![]()

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION: UNDERSTANDING THE CONTEXT OF CHANGE

THE GEOPOLITICS OF EASTERN EUROPE

Eastern Europe has long played a crucial role in modern European history and is destined to be the focus of some of the most far-reaching changes in global politics. It has had a stormy and eventful history. At no point in history has it been easy to define the region in any other than geographical terms. What constitutes Eastern Europe has varied with time, as have the forces operating within the area. For centuries, trends in Eastern Europe have served as a litmus test for the ebb and flow of the competition between Eastern and Western worlds. The complicated history of Eastern Europe is grounded in geography. The developments in Eastern Europe have been much influenced by its physical, economic and human geography. The distinctive geopolitics of Eastern Europe derive from the region’s perceived location on the borderlines between Europe and Asia. One important feature of the region’s spatial location is its comparative closeness to Asia. For centuries, Eastern Europe has been considered to constitute a ‘crush zone’ between Europe and the Eurasian heartland, and has been subjected to periodic waves of invasions [9; 23].

From a geographical point of view, one outstanding feature of the area is its mountainous character. Eastern Europe is cut in half by the Carpathian Mountains. Although the mountains contributed to particularism and isolation among the peoples, they did not provide a natural barrier against outside invasion. To the north, the eastward extension of the North European Plain has given invaders easy access from both directions. Another invasion route was found between the Carpathians and the Black Sea. No natural barriers hindered passage from the lands north of the Black Sea, along the Danube Valley, into the Pannonian Plain. In the Balkans, the main ridge of the Balkan mountains, stretching westward from Sofia to the east, cuts the peninsula into two [23].

Eastern Europe does not have any access to the open seas, although this has not necessarily impeded economic development. The region’s socio-economic development has been shaped by one major geographical feature, the River Danube. The Danube flows from Bavaria, through Austria, Slovakia, Hungary, Serbia and Romania to the Black Sea. The Danube and its tributaries played a vital role in the settlement and political evolution of Eastern Europe. Throughout history, this great river has been the principal route in this area for military invasion, trade and travel. Its banks, lined with castles and fortresses, formed the boundary between great empires, and its waters served as a vital commercial highway between nations. The Danube is of great economic importance to the countries that border it — Ukraine, Romania, Yugoslavia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Slovakia, Austria and Germany — all of which variously use the river for freight transport, the generation of hydroelectricity, industrial and residential water supplies, irrigation and fishing [24; 119] (see also Map 1 on p. x).

Eastern Europe has always been less developed than the countries further west. From the time of the Enlightenment, East Europeans have struggled to emancipate themselves from a legacy of underdevelopment and dependence. For most of its history, Eastern Europe has constituted part of the European economy’s periphery. Edward Tiryakian describes Eastern Europe as an historical and cultural area that forms a double periphery [41]. It has been, historically, a periphery of two more remote civilisations, that of Moscow and that of the Ottoman Empire. It has also been a periphery of more accessible Western civilisation. One result of this situation of structural dependency has been that Eastern Europe, for the greater part of the modern period, has lacked autonomy in the economic as well as in the political sphere [41].

Today most of Eastern Europe remains relatively backward, under-capitalised, under-productive and under-employed. Politics in Eastern Europe also reflects the region’s relative economic backwardness and more traditional social structure. Eastern Europe had not been greatly affected by the ideas of the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century. Nor did the liberal revolutions of the nineteenth century take root in the mostly rural societies of Eastern Europe. The political culture is, therefore, less developed than it is in Western Europe, and provides opportunities for demagogues and populists. Notions of consensus-building, tolerance and compromise politics are less widely accepted. Ideas associated with the classical liberal tradition are much weaker in Eastern Europe than in the West [23; 36].

A constant theme in the politics of Eastern Europe in the twentieth century has been the close linkage between domestic economic and political developments, social structures and culture on the one hand, and the external environment, that is changes in the wider global system, on the other. The linkage between domestic and international affairs has grown rapidly in both directions in the late twentieth century. There is a complex interdependence between the regional and the global, which provides us with an essential background for analysing the changing dynamics of international politics in this region. On the one hand, fast-changing domestic dynamics and new demands have become increasingly dependent upon international politics. On the other hand, the historical and cultural traditions of the East European states have remained important in determining the main focus of international affairs in the region [36; 69; 70].

