![]()

Chapter 1

FAMILY HISTORY

FORTY ACRES AND PHELPS HOUSE

Roger Sessions liked to tell a story that began with the novelist’s opening cliché: “It was a dark and stormy night.” The subject of the anecdote was his ancestry, and both a letter to George Bartlett and a diary kept by two participants reveal why this particular night would be memorable. At 4:00 p.m. on August 9, 1917, during World War I, violinist Quincy Porter and pianist Bruce Simonds gave one of their series of concerts of French and Belgian music at Amherst College.1 (Bartlett had arranged a similar concert in Webster, Massachusetts, on July 27.) These concerts were to raise money for the Red Cross; at a dollar a ticket they made $91.38 that August evening. Afterwards, 20-year-old Sessions and the two performers had a “wild time” at a dinner and musicale at Mme Bianchi’s, Emily Dickinson’s niece who lived in Austin Dickinson’s home next to where the poet had lived. Around 11:00 p.m. they “tore [them]selves away” from Amherst to leave for Sessions’s family home in Hadley. Sessions drove a horse-drawn cart powered by the family animal, Rex, with only one seat to accommodate “the three geniuses.”2 The skittish horse preferred to walk downhill and proceeded at a snail’s pace.

Rex also disliked thunderstorms, which soon enveloped the quartet. “Drove by ghostly barns,” Porter wrote, “illuminated by flashes of lightening. Strange flowing sound in the distance—nearer and nearer—covered up violin case by putting it in the bottom of the buggy and stretching feet over it.”3 They then “Drove furiously over the narrow road, boughs swishing past our faces; pitch blackness, except for the dim lantern on the buggy.” Sessions, who could not see with water streaming over his glasses, “disappeared into the darkness with the violin” to leave it for the night at his maiden aunts’—Arria and Molly Huntington’s—cabin, “lonely and surrounded by woods.” Sessions’s older sister Hannah answered the door. The aunts insisted on entertaining them—it was now midnight—so the trio tied up Rex and, soaked to the skin, the two performers “plunged through a tunnel of sopped bushes” (they were wearing summer concert attire and white pants) and reached the bungalow with no running water or electricity. The “storm raged outside in picturesque confusion, and we stood and dripped until dry enough to sit down.”4 All three signed the aunts’ guestbook: Simonds gave the date with time (12m–1 a.m.), and wrote in the “remarks” column, “Macbeth Act I, Sc. I;” Porter wrote “Noah’s Ark;” and Sessions inscribed “Après moi, le deluge.”5

Hannah (known as Nan) got dressed and talked with them, but aunt Arria, in night-clothes, conversed “from behind a screen [which was only proper for a Victorian lady] on the subject of genealogy.”6 Arria was born in 1848 and Molly in 1862, and Arria had written a book about her family history.7 The conversation between Quincy Porter and Sessions’s “1848 aunt” concerned whether their common ancestor was Hezekiah Porter, six generations back, or Eleazar Porter, five generations back. They concluded that the relative was Eleazar, and therefore the two musicians were fifth cousins, rather than sixth cousins. “So I mean, this is a dangerous subject, that’s all,” Sessions remarked later.8 “That kind of snobbish interest in family ancestors is oppressive, stifling, and dreadful. There’s an awful lot of Huntington family pride in [the book Forty Acres], and that always bored me very much.”9

The three decided to venture forth at 1:00 a.m. They led Rex through the mud, but a blinding flash sent them for cover in a nearby shed, where they stayed for 20 minutes. They started once again, Sessions “having discarded coat and necktie and clad in shirt, white flannels, best low shoes, and straw hat, leading the horse, Quincy similarly clad carrying the lantern, and Bruce sitting in the wagon, and all three of us singing at the top of our lungs like larks—of the genus polonius bacchanalis.”10 “Oceans of mud, and no cessation in the torrent. Steep down-hill,” Porter recalled. They discovered one of the workhorses loose and seeking shelter from the rain by the barn door of Forty Acres, the Huntington house. “Sharp lightening and thunder, put in at a shed after flash which dazzled us for three seconds, giving us splendid after-images.” They arrived at Sessions’s family’s home, Phelps House, about 1:40 a.m. “R[oger] bade B[ruce] go into the house and assure the family that we were alive, saying ‘Hello’ reassuringly as he opened the door: which B. did, but found the lower house deserted, and only after climbing the stairs, heard Mrs. S. say drowsily ‘Roge, is that you?’ Anticlimax. John appeared in pajamas. No one had worried, thought of us in Amherst.”11 Sessions’s mother Ruth and younger brother John also wanted to hear their exploits, which were retold. The three Yale musicians finally got to bed around 3:00 a.m.

