained and yet open volume, one in which time is simultaneously about distant memory and the daily cycle of the sky. In short, the Monument to the Resistance is a thick interface because it works like a filter; it places constraints on visibility and sensory perception; it interposes itself between the street and the distant ridge, making it possible to characterize their meaningful differences. But in all of this, there is an important qualification: the Monument to the Resistance, being an unbuilt project, establishes an interface through drawings, not as something that can be bodily experienced.

Figure 1.2Conceptual sequence, Monument to the Resistance (Cuneo, Italy).

Perhaps paradoxically, a thick interface need not forcefully assert its presence; it can be something that exists at or near the edge of perception. Many religious structures work as thick interfaces in exactly this way. Spaces and zones within sacred precincts both recognize and enforce differences between laypeople and clergy; they determine the bounds of ritual; they establish differences that are profoundly significant to members of the congregation but that may be completely incomprehensible to outsiders. Failure to observe the differences or to abide by the implied expectations risks ostracization or persecution. Yet another kind of thick interface largely invisible to perception is the broad background of the everyday city—that environment that is ubiquitous and mundane, that which is so familiar that it is not considered remarkable. The invisibility of the everyday city, or its lack of distinction, does not diminish its power over behavior and thought.

By contrast, a thin interface is one in which the expected transmission of architectural thought or the communicative potential of space is explicitly defined.10 Lines on a highway separating lanes of traffic, or directiona...