![]()

Chapter 1

Czechs, Germans, and the Borderlands before 1945

“Our first goal . . . must be to cleanse the entire republic completely of Germans,” declared Prokop Drtina in May 1945.1 The future minister of justice of Czechoslovakia’s reconstituted government, Drtina echoed a common formulation that accompanied the first wave of expulsions of the country’s German population. His widely shared assumptions were that national identity was a fixed and concrete category, and that material spaces had national coordinates that could be reset through cleansing. Drtina and other backers of the 1945 expulsions sharply delineated Czech space and German space on their maps of Czechoslovakia, vastly simplifying both the historical and contemporary social reality of borderland communities. Their intention was, literally, to wipe the map clean, removing the German population and replacing it with Czechs.

The reification of nation and nationalization of space in Czechoslovakia had roots in late nineteenth-century nationalist struggles in Habsburg Bohemia. In the 1880s, Czech and German activists reframed ongoing disputes over language rights as a “battle for national property” in the borderlands of Bohemia. Each side sought to fortify and expand its linguistic territory by building schools, boycotting shops, and intensifying national identification among often indifferent local residents. But contrary to nationalist claims, Czechness and Germanness were not inevitable products of Bohemia’s linguistic diversity. Hundreds of thousands of Bohemia’s inhabitants were bilingual, and even many monolingual citizens were indifferent to nationality politics in the late Habsburg monarchy. Convincing people to be national Czechs and Germans took a lot of work by activists, who were often frustrated by their lack of success.2

In fact, Bohemia’s Czechs and Germans had far more in common than nationalists asserted, and than historians have often credited. Czech and German national movements in Bohemia were inseparable from each other, their histories bound both by constant reference to the other and by shared landscapes, rhetoric, strategies, and political context. This chapter brings these intertwined narratives to the brink of the 1945 expulsions, the imminent end of Czech-German cohabitation in the Bohemian lands. One goal is to explain why Czechs had the desire and ability to cleanse the borderlands of Germans after the Second World War. But most of this book is about the aftermath of the expulsions: the cultural, social, and physical transformation of the borderlands after 1945; the symbolic importance of the borderlands for Czech officials, settlers, and dissidents; and the persistent prominence of former Bohemian homelands in German memory and political culture. Accordingly, this chapter stands as background for much more than the expulsions themselves. It is a history of the borderlands as a shared space, rather than simply a stage for the mutual antagonism of Czechs and Germans. It emphasizes shared histories, including a shared history of conflict.

TOURING THE BOHEMIAN BORDERLANDS

In 1937, the British journalist-historian Elizabeth Wiskemann toured Bohemia and Moravia to research a book on the German minority problem in Czechoslovakia. Funded by Arnold Toynbee’s Royal Institute of International Affairs, she published Czechs and Germans in mid-1938, just as the so-called Sudeten crisis was reaching a peak.3 Later that summer, the British magnate Walter Runciman, sent by Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain to mediate between Czechs and Sudeten Germans, carried Wiskemann’s book with him to Czechoslovakia.4 Her book offered a history of Czech-German relations in the Bohemian lands, followed by a tour of the Sudetenland and exploration of contemporary Czechoslovak minority politics. It is worth revisiting Wiskemann’s tour, with some additions from other sources, as it provides a useful overview of the physical, economic, and linguistic geography of the Bohemian and Moravian borderlands amid escalating nationalist tensions in the late 1930s.

