eBook - ePub

Scenic Art for the Theatre

History, Tools and Techniques

Susan Crabtree, Peter Beudert

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 414 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Scenic Art for the Theatre

History, Tools and Techniques

Susan Crabtree, Peter Beudert

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Now in its Third Edition, Scenic Art for the Theatre: History, Tools and Techniques continues to be the most trusted source for both student and professional scenic artists. With new information on scenic design using Photoshop, Paint Shop Pro and other digital imaging softwares this test expands to offer the developing artist more step-by-step instuction and more practical techniques for work in the field. It goes beyond detailing job functions and discussing techniques to serve as a trouble-shooting guide for the scenic artist, providing practical advice for everyday solutions.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Scenic Art for the Theatre un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Scenic Art for the Theatre de Susan Crabtree, Peter Beudert en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Médias et arts de la scène y Théâtre. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

PART ONE

THE PROFESSION OF SCENIC ARTISTRY

Scenic artists Steve Purtee and Ron Gottschalk executing the back drop for An American in Paris designed by Adrianne Lobel. They work on the paint deck at Scenic Art Studios in the New York area.

CHAPTER 1

THE PROFESSIONAL

SCENIC ARTIST

The work is nearly soundless, a simple manual activity. One brushstroke after another is made, each one intended to convey shape and meaning. Each brushstroke, every flick of spatter is applied with purpose and clear intention. Scenic painting is work that fully engages the mind and body. Are there leaves in this brush? Not literally, but does this quick bounce and push of the brush convey “leaf”? Ash or maple or oak? Facing the sunlight, blown in the wind, one on top of another making a branch, a limb, a tree. And then make another few trees.

This is the job of a scenic artist. Reflecting a vision of life through painting and painting things on a very, very large scale. Wearing grubby paint-covered clothes at work is the norm. It is a remarkably durable old-fashioned craft seemingly out of sync with the wireless 24/7 world. No virtual brushes yet. A scenic artist is, after all, a painter practicing a craft that has changed very little over the many centuries of its existence.

“The ancients required realistic pictures of real things,”1 wrote the Roman architect Vitruvius in De architectura, or Ten Books on Architecture, written sometime in the last century BC. This influential book was revised and published by Leon Battista Alberti during the Italian Renaissance. In De architectura, Vitruvius gives us the first written record of scenic artistry in describing Greek stage decoration and painting in the time of Æschylus. Throughout that 2,500-year time span, it is undeniable that the simple task of applying color to canvas with a brush has changed little. The craft of scenic art grew in importance tremendously during and after the Renaissance and the rediscovery of the rules of perspective. In the renaissance, the ability to draw in perspective was the greatest skill a scenic artist possessed, valued even over the ability to paint. The skill of drawing, now called cartooning, remained a subspecialty of scenic art for centuries following the Renaissance. Scenic artists further subdivided the painting craft into a range of specialties by the nineteenth century, including architecture, landscape, perspective, and fantastical scenes as in Figure 1-1. In the nineteenth century, it was the scenic artist who was the master of the stage image as both designer and painter. Remarkably, the act of painting for the stage today has changed little through the long span of time since scenic painting began. All the Industrial Revolution brought the scenic artist were motorized paint frames and better water-based paint. Only in the last 20 years has a truly fundamental technological change come to scenic art in the form of digitized artwork and mechanized “painting” on a large scale.

The beginning of the twentieth century brought a more profound aesthetic change to scenic artistry through the development of modern stage design and the separation of scenic artists and scenic designers. It was at that point in time that traditional two-dimensional painted scenery was critically reexamined in relationship to the presence of the human body on stage. Due to this critical reexamination of scenic painting as decoration, popular recognition of the work of the scenic artist disappeared rapidly from this point in time. It had been common for a scenic artist in the nineteenth century to be given ample recognition by the press and general public for their painting skills. Had People magazine existed 150 years ago, it would not have been uncommon to see in it pictures of famous scenic artists out on the town with young aspiring actors or actresses — such was their popularity and prominence. Painted scenery was very suddenly considered by some to be terribly old-fashioned and quaint by 1910: “Modern stage-craft has been born of a realization that painting itself is a minor part of stage setting.”2 This statement by Lee Simonson typified the outlook of the modern theatre practitioners during much of the twentieth century.

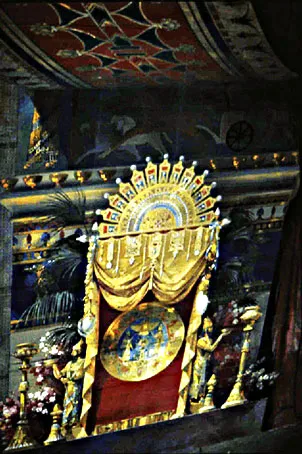

FIGURE 1-1 An example of traditional scenic painting style emulating nineteenth-century technique, possibly painted by a European artist brought to America. From the Lyric Opera of Chicago/Northern Illinois University Historical Scenic Collection (Courtesy of the School of Theatre and Dance, Northern Illinois University, Alexander Aducci, Curator).

The centuries leading up to the beginning of the modern stage design movement saw the development of spectacular scenic painting. The ability of the painted image to be spectacular, opulent, fantastical, and magical kept traditional scenic painting alive in the theatre. Somehow modern stagecraft and traditional stage painting were able to coexist, permitting scenic artistry to continue and flourish up to our own time. Theatre production without painting now seems unimaginable.