Until relatively recent times, Eastern Europe did not exist as a distinct geographical or political notion. After the First World War the northern part and the southern part of Eastern Europe were united into a single geographical unit. After the Second World War the geographical notion of Eastern Europe merged with the ideological notion to form the contemporary political-geographical concept. For all practical purposes, Eastern Europe meant communist Europe, except for the USSR. It meant a group of countries sharing state socialist regimes and having antagonistic relations with the capitalist states in the West. Thus, geographical Eastern Europe and political Eastern Europe were not perfectly compatible. This definition excluded Greece, Turkish Thrace, Finland and the European non-Russian republics of the Soviet Union, which are geographically part of Eastern Europe, and included the German Democratic Republic and the former German provinces of Pomerania and Silesia (then parts of Poland), which traditionally were not considered to be part of the geographical Eastern Europe [33; 79].

Eastern Europe is a mosaic of peoples and cultures of very different origins and varied historical experience. It is only the experience of ‘communism’ between 1945 and 1989 that imposes a unity on the area. Communist Eastern Europe had a stormy and eventful history. Beginning in 1944, relations with Moscow were at first flexible. However, after a short-lived flirtation with ‘national roads to socialism’ from 1944 to 1948, a Stalinist assault took place from 1948 onwards. Stalin’s system of control over Eastern Europe encompassed the creation of command economies and centralised bureaucratic state apparatuses controlled by the Communist Party. From that point on, Soviet influence and the firm control of Moscow over the whole region remained the crucial fact of life until 1989, the historic year of geopolitical transition. It is this common communist experience that justifies the collective use of the term ‘Eastern Europe’ for societies whose pre-communist histories were very varied [66; 80].

Elements of history, culture and ideology combined after the Second World War to shape Soviet policy towards Eastern Europe. That policy has undergone many changes since that time, but it was always motivated by core Soviet interests, interests determined by geography as much as by ideology and power politics. The Soviet Union saw Eastern Europe as a buffer zone, a base and a laboratory: a military and ideological buffer zone against the West; a base for the protection of socialist power and Soviet influence over the rest of Europe; and a laboratory for the exoneration of Soviet ideological aspirations of internationalism and proletarian dictatorship. The relative weight reserved for these factors has of course changed over time, but the importance of the East European interstate system, and Moscow’s control over it, was central to the strategic thinking of the Soviet leadership [33; 49].

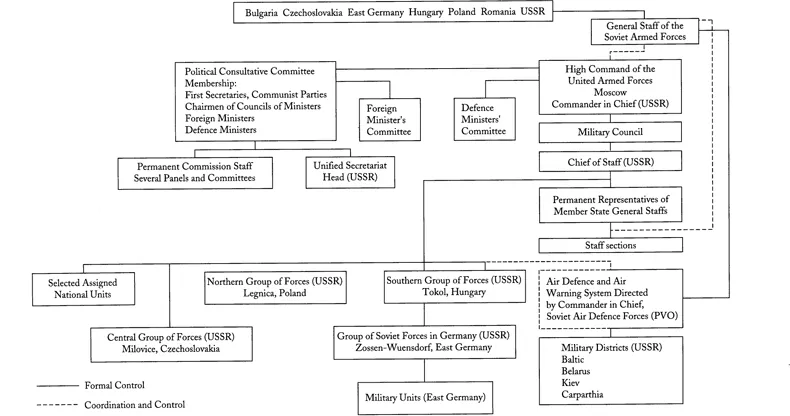

Ultimate control of Eastern Europe was exercised by Moscow against the backdrop of the threat of force. The military organisation uniting the Eastern European socialist countries under Moscow’s domination was the Warsaw Treaty Organisation (WTO), or Warsaw Pact as it is commonly known. The Warsaw Treaty was signed in Warsaw on 14 May 1955, by representatives of Albania, Bulgaria, Hungary, the German Democratic Republic, Poland, Romania, the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia. A combination of internal and external factors was at work at this early stage. However, the most immediate cause was the accession of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) to the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO). This is the event most frequently cited by Soviet commentators as the origins of the Warsaw Pact. The preamble to the Warsaw Treaty identified the reintegration of West Germany into the Western Bloc as giving rise to the need for a counter-balancing alliance. In some points of phrasing the Warsaw Treaty mirrored that of the North Atlantic Treaty of 1949, which established NATO. On the same day as the Warsaw Treaty was signed, an announcement was made on the formation of the Joint Armed Forces of the Warsaw Pact signatories. In effect, the signing of the Warsaw Treaty legitimised the presence of Soviet troops in Hungary and Romania, since they would otherwise have had to withdraw once Soviet forces withdrew from Austria with the signing of the Austrian State Treaty. The Warsaw Treaty therefore provided a broad legal basis for the stationing of Soviet troops in Eastern Europe [66; 81; 94]. Indeed, Molotov, then Foreign Minister of the Soviet Union, saw the Warsaw Pact primarily in terms of safeguarding the military security of the socialist camp.