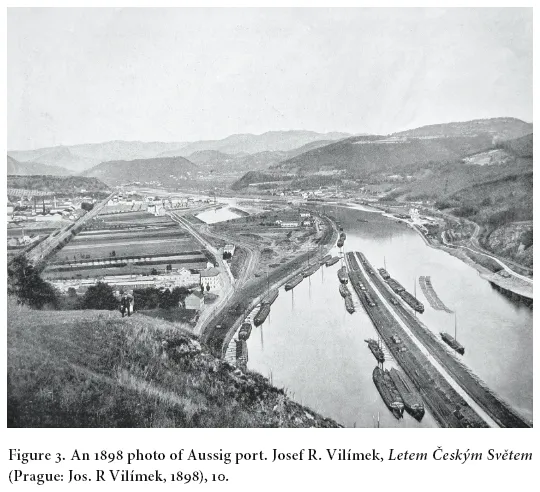

Wiskemann’s tour began in northern Bohemia, the most populous, industrialized, and mountainous of the regions known collectively as the Sudetenland after the mid-1920s. The Elbe (Labe) River flows north through Aussig (Ústí nad Labem) and Tetschen (Děcín), winding its way through a gap in the mountains to Germany. In the late nineteenth century, Aussig had been the busiest port in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, carrying trade to central Germany, to Hamburg, and beyond.5 Other than its port, Aussig was known for its chemical industries, while north Bohemia’s other major city, Reichenberg (Liberec) was the center of a region of textile factories and glassworks. Though punctuated by small industrial towns, much of the borderland from Aussig east to Reichenberg struck Wiskemann as “a fairy-story landscape with steep hills and pine forests and old, delighting villages.”6 Though highly industrialized and urbanized, northern Bohemian inhabitants lived in small cities and were not far from fields, forests, and mountains. Though hard-hit by the Great Depression of the early 1930s, Wiskemann noted, north Bohemian workers “at least have fields and fresh air around them. The soil in the mountainous frontier region is poor, but many working-people are not quite divorced from it, and this helps them to be able to keep a cow or a goat, and to be able to grow potatoes.”7

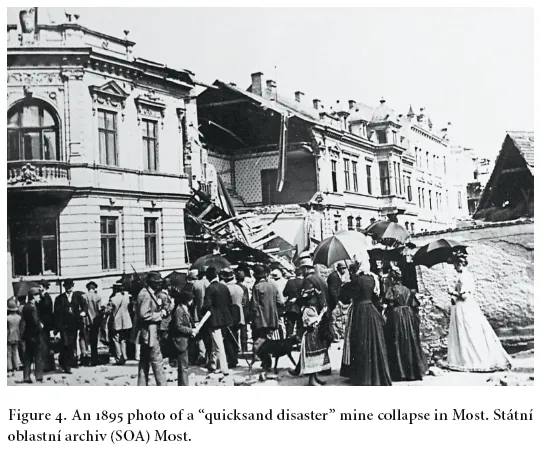

West of Aussig, Bohemia’s coal country began, a lignite (brown coal) basin that stretched for seventy kilometers along the base of the Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge/Krušné hory). When Wiskemann visited in 1937, most of the coal mining still took place in shafts below the ground, though there were some early strip mines in the vicinity of Brüx (Most), the region’s thriving center.8 Lignite’s low energy density and high moisture content make it inefficient to transport long distances, so it was burned in homes, power plants, and chemical factories locally. The mining district was filled with contrasts. Around Brüx and Dux (Duchcov), Wiskemann wrote, “the poverty is great and the smell of lignite hangs in the air,” but the forested mountains were only a short hike away.9 The pretty spa town of Teplitz (Teplice) sat amid the mines; so close, indeed, that in 1879 and 1892, miners had inadvertently broken through into the spa springs, leading to massive flooding of the mines, temporary closure of the spa, and several fatalities.10 Mine collapses were infrequent, but devastating. The 1890 and 1895 “quicksand disasters” in Brüx destroyed several buildings near the town center and killed two dozen miners.11

