![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Persistently Misunderstood

The What Ifs of Shiloh

Timothy B. Smith

In the center of Shiloh National Military Park stands one of the most impressive monuments on the battlefield. The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) monument, erected in 1917 at a cost of $50,000 and dedicated in front of a crowd of fifteen thousand, is very impressive in its elegant lines, moving statuary, and symbolism. Erected with money raised by school children and the ladies of the South to mark a battlefield at that time (and still today) sharply tilted toward Union memorialization, the UDC monument loudly proclaims the honor and duty of Confederate soldiers at Shiloh.1

Besides the beauty, elegance, and size of the monument, the symbolism it portrays is perhaps most important. Placed on the battlefield in the heyday of the Lost Cause movement wherein proud Southerners sought to explain their defeat in the Civil War, the symbolism of the monument is classic Lost Cause. The bronze figures adorning each flank represent the four branches of the Confederate army (infantry, artillery, cavalry, and officer corps), with each providing their own view of the fighting. For instance, the infantry and artillery proudly look to the field while the cavalryman, little used in the heavily wooded terrain, spreads his hands in frustration and the officer bows his head in defeat. The heads on each side represent the two days of battle, with eleven (for the number of Confederate states) on the right denoting the first day’s fighting and lifted up in victory and the ten (fewer because of casualties) on the left bowed in defeat on the second day. Even the placement of the monument, at the high water mark of the Confederate struggle on the first day where the Hornet’s Nest defenders surrendered, speaks volumes.2

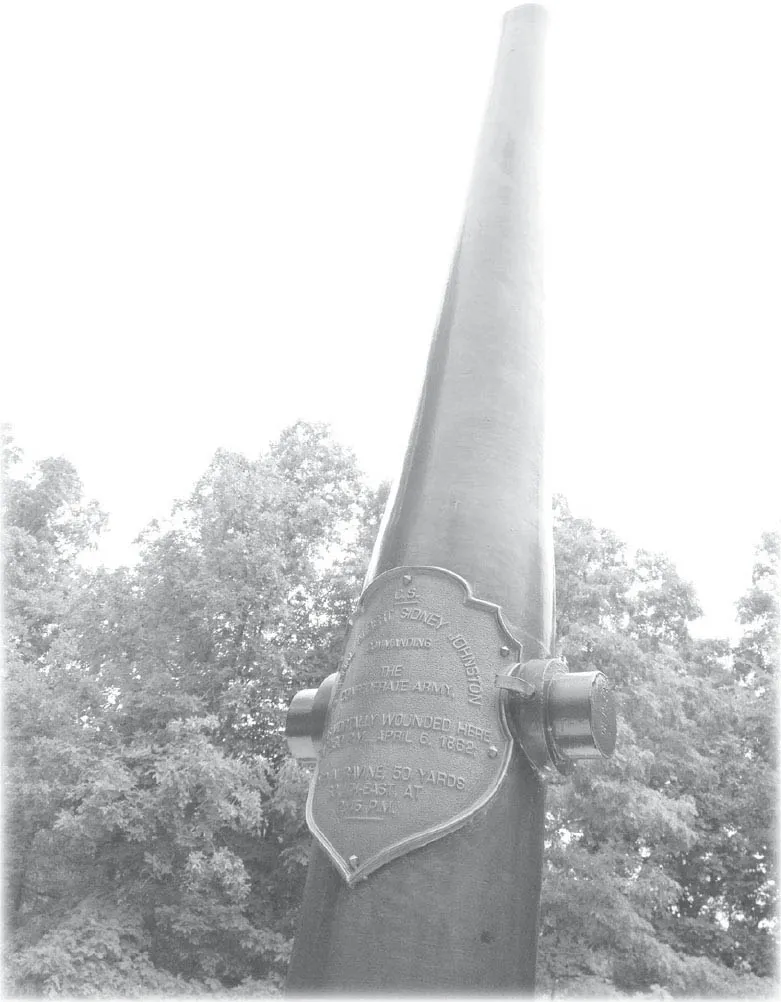

The most symbolism resides, as would be expected, in the center of the monument. There, three bronze figures are caught in a seeming dance of defeat. Two veiled figures are taking from a front feminine figure a laurel wreath. The two veiled figures represent death and night, and they are symbolically taking the laurel wreath of victory from the figure in front, who represents the South. In effect, the Lost Cause argument is that death and night stole victory from the Confederates at Shiloh, the night of April 6, 1862, coming too quickly and many Confederates later arguing that if they just had a few more hours of daylight the victory would have been complete. Similarly, death stole victory from the Confederacy in the form of Albert Sidney Johnston, whose bust profile can be seen directly below the three central bronze figures. Many Southerners argued that had Johnston not perished on the battlefield, he would have continued the victory on to fulfillment while his successor threw away the triumph. As a result, the what-if questions have long raged over what would have happened if Johnston had not died or if his successor had not thrown away the victory by calling off the assaults because of looming darkness.3

