![]()

Part 1

Nineteenth Century—Origins, Imitation, Type

![]()

1

Towards an Inaugural Definition of Type

The actual causes of a thing’s origin and its eventual uses, the manner of its incorporation into a system of purposes, are worlds apart; that everything that exists, no matter what its origin, is periodically reinterpreted.

—Friedrich Nietzsche1

Chapter 1—List of Contents

Antecedents

The Little Rustic Hut

Quatremère de Quincy

Type as Origins, Classification, Imitation

Type Versus Model

Durand—Architecture as Taxonomy

The Précis—Towards a Design Methodology

Type as Diagram

Antecedents

The eighteenth century in Europe became known as the Enlightenment, a period characterized by dramatic changes in science, philosophy, society, and politics. The term “Enlightenment” was introduced by Immanuel Kant in his brief 1748 essay (“What Is Enlightenment?”),2 where he defined the concept as humankind’s new phase, defined by its capability of emerging from its “self-imposed immaturity. Immaturity is the inability to use one’s own understanding without another’s guidance.”3 Man, according to Kant, should be capable of thinking by himself, thus becoming liberated from traditions and institutions, such as the church or political and governmental structures. “This enlightenment,” he posits, “requires nothing but freedom—and the most innocent of all that may be called ‘freedom’: freedom to make public use of one’s reason in all matters.”4 The principal guiding principles of the new era, according to Kant, are science and philosophy.

Two fundamental issues marked the transformative developments in the sciences throughout the Enlightenment: the notions of classification and origins. With the publication of Systema Naturae (1735),5 Carolus Linnaeus became one of Europe’s leading scientists advancing the notion of classification in the biological sciences, developing a strategy that would be extremely influential in all areas of knowledge. Linnaeus proposed a division of living things into Classes, Orders, Genera, and Species,6 establishing a correlation between the species’ physical characteristics and their progeny, where each present form was the result of a prolonged evolutionary chain. The strategy was supplemented with a novel nomenclature criterion combining the names of the organism’s specie and its genus. Linnaeus’s ideas were very influential in all areas of knowledge; architecture was no exception. It became apparent that the built environment could be examined and analyzed according to similar taxonomic criterion. As posited by Anthony Vidler, “If Linnaeus was able to establish a classification of the zoological universe in Classes, Orders, and Genera (with their attendant species and varieties), why should not the architect similarly regard the range of his own production?”7

The consideration of classification in the sciences influenced the thinking of French architect and professor of the Académie Royale d’Architecture Jacques-François Blondel. In his Cours d’Architecture of 1771,8 Blondel compiled an extensive list of varieties of buildings, such as theaters, libraries, prisons, and lighthouses, designating each of those groups of buildings as “genres” (the term suggesting a biological connotation). The Cours proposed an original strategy for understanding the history of architecture: rather than focusing on particular architects or monuments, the emphasis was placed on categorizing the building inventory as a collective endeavor developed over time, where authorship was relegated or eliminated.

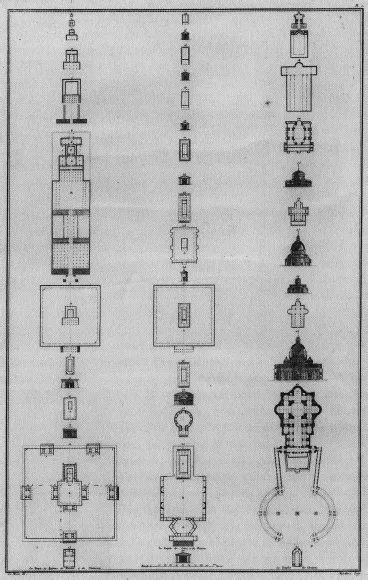

An alternative approach for classifying the architecture of the past was advanced by French historian Julien-David Le Roy (1724–1803). In his Les Ruines des plus beaux monuments de la Grèce (1758),9 Le Roy developed an innovative study of Greek temples. Instead of following chronological or stylistic criterion, he listed groups of buildings according to formal similitudes. The matrix of buildings deployed by Le Roy displays a notable resemblance to Linnaeus’s biological rubrics, thus advancing an innovative (and scientific) methodology for analyzing and classifying the built environment. This idea is illustrated in the figure titled “Parallel Between Ancient and Modern Temples” (Figure 1.1), where temples of different historical periods and styles drawn at the same scale were grouped according to planimetric similitudes, their positioning and alignment suggesting an evolutionary process. A notable feature of Le Roy’s approach was the coexistence of some of the most celebrated monuments together with lesser-known edifications—subscribing to the argument that science shouldn’t have qualitative predilections.10