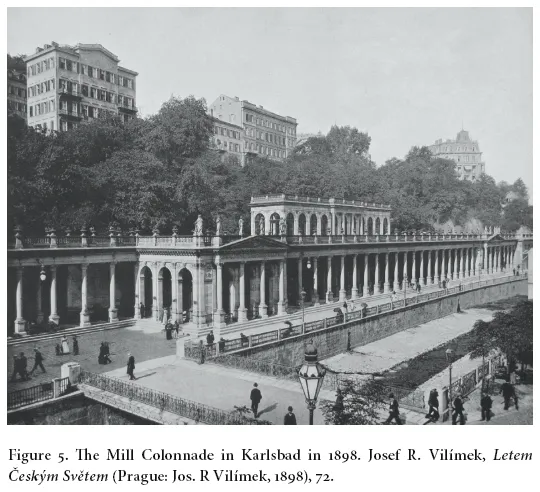

Continuing west and south among the foothills of the Ore Mountains, Bohemia’s famous spa triangle began. Karlsbad (Karlovy Vary) had long provided hydrotherapy and social opportunity to Europe’s elite, though Marienbad (Mariánské Lázně) and Franzensbad (Františkovy Lázně) in the Egerland also had their own dedicated clientele. In the nineteenth century, according to the German spa expert Sigismund Sutro, Karlsbad’s waters were the preferred treatment for gout, digestive difficulties, and “abdominal inaction,” while Marienbad was recommended to patients with lymphatic disorders, “hepatic engorgement, inaction of the bowels, haemorrhoidal congestion, or . . . any of the numerous evils due to luxurious and sedentary living without corresponding muscular exercise.”12 The water cure was usually accompanied by a walking cure in surrounding hills. In Karlsbad, Sutro wrote, “picturesque and wild scenery constantly alternates with beautiful park-like clusters of trees; green meadows, with woody hills; dark shady walks, with widely-spread open prospects.”13

Franzensbad was popular with “men of business or learning, who had been fixed to the writing-table the whole year,” spending a month at the spa “with a great deal of exercise in the open air, and relaxation from the usual mental exertion, [in order to free] themselves from the accumulated morbific matter.”14 We can see in these descriptions that contemporaries understood spas as a tonic for the ills of modern existence. And all three spas were known for their grand social life, with Karlsbad the most opulent. A 1903 spa guidebook marked it as “a picture which is scarcely seen in any other place in the world. Members of reigning families, princes, statesmen, literary men, merchants from every part of the world and in all possible costumes” lined up each morning under the neoclassical arcades to take the waters.15

By contrast, only a few kilometers from “the international luxury of Karlsbad,” Wiskemann wrote, “the Erzgebirge villages always lived in miserable poverty, for the soil is wretchedly poor and communication extremely difficult.”16 Some smaller towns outside of Karlsbad specialized in ceramic production, while artisans in Graslitz (Kraslice) and Schönbach (Luby) made a living crafting musical instruments out of distinctive local wood.17 With the late nineteenth-century discovery of radium, exhausted silver mines in Joachimstal (Jachymov) found new life, though miners’ lives were often shortened by cancer and respiratory ailments.18 A small luxury spa featuring radioactive waters opened near the mines in 1910, followed in the 1920s by a company that exported radium-laced soaps, shampoo, and other health products.19 Beyond a modest tourist industry, the Ore Mountains only sustained niche industries and were known for their impoverished inhabitants.

The western edge of the Egerland, dominated by the old cities of Eger (Cheb) and Asch (Aš), offered yet another contrast with the cosmopolitan spa towns to the east. The Eger region struck Wiskemann as distinctly un-Bohemian. Coming west from Karlsbad, the traveler “has left the Bohemian mountains behind and crossed some quite definite frontier into Western Germany.”20 The local Germans seemed more akin with the Bavarians across the border than fellow Sudetenlanders, and the Egerland had long been a nest of Reich-oriented pan-Germanism. Almost devoid of Czech speakers, the region’s cities successfully defied a government mandate to post bilingual signs after 1919.21

Though German speakers ringed most of the borders of Bohemia and Moravia, the southern part of this ring was sparsely inhabited. Mountainous and heavily forested like the north, the region largely lacked mineral resources and related industries. As Wiskemann put it, this small, “exceptionally poor population living on very poor soil” was dominated, even as late as the 1920s, by the great landowning aristocratic families, the Schwarzenbergs and Buquoys.22 The Schwarzenberg castle towered over the regional center at Krummau (Český Krumlov), an “exquisite little town” that has since become a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Forestry and beer were the leading industries in south Bohemia, the former enriching the noble landowners and the latter besotting the local inhabitants. To be fair, though, beer was a staple of diets across Bohemia. The largest south Bohemian breweries were in the regional metropole, Budějovice (Budweis), which was technically not in the borderlands. Long considered a German city, Budějovice had a sizable Czech majority by 1918.23