Apart from the brief period of Hungarian withdrawal in 1956, only Albania withdrew, in 1962, from the Pact. No other state joined. The nature and extent of Soviet control in Eastern Europe was altered over time yet the Warsaw Pact continued to provide a complex mechanism for coordinating military and foreign policy for the Soviet bloc states, with the USSR being the ultimate arbiter [51] (see also Figure 1).

With the end of the Cold War, the reasons for the region’s continuing importance have radically changed. European politics have taken on a new meaning following the fall of the Berlin Wall. Eastern Europe has opened up at its Western side and is no longer the front line for an authoritarian superpower. Instead, it finds itself acting as a ‘buffer region’ between the European Union and Russia. Eastern European countries are now at the core of the process of integration across the Cold War European divide [74].

Figure 1 The structure of the Warsaw Pact,1976

Reprinted from Communist Regimes in Eastern Europe by Richard Estaar, with the permission of the publisher, Hoover Institution Press. Copyright © 1977 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University.

THE CONTROVERSIES OVER THE CAUSES OF COMMUNISM’S COLLAPSE IN EASTERN EUROPE

Much has been written on various aspects of East European history and some on the collapse of the communist regimes there. Most of the publications are, of course, monographs concerned with limited aspects of East European history and politics. But some general works provide useful background material and a general overview on the region.

Many reasons have been advanced for the collapse of communism. These can be summarised under two general categories: the first category is related to the inherent weaknesses and internal structures and developments of the communist system; the second is related to external factors and global developments. Some writers in the first category explain the collapse as an inevitable result of the inherent problems and internal mechanisms of the socialist state system. In this view, the evolution of communism contained within itself its own rejection [41]. These authors emphasise that a political system based on rigid single-party rule creates no real support. Repressive regimes, they say, are inherently vulnerable. Communist political systems in Eastern Europe collapsed at the end of the 1980s because of long-standing internal weaknesses that denied them the popular legitimacy needed for long-term survival. According to this view, the collapse was caused by dictatorship and popular demands for liberal-democratic rights. Eastern Europe rejected communism, it is contended by authors such as Wandycz, because it was contrary to freedom and because it was foreign [124]. Ralf Miliband, similarly, writes that it was the authoritarian nature of communism that must, above all, be sought as the reason for the regimes’ collapse, for the lack of democracy and civic freedom affected every aspect of life, from economic performance to ethnic strife [11]. Richard Pipes, in his book, Communism: The Vanished Specter, claims that communism collapsed because it contradicted human nature [83].

Other authors emphasise the failure of the economic system of the socialist states as the reason for collapse. In this view, the command economies of socialist states were increasingly incapable of providing labour incentives, efficient allocation of capital and stimulants to innovation. The collapse was, Philip Longworth asserts, above all a consequence of economic failure [70]. Change happened in Eastern Europe first, says Charles Gati, because all communist regimes there were dissatisfied with the performance of their economies [37]. To the authors in this group a serious dissatisfaction with the performance of East European economies is the key to understanding the historic changes of 1989 [44].

It has also been argued by some commentators that other internal factors played as big a role here as economics. Boris Kagarlitsky says psychological factors were equally important. The instability of communist social structures, the destruction of former institutions and the deep crisis that emerged as a result of disappearing traditional networks, all helped to make social psychology an important factor [58]. It has also been claimed that behind the collapse of the East European regimes lay their ‘moral hollowness’. This, according to Gale Stokes, made the role played by ideas particularly important. In this view, political ideas have an autonomous strength that is not necessarily rooted in social relations and economic development [108].

The communist parties, paradoxically, played an essential role in their own collapse. According to Poznanski, communist party leaders lacked belief in their own mission. During the 1970s and 1980s, party leaders stopped believing in what used to be perceived as the historic mission of the apparatus [84]. When the party lost its power to command the polity, says Robert Skidelsky, the system stopped working [72]. Ernest Gellner explains this as the major fai...