The other issue impacting the eighteenth century’s intellectual debate was the notion of origins. Following a questioning of the biblical depictions of the beginnings of humankind, thinkers and scientists developed various theories regarding the origins of ideas, religions, languages, architecture, and artifacts created by early humans.11 Intellectuals and philosophers such as Voltaire, Montesquieu, Rousseau, and Condillac expressed a strong interest in the first civilizations, leading to the publication of numerous texts and essays explaining the beginnings of humankind. This interest was fueled by several factors, including recent archaeological discoveries in Egypt and Greece and publications about the colonial experiences in the American continents.

Figure 1.1 Le Moine, draftsman, Michelinot, engraver. Parallel between ancient and modern temples. From Julien-David Le Roy, Les ruines des plus beaux monuments de la Grèce, 2d ed. (Paris: Louis-François Delatour, 1770), plate 1. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

The Enlightenment’s academic and scientific interest in the question of origins had a profound influence on eighteenth-century architectural theory. As noted by Anthony Vidler,12 a consequence of this concern about the beginnings of architecture was the renewed consideration of the writings of Vitruvius. In Book 2, Chapter 1 of his treatise, Vitruvius describes how the first men gathered together around “the warm fire,” and “began in that first assembly to construct shelters.”13 Humankind’s first dwelling, according to this narration, was not a physical structure but a space delimited by the warmth emanated from the hearth. Architecture, therefore, was primarily a social setting.14

Vitruvius then discusses the evolution of architecture, establishing a linkage between the first constructions and their posterior developments:

By observing the shelters of others and adding new details to their own inceptions, they constructed better and better kinds of huts as time went on. And since they were of an imitative and teachable nature, they would daily point out to each other the results of their building, boasting of the novelties in it; and thus, with their natural gifts sharpened by emulation, their standards improved daily.15

(Italics added)

With this statement Vitruvius evinces the influence of the Aristotelian doctrine of imitation or mimesis, the process of adopting and later transforming a certain formal precedent. The history of architecture, according to this idea, is a prolonged chain of transformative iterations, where each building is both a derivation of anterior precedents and a new and original instance.

The Little Rustic Hut

The figure that best represents the impact of the question of origins in the architectural discourse during the Enlightenment is the Jesuit abbé Marc-Antoine Laugier16 (1713–69). With his Essai sur 1’architecture (An Essay on Architecture, 1753), Laugier exemplifies the ideological shift developed during the eighteenth century: a priest depicting an account of the origins of architecture that differs from the Catholic doctrine. In his preface, Laugier lays out the fundamental principles of architecture, concluding with what could be described as an intellectual epiphany:

Suddenly a bright light appeared before my eyes. I saw objects distinctly where before I had only caught a glimpse of haze and clouds. I took hold of these objects eagerly and saw by their lights my uncertainties gradually disappear and my difficulties vanished.17

What Laugier “sees” is the inevitable connection between the origins of architecture and its posterior development. His vision is epitomized by the image of the “rustic hut,” a form predestined to be endlessly imitated, the initiation of a sequence that would continue on through contemporary times.

Laugier’s account presents both similarities and differences to Vitruvius’s narrative. The most notable discrepancy is that while Vitruvius describes the first constructions as distant and historical events, Laugier presents the “rustic hut” as a metaphor of contemporary significance, an original form that would become a central concept for the architectural debate of his time. Laugier’s intention was to create the foundation of a theory that “firmly establishes the principles of architecture, explains its true spirit, and proposes rules for guiding talent and defining taste.”18 The primitive hut, therefore, may also be understood as an allegory,19 a guide to be considered and reflected upon by his contemporaries. Reaffirming this notion, Laugier writes, “All splendors of architecture ever conceived have been modeled on the little rustic hut I have just described.”20

Laugier’s “technological” accounts were much more detailed than those of Vitruvius. He describes the process of building the hut, how it starts with the selection of a site next to the banks of a river, follows with the assortment of materials (branches and logs), continues with the conversion of...