These questions are central to understanding Shiloh as a whole, and they are certainly not new, and they were not in 1917 when the two foremost what ifs were put on such beautiful display. The question of what would have happened had Johnston not perished or if P. G. T. Beauregard had not called off the final attacks of the day due to the lateness of the hour have been debated since the battle ended and well before their Lost Cause personification in 1917 in the UDC monument. No less an authority than Ulysses S. Grant himself wrote in 1885 that Shiloh “has been perhaps less understood, or, to state the case more accurately, more persistently misunderstood, than any other engagement … during the entire rebellion.” Similarly, the first park historian David W. Reed wrote in 1912 that “occasionally … some one thinks that his unaided memory of the events of 50 years ago is superior to the official reports of officers which were made at [the] time of the battle. It seems hard for them to realize that oft-repeated campfire stories, added to and enlarged, become impressed on the memory as real facts.”4

Lew Wallace, ordered to join the rest of the Federal army at Shiloh, took an alternate road—one that ultimately would have led him onto the battlefield on the left flank of an unsuspecting Confederate army. Instead, he doubled back to take the main road and got to the battle late. What if he had continued on his original path instead? Library of Congress

Certainly, many other what if scenarios abound at Shiloh as well, including questions such as what would have happened if the Confederates had managed to attack on April 5 instead of the next day? What would have happened if Buell had not arrived at the end of the first day? What would have happened if Lew Wallace had not been delayed in arriving on the field? What would have happened if Benjamin Prentiss and W. H. L. Wallace had not held the Hornet’s Nest to the point of sacrifice? The evidence indicates that few if any would have made much of a difference if the “what if” had been true. The record is clear that the paltry number of troops Buell managed to put into line on the evening of the first day made little difference in blunting the Confederate attack. Consequently, had the Confederates attacked as intended on April 5 or even April 4, as some historians claim but the evidence does not back up, the same problems would have appeared to stymie the Confederate advance short of Buell’s arrival, which made little actual difference in reality. So his absence would not have made much difference a day or two earlier. As Grant was able to hold his final line at Pittsburg Landing without Lew Wallace’s arrival, he certainly could have done so if he had shown up on the battlefield hours earlier, making the Confederate advance only that much more difficult. And finally, would a lesser defense of the Hornet’s Nest have given the Confederates a victory? Modern research and a growing school of thought is that Grant’s final line was so strong and was developed so early in the day (started around 2:30 p.m.) that Wallace and Prentiss holding out until nearly dark provided little additional benefit. Certainly, Ulysses S. Grant did not single the Hornet’s Nest defense out as the key to victory.5

Despite these what ifs potentially making little difference in the result of the battle, what about death and night stealing victory from the Confederates? Of all the questions that the soldiers of the battle as well as historians and buffs ever since have debated, Johnston’s death and the stoppage of the Confederate advance at night have emerged as the key explanations causing defeat for the Confederates at Shiloh. But did they?6