All of the dramatis personae in this story (except Rex) shall return in fuller guise in this book. Their first appearance here is, however, emblematic of their characteristics and situations. Sessions, for example, may perhaps surprise the reader with his unexpected lustiness, his closeness to nature and animals, his ambivalence about his New England ancestry, and his sense of humor—even if revealed in jokes in Latin.

Figure 1 The hilltop cabin where Arria and Molly Huntington lived. It was struck by lightening and burned to the ground in 1948.

If this book were a mystery story rather than a biography (which, after all, tries to solve the mystery of a human being), we might ask some investigative questions. For example, who was Martha Bianchi (so different from her aunt, the reclusive poet Emily Dickinson)? Why were three student-age men working for the Red Cross instead of serving in Europe during World War I? Who was George Bartlett? Why was Nan staying with her aunts rather than with her mother and brother? Who were the Huntingtons, Porters, Phelpses, and Sessionses, and what role did they play in Sessions’s life? Perhaps the biggest mystery is the dog that did not bark in the night, as Sherlock Holmes would have put it: Where was the composer’s father, Archibald Sessions? In the coming pages the author shall strive to solve these puzzles.

Sessions said of his ancestral home across the street from Phelps House, “Forty Acres is haunted, you know. Very strange things have happened there. There’s even a secret passage. I love it very much, and I feel like one of the trees there.”12 It is “a wonderful old place, a beautiful place, but these things can have various implications. I’m very attached to it myself, in a way, but I have a kind of horror of it, too.”13 Sessions described Forty Acres and his background:

We have an old, old family house in Hadley, Massachusetts, right on the Connecticut River. It’s a wonderful old house. One of my ancestors was one of the founders of Hadley. In 1752 Moses Porter decided it was safe to build a house outside the town stockade. Sometimes it was subject to attack by the Indians, even by the French from Canada. Porter was a captain in the [colonial militia].

I remember my grandfather. He died when I was seven years old. He became bishop of Central New York. First he was a Unitarian minister. He became a professor of Christian Knowledge [Morals] at Harvard. Then he got bored, so to speak, with the Unitarian church, and joined the Episcopal church and became a minister in Boston, and then became bishop of Central New York….

He married a wonderful lady from Boston. I always told people I had a grandmother complex. She was descended from a man who was a general in the revolutionary war.14

Sessions has been pegged by critics as a Puritan New Englander. “I’ve run across that in my career, because my music was supposed to be very New England and so forth and austere. Of course, it’s just the opposite. I don’t think anybody who has ever known me has thought I was conspicuously austere.”15 Nevertheless, religion played an important role in his family.

Moses Porter, the builder of Forty Acres, had been, like all of the Bishop’s ancestors, a Puritan. A succession of five Elizabeths, mothers and daughters, grew up in Hadley at Forty Acres. Elizabeth Phelps, the third Elizabeth, married—on the first day of the nineteenth century, January 1, 1801—Dan Huntington from Connecticut. They had eleven children, of whom Elizabeth Huntington was second oldest and Frederic Dan the youngest.16 The father, Dan Huntington was a retired clergyman. Elizabeth Phelps Huntington had been influenced by William Ellery Channing, whose books persuaded her to believe no longer in devils and hell or the Trinity, but rather to believe in human goodness and the power of reason. Church pastors in Hadley warned her not to rely on Channing’s Unitarianism; she would be expelled from the Calvinist church if she did not give it up.

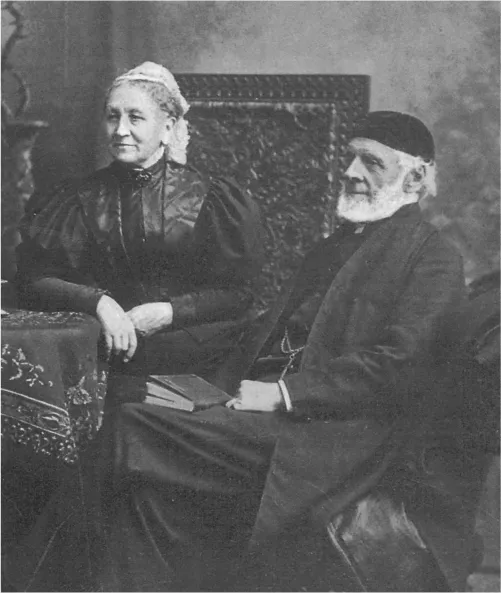

Indeed, a delegation in two buggies appeared at Forty Acres to belabor the heretic. After repeated stern visits, they cut both Huntington parents from the communion with the Hadley Calvinist congregation. The couple became Unitarians. Their youngest son, Frederic Dan, who was graduated from Amherst in 1839 and from Harvard Divinity School in 1842, became a popular Unitarian minister. Because of this faith, his education, and ability to preach, he was made Preacher to the University and Plummer Professor of Christian Morals at Harvard College in 1855. He was Sessions’s maternal grandfather.

