eBook - ePub

Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart

Le Nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni

Wye Jamison Allanbrook

This is a test

Compartir libro

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart

Le Nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni

Wye Jamison Allanbrook

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Wye Jamison Allanbrook's widely influential Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart challenges the view that Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's music was a "pure play" of key and theme, more abstract than that of his predecessors. Allanbrook's innovative work shows that Mozart used a vocabulary of symbolic gestures and musical rhythms to reveal the nature of his characters and their interrelations. The dance rhythms and meters that pervade his operas conveyed very specific meanings to the audiences of the day.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart de Wye Jamison Allanbrook en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Media & Performing Arts y Music. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

Media & Performing ArtsCategoría

MusicPART ONE

MOZART’S RHYTHMIC TOPOI

—There is, continued my father, a certain mien and motion of the body and all its parts, both in acting and speaking, which argues a man well within; and I am not at all surprised that Gregory of Nazianzum, upon observing the hasty and untoward gestures of Julian, should foretell he would one day become an apostate;—or that St. Ambrose should turn his Amanuensis out of doors, because of an indecent motion of his head, which went backwards and forwards like a flail;—or that Democritus should conceive Protagoras to be a scholar, from seeing him bind up a faggot, and thrusting, as he did it, the small twigs inwards.—There are a thousand unnoticed openings, continued my father, which let a penetrating eye at once into a man’s soul; and I maintain it, added he, that a man of sense does not lay down his hat in coming into a room,—or take it up in going out of it, but something escapes, which discovers him.

—Lawrence Sterne, Tristram Shandy, vol. 6, chap. 5.

CHAPTER ONE

The Shapes of Rhythms

Meter, Dance, and Expression

It should not come as a surprise, in light of what has been said, that meters can in themselves possess affects. Although meter is an element of music which in general we consider as merely a handy temporal measure (beneath the threshold of expressive values), a meter is usually the first choice a composer makes, and all signs indicate that in the late eighteenth century that choice amounted to the demarcation of an expressive limit. One finds in glancing through the writings of late eighteenth-century theorists that a description of the expressive qualities of meters is regularly included in discussions of how to “paint the passions”:

Tempo in music is either fast or slow, and the division of the measure is either duple or triple. Both kinds are distinguished from each other by their nature and by their effect, and their use is anything but indifferent as far as the various passions are concerned. . . .

Composers rarely offend in this matter [the affects of various tempos], but more often against the special nature and quality of various meters; since they often set in 4/4 what by its nature is an alla breve or 2/4 meter. With 6/8 meter the same confusions occur often enough, even with well-known composers, and in cases where they cannot use as an excuse the constraint occasionally placed upon them by the poet. Generally many composers appear to have studied the tenets of meter even less than those of period structure, since the former is cloaked in far less darkness than the latter.1

Music is based on the possibility of making a row of notes which are indifferent in themselves, of which not one expresses anything autonomously, into a speech of the passions. . . .

[Meter’s role in the “speech of the passions”:] The advantages of subdividing triple and duple meter into various meters with longer or shorter notes for the main beats are understandable; for from this each meter obtains its own special tempo, its own special weight in performance, and consequently its own special character also.2

But it is clear from the little I have said here about the different characters of meters that this variety of meters is very suitable for the expression of the shadings of the passions.

That is, each passion has its degrees of strength and, if I may thus express it, its deeper or shallower impression. . . . The composer must before all things make clear to himself the particular impression of the passion he is to portray, and then choose a heavier or lighter meter according to the affect in its particular shading, which requires one or the other.3

It makes sense that meter—the classification of the number, order, and weight of accents—should take on an important role in an aesthetic which connects emotion with motion. Since meter is the prime orderer of the Bewegung or movement, its numbers are by no means neutral and lifeless markers of time, but a set of signs designating a corresponding order of passions, and meant in execution to stir their hearers directly by their palpable emanations in sound. The composer can study the shapes of meters to learn their potential for expression, he can manipulate them, but he did not invent them.

Yet it is frequently assumed that this notion, although a signal principle of the Affektenlehre theories of the early part of the century, had dropped out of fashion by the late 1700s, at the same time as the number of time signatures in use had declined and qualifying adjectives were being more frequently employed at the head of a movement to indicate the proper tempo—and character—of the work.4 In the face of this opinion it is striking that late eighteenth-century theorists’ discussions of rhythm and meter remained as detailed as those of their counterparts earlier in the century;5 accounts of the subject in lexicons, manuals, and treatises spelled out carefully the individual configurations of each time signature in current use and of many which had fallen into disuse.6 J. P. Kirnberger’s classification ran to twenty-eight meters,7 and Carlo Gervasoni, writing around the turn of the century, still treated under separate headings as many as sixteen.8

Kirnberger sketches out the form he considers the discussion of any given meter should take, listing three main heads, the first two of which are especially relevant here (the third concerns the special case of the setting of texts):

1) That all kinds of meters discovered and in use up to now be described to [the composer], each according to its true quality and exact execution.

2) That the spirit or character of each meter be specified as precisely as possible.9

Most theorists’ discussions tend to follow this sketch, with the result that the meters examined settle into a sort of affective spectrum, or gamut. Consider first the lower number of the time signature—the designator of the beat. From the beginnings of Western polyphony a particular note value has usually been tacitly considered to embody what I shall call the tempo giusto, the normal moderate pace against which are measured “faster” and “slower.”10 By the eighteenth century the valore giusto had become the quarter note and, insofar as there is a modern notion of tempo giusto, it remains so today. In eighteenth-century French music, for example, 3/4 was often expressed by the single symbol 3, presumably in recognition of its status as the normal or tempo giusto among triple meters.11 A spectrum of meters is readily organized around the lower number of the time signature, radiating in each direction from the central number 4; both tempo and degree of accentuation are established by the relative duration of the note receiving the beat:

As far as meter is concerned, those of longer note values, such as alla breve, 3/2, and 6/4, have a heavier and slower movement than those of shorter note values, such as 2/4, 3/4, and 6/8, and these are less lively than 3/8 and 6/16. Thus for example a Loure in 3/2 is slower than a Minuet in 3/4, and this dance is again slower than a Passepied in 3/8.12

The meters written on the staff all indicate a particular performance. In meters, for example, with notes of long duration, execution must always be slow and sedate, in conformance with the large note values; but in meters with notes of only short duration a lighter execution is required, since these notes by their nature must be passed over quickly. Thus, independently of the degree of tempo, meters are regulated also by the various values of the notes.13

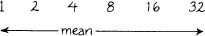

The quarter note, measuring the motion of a normal human stride, occupies the center of the spectrum. Meters in half notes (2) or whole notes (1, although rare, is mentioned in some treatises) fall to the left of center, requiring a slower tempo and a more solemn style of execution. To the right fall 8 and 16 (and, at the beginning of the century, 32) in ascending degrees of rapidity, lightness, and gaiety. Thus a geometric series of numbers from one to thirty-two corresponds to an ordered range of human strides from the slowest (and gravest) to the fastest (and gayest):

The affect projected by the meter is a direct consequence of the union of tempo and degree of accentuation:

Sorrow, humility, and reverence, require a slow movement, with gentle, easy inflections of the voice; but joy, thanksgiving, and triumph, ought to be distinguished by a quicker movement, with bolder inflexions, and more distant leaps, from one sound to another.14

And so the number exemplified by meter is viewed as a “passionate” number, capable of embodying the em...