The border regions of southern Moravia were also mountainous and poor, though their proximity to Vienna offered a ready outlet, at least until 1918, for those looking for work.24 National identification proved particularly supple in Moravian borderland towns like Znaim (Znojmo), which registered 85 percent German in the 1910 census and 32 percent German in 1930.25 Wiskemann attributed the shift to widespread bilingualism and a certain ethnopolitical flexibility among the region’s residents.26 Like Budějovice, the Moravian capital Brno (Brünn), sat just north of the borderland region, though it too had a long history of bilingualism and a sizable German-speaking minority. In a typical maneuver after the founding of the Czechoslovak state in 1918, Czechs took control of city government by incorporating the overwhelmingly Czech suburbs into the city. German nationalists in Brno and many other mixed cities remained bitter in the 1930s over their loss of municipal control. In the interior, Moravia also had substantial German “language islands” in the larger cities of Iglau (Jihlava) and Zwittau (Svitavy).

Wiskemann concluded her tour of the borderlands with a stop in the Czech-German-Polish mining and industrial region known as Austrian Silesia, or after 1918, also as Czech Silesia.27 Abutting northern Moravia and Polish Silesia across the border, the region had much in common with northern Bohemia, including coal deposits and a well-developed textile industry. Ostrava also had the massive Vítkovice (Witkowitz) iron and steel works, once the largest in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. As in many of the mixed industrial cities in the northern Bohemian borderlands, nationalists often tried to mobilize social divisions between Czech laborers and German managers in Silesia, even as many inhabitants moved fluidly between Czech and German identifications, depending on their interests.

THE CONSTRUCTION OF NATIONAL COMMUNITIES IN THE BORDERLANDS

Though German speakers had lived in the Bohemian, Moravian, and Silesian borderlands for centuries, the idea of the borderlands as a Germanic national-political space gained currency only in the last decades of the nineteenth century. Czech and German speakers in the Bohemian lands of the Habsburg monarchy had at first been little touched by the populist idea of the nation that radiated across Europe with the French Revolution of 1789. The vast peasant majority of the provinces had little political awareness and tended toward local and religious identifications. Educated inhabitants considered themselves Bohemians and Habsburg subjects, but rarely national Czechs and Germans.

From the late eighteenth century, a handful of noble-sponsored patriotic societies touted science, education, and economic development in order to modernize Bohemia and Moravia. Though inspired by Enlightenment ideals, these societies also promoted the provinces’ distinct history and prerogatives in the face of Habsburg centralization.28 Patriotic nobles, together with a small Czech-speaking intelligentsia, prized the Czech language, both as the tongue of the Bohemian lands’ peasant majority and as the language of the Bohemian Kingdom before its acquisition by the Habsburg monarchy in the sixteenth century. By the 1840s, a growing Czech middle class had largely co-opted Bohemia’s patriotic societies, using them to promote Czech literacy, history, and culture. Soon these early Czech nationalists left their aristocratic patrons behind. “I am neither a Czech nor a German,” Count Josef Mathias Thun wrote plaintively in 1845, “but only a Bohemian. . . . Let us all be Bohemians!”29 But by the revolutionary year of 1848, educated Czechs preferred linguistic nationalism to Thun’s territorial patriotism.

Economic and social modernization reinforced this trend in the latter half of the nineteenth century, both by spreading national consciousness to peasants and workers and by creating new social tensions between Czech and German speakers. Bohemia and Moravia were among the earliest provinces to industrialize in the Habsburg monarchy, with substantial textile, food processing, mining, and metallurgical industries developing after the mid-nineteenth century. Public schooling and literacy expanded and were nearly universal for...