It turned out, however, that Frederic Dan Huntington had a great deal in common with his heretical mother. In 1861 he underwent a religious conversion: he felt closer to a Trinitarian theology and converted to Episcopalianism. Many ties were severed with the Harvard community when he, his wife Hannah Dane Sargent, and his oldest of five children George were confirmed in the Episcopal Church.17 Frederic Dan Huntington accepted the rectorship of Emmanuel Church in Boston. Sons George and James were graduated from Harvard, and George attended divinity school. Their sisters were Arria, Ruth, and Molly.

Ruth Huntington was born in Cambridge in an old house on the corner of Quincy Street and Massachusetts Avenue overlooking Harvard Square. Her parents had seven children of whom five survived. They were: George Putnam (1844–1904); Arria Sargent (1848–1921); Charles Edward (born October 2, 1852; died October 17, 1852); James Otis Sargent (1854–July 1, 1935); William (born and died on the same day in July 1856); Ruth Gregson (November 3, 1859–December 2, 1946); and Mary Lincoln (known as Molly; 1862–1936).

Figure 2 Hannah Dane Sargent and Bishop Frederic Dan Huntington, 1895.

Like her husband, Ruth came from a family in which two siblings did not live long. Besides Ruth, only George married; he married Lilly St Agnam Barrett (1848–1926). They had eight children of whom six, five sons and a daughter, survived.18 One son, Michael Paul, became an Episcopal priest like his father and grandfather. These six Huntingtons were Sessions’s only first cousins on his mother’s side.

Ruth grew up in the 1860s at 68 Bolyston Street facing the Boston Public Garden. The home boasted a square Chickering piano in the living room (the Chickering factory was several blocks west). Back Bay was still just that, a broad body of shallow water. Her father’s church, Emmanuel Church, was nearby on Newbury Street. Entering it today one can see on the left a bas-relief portrait of its rector Frederic Dan Huntington.

The Huntington children felt they were at the center, the “hub,” as Boston was famously described, of the universe. Ruth’s grandmother lived in Roxbury; she was the daughter of Abner Lincoln, a son of General Lincoln, George Washington’s aide-decamp. Ruth’s mother, Hannah Dane Sargent, was one of five children of Epes Sargent and Mary Lincoln. The Sargents lived in a huge Boston house.

Having a cook, maids, a dressmaker, and the respect of the upper crust of Boston society gave Ruth a sense of entitlement that never left her. All four of her siblings, however, responded to their situation quite differently from her—with self-abnegation: the two brothers became priests, and the two sisters, spinster aunts who worked for decades for social betterment. Although Ruth did some good works, including teaching Indians music in Syracuse, she never lost a desire for praise and admiration, for which the Bishop admonished her. “From all accounts R’s visit [to Cornell] in Ithaca,” the Bishop wrote, “was a very gay one. I have no doubt she enjoyed it, but with her weakness for admiration and pleasure, to which such experiences pander, I fear it may not have been a helpful influence.”19 Furious, Ruth argued the point with her mother, but the Bishop understood her perfectly.

The most important thing to know about Ruth Sessions is that she was born a Huntington. A direct ancestor, Samuel Huntington, was a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Like Scarlett O’Hara’s attachment to the fictional Tara, Ruth’s attachment to her father and to Forty Acres would trump all other considerations in her life. Sessions recalled, “I used to say all ladies were in love with their fathers at that time. And of course when the father was a bishop, he was the old man of the tribe.”20

Ruth Sessions’s granddaughter, Sarah Chapin, described her “complex personality—kind, sympathetic, generous, resourceful, treacherous and combative. Growing up in a family dominated by her father, with two older brothers and a sister solidly involved in the church, the Fourth Child (as she called herself) carried a heavy burden of responsibility to follow them into church work, but to everyone’s distress she developed ‘nerves.’ … The attacks continued throughout her long life causing powerful repercussions for her and everyone around her. It is by no means clear, however, that her attacks were always calculated and deliberate; they only seemed that way to her hapless relatives.”21

Ruth’s autobiography, Sixty-Odd; A Personal History, published in 1936 but ending its narrative in 1920, is our major source about her. The eminently readable book reveals a writer of considerable skill in evoking time and place. She had plenty of previous writing experience, having published stories, essays, and children’s books. Her life was certainly adventurous—she had met famous...