The best scenic artists today are unknown to the public, but are very well known and respected to the professionals who work with them. It is unheard of to have credit given in the program of a Broadway production to an individual scenic artist on the same level as a scenic designer. However, those of us who work in theatre know well that scenic artists are as much a part of the creative process as designers. Just as Broadway producers insist on the work of such gifted designers as Anna Louizos, John Lee Beatty, Scott Pask, and Tony Walton (to name but a few), it is inconceivable that any of these great designers would allow their work to be painted anyplace other than a major professional scenic studio.

To be a scenic artist is to earn a living by painting. It may mean that one is asked to work odd hours, often in odd locations. It may mean working on a different project almost every week of the year. It may mean not working at times, or at other times having more requests for your work than there is time in the day. It means that in all likelihood you have no office, you bring your tools with you, and you might not work with the same group of people regularly or in the same place. To be a scenic artist — specifically, a successful self-employed scenic artist — also means that you need to have good organization and business skills, as any self-employed person needs. A scenic artist is a loner in a world in which most people work for very large corporations. Some may see this as freedom; others may not be comfortable with the financial burdens of independence.

Being a scenic artist is hard physical work, too. The physical scale of the work is immense and you are nearly always on your feet, as in Figure 1-2. The artistic and emotional demands are great. The working day can be long, may be indoors or out, and may not always be predictable. It is not the sort of career one simply falls into because there is nothing better to do. One needs to seek out the practice, prepare oneself for it through a long period of training, and put out a fair effort to find work.

What may matter most is that being a scenic artist is profoundly rewarding. What other profession allows you paint all day long? If painting is what you want to do, there are few options for artists. Being a scenic artist is, after all, being an artist. Being a scenic artist allows you to paint and frequently paint things on a very grand scale. Thousand-square-foot canvases knocked out in one, two, or three days (or just a few hours) are not the stuff of everyday life, except for the scenic artist. This is what the scenic artist does, for it is a career of painting, plain and simple. That scenic art is also hard labor becomes apparent all too quickly to the young (and old) practitioner. And sometimes this reality is the thing we find hard to overlook. Yet who can deny the rich pleasure of the act of painting? When the canvas is primed and fresh, when the cartoon is ready and the colors mixed, it is exciting to lay down the first color on a drop. There is an immediate reward of a brush pulling on canvas and the proper stroke of paint. Does this not fulfill us in some profound way?

FIGURE 1-2 The shop floor at Scenic Art Studios, the only scenic shop in the New York City area devoted solely to scenic painting. Eric Stappach and Michalyn Monson work on the 2008 Fifi Award Ceremony designed by Chris Jones.

THE PROFESSIONAL SCENIC ARTIST

A scenic artist is a highly specialized painter who works on very large-scale and often realistic paintings. Yet this sort of painting is by no means all that scenic artists do. In fact, it is difficult to state exactly what type of painting a scenic artist will be required to do during the course of any given day. All professional scenic artists are certainly expected to be capable of painting large-scale backdrops, once the principal output of the trade and to this day a vital element of stage design. Contemporary scenic artists are also expected to adeptly paint two- and three-dimensional scenery by employing a wide array of painting techniques. Faux-finish techniques on three-dimensional surfaces are as common now as the traditional trompe l’oeil painting that is the foundation of scenic art.

Scenic artists may apply paint to canvas, linen, wood, plastic, foam, and metal as a matter of course. They paint objects while standing and objects lying down, requiring two different techniques. A scenic artist uses a palette of traditional colors in several formats and a variety of media as well as various texturing and finishing products and must be an expert in the use of these materials. They paint with brooms, sprayers, rollers, pumps, sponges, rags, feathers, and, of course, brushes. Sculpture and carving are skills expected of many scenic artists, especially in regional theatres (though at the top levels of the craft there are sculptors who sculpt and carve exclusively). Thus, knowledge of sculpting and crafting in wood, foam, fabric, metal, and other materials is also essential knowledge for the scenic artist, although not the focus of this text.

The Expectations of a Professional Scenic Artist

Successful scenic artists, like many artists of the theatre, need a wide array of skills and knowledge to serve them in their profession. The nature of the business of theatre means that scenic artists might encounter a job not knowing any of their colleagues or the designer whose work they will soon paint; nor would they know the producer who is paying them. However, the scenic artist will be expected to come with knowledge and skills at professional standards — skills common to scenic artists worldwide. Some skills are self-evident: all professional scenic artists must draw and paint very well. Scenic artists also must know their tools — paint and brushes — as well as how to work on surfaces they are called on to paint and the hundreds of products used in painting, staining, dying, sealing, texturing, thinning, extending, or chemically drying paint. Scenic artists also must possess knowledge in the areas of scenic design, drafting, calligraphy, and sign painting. In this profession, where visual images are reproduced on a large scale, such expertise is the foundational skill set.

In addition to these skills, exceptional scenic artists will have acquired a wide base of knowledge to support the visual images and effects that they are asked to create. Knowledge in the areas of art and art history (clearly necessary to successfully create an image such as Figure 1-3), architecture, architectural and theatrical history, photography, printing, mechanical image reproduction, and geometry and the natural sciences are all part of the body of knowledge that contributes to the day-to-day work of the scenic artist. A keen curiosity and good powers of observation help put this acquired knowledge to work. Travel and experience certainly contribute to the ability to synthesize one’s knowledge of the physical world. The abilities to call up these skills and to work quickly and without having to unnecessarily rework or overwork any step of the scenic painting process are necessary to call oneself a professional scenic artist.

Drawing and drafting are the skills scenic artists use when beginning a scenic image and are the basis of scenic painting. Nearly every scenic art project, particularly if it is trompe l’oeil, begins with an accurate drawing to guide the work. The drawing of architecture relies on the rules of geometry and linear perspective for precision. Geomet...