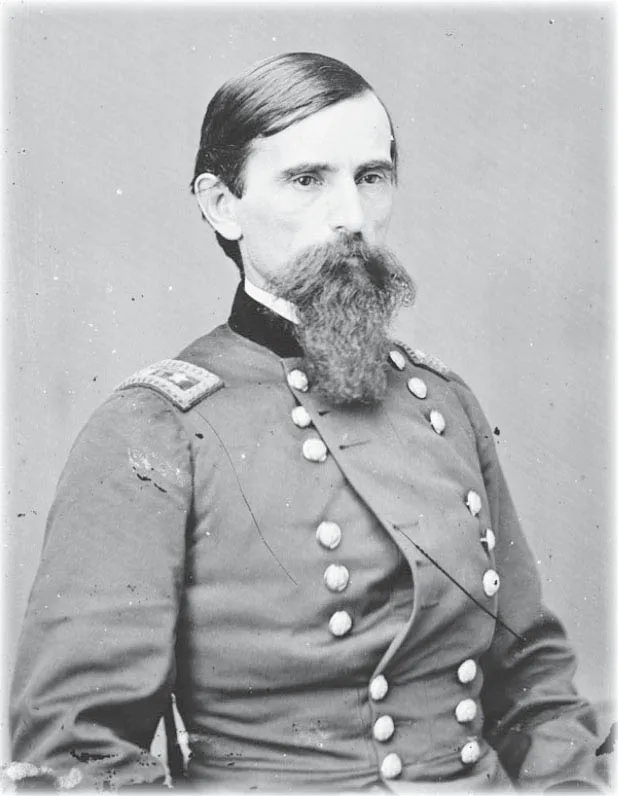

The effect of Albert Sidney Johnston’s death has long been a source of debate. Participants in the battle itself first made claims as to whether his death affected the outcome, and the major actors in the debate, or in the deceased Johnston’s case his son, succinctly analyzed both arguments in major articles that appeared primarily and most concisely in the famed Century (Battles and Leaders) series of publications in the 1880s.7

The arguments are plain on the surface. Johnston’s son, William Preston Johnston who was later an aide to Jefferson Davis in Richmond, argued that his father was on the verge of victory at 2:30 p.m. when he bled to death. Johnston had moved to the right of the Confederate line, where the all-important turning movement around the Union left flank was to occur. Because the right flank was stalled, Johnston determined he had to put his substantial leadership abilities in the fight and lead from the front. It worked, at least on the isolated tactical level at the time, and the charge Johnston led in part moved the Union line rearward through the Peach Orchard area.8

After Shiloh, the Confederacy suffered from command problems in the western theater for the rest of the war, from incompetent leadership to infighting. Win or lose, what if Albert Sidney Johnston had lived beyond the battle of Shiloh? Chris Mackowski

Unfortunately, during the advance Johnston took a bullet in the right leg just behind the knee and in the course of thirty minutes or so bled to death right on the battlefield. A simple tourniquet could potentially have saved his life, but Johnston probably did not even know he was wounded until far too late. And, his staff surgeon, D. W. Yandell, had been left in the rear to care for wounded in some of the Union camps. The result was that Johnston perished in a ravine behind the lines, his call to conquer or perish having become partly true as Johnston perished in the attempt. Whether the conquer part would fade would be up to his successor in command of the army, General P. G. T. Beauregard.9

Shiloh Argument over what would have happened if Albert Sidney Johnston had lived at Shiloh has raged since the afternoon he died. Having put the Confederate army in motion and attacking on the morning of April 6, 1862, Johnston perished in the early afternoon, a result of bleeding to death because an artery in his leg had been hit. Many historians have argued that Johnston was in the process of winning the victory at the time of his death but that his successor, P. G. T. Beauregard, threw away Johnston’s victory when he called off the final assaults on the Union last line of defense nearer to Pittsburg Landing. In reality, Beauregard continued Johnston’s push forward after the army commander’s death—even faster that Johnston had been pushing, in fact— and managed to neutralize the famed Hornet’s Nest, something Johnston had failed to do throughout the day. And Beauregard’s final recall order stopping the attack came when Confederates at the front, on the ground itself, had already come to the same conclusion and were themselves stopping the attacks on their own. Beauregard did not throw away Johnston’s victory, which Johnston was not actually winning when he died. As a result, the “what if” of Johnston living would have made no appreciable difference in the outcome of the Battle of Shiloh.

William Preston Johnston argued that his father was on the verge of victory, the successful charge he had just led a case in point. He made elaborate arguments in both his article for Battle and Leaders as well as a lengthy biography of his father published in 1879. It was there that he argued that his father died at the height of victory but that Beauregard took the reins of command and promptly threw away the hard earned success. He wrote that up until his father’s death there was “the predominance of intelligent design; a master mind, keeping in clear view its purpose.” This argument, of course, made its way into the UDC monument at Shiloh, where Johnston’s bust figured prominently on the center front and where the veiled figure of death (Johnston’s) snatched the laurel wreath of victory from the South. Illustrating the importance of Joh...