![]()

100 grams to 1 kilo (2.2 pounds)

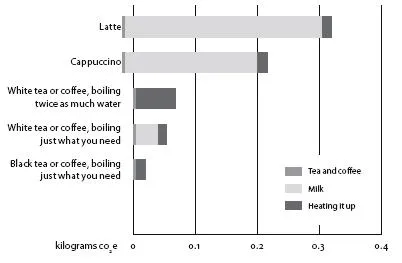

A mug of tea or coffee

23 g CO2e black tea or coffee, boiling only what you need

55 g CO2e with milk, boiling only what you need

74 g CO2e average, with milk, boiling double the water you need

236 g CO2e a large cappuccino

343 g CO2e a large latte

So if you drink four mugs of tea with milk per day, boiling just what you need, that’s the same as a 60-mile drive per year in an average car. A single latte every day would be nearly 1 percent of the 10-ton lifestyle.

The shock here is the milk. If you take tea or coffee with milk, and you boil only the water you need, then the milk accounts for two-thirds of the total footprint (see Milk). The obvious way to slash the footprint of your tea is reduce the amount of milk, or simply to take it black (herbal tea, anyone?) (Figure 4.1). Although this will reduce your nutritional intake, you could easily replace the lost calories with something more carbon friendly such as a biscuit.

I have based my cappuccino and latte sums on the large kind that some of the coffee-house chains encourage you to quaff. These come in with a higher impact than four or five carefully made Americanos, filter coffees, or teas. They also mean you are drinking an extra cup of milk, perhaps without realizing it.

FIGURE 4.1: The footprint of one cup of tea or coffee with no sugar.

At my work we’ve suddenly decided that next week we’re all going to do without milk in our drinks. At worst it will taste horrible. At best we’ll change habits of a lifetime, resulting in decades of reduced hassle, lower carbon, slight cost savings, and possibly even fractionally improved health. It has to be worth trying.*

If you boil more water than you need (as most people do), you could easily add 20 g CO2e to your drink. Boiling more than you need wastes time, money, and carbon; if you haven’t yet developed perfect judgment, to avoid this you can simply measure the water into the kettle by using a mug.

Finally, think about your mugs. Buy sturdy ones; look after them and save hot water by only washing them up at the end of the day, rather than using a fresh mug for every cup.

A mile by bus

15 g CO2e one of 20 passengers squeezed into a minibus in the suburbs of La Paz

150 g CO2e typical city bus passenger

The efficiency of a bus is just about proportional to the number of people it is carrying. It also depends on the amount of stopping and starting.

La Paz, Bolivia, is the place I think of where this principle is practiced to perfection provided you are prepared to set aside a bit of safety and comfort. Twelve-seater minibuses charge around town with 20 or more people crammed inside. You can get just about anywhere for one Boliviano—a few cents—and you are unlucky if you have to wait more than 5 minutes. Most people in the developed world would choose a luxury version of this for perhaps five times the price, but the principle is sound, and in Bolivia 10 years ago the “value proposition” met the market need perfectly.

All my numbers have factored in the fuel supply chains as well as the exhaust pipe emissions. I also include a component for the emissions entailed in manufacturing the vehicle, although for the bus this is a small consideration because they do so many miles before needing replacement.1

A diaper

89 g CO2e reusable, line-dried, washed at 60°C (140°F) in a large load, passed on to a second child

145 g CO2e disposable

280 g CO2e reusable, tumble-dried and washed at 90°C (190°F)

> So that’s 550 kg (1,200 lbs.) per child for two and a half years in disposables, the equivalent of nearly two and a half thousand large cappuccinos.

Most parents will be relieved to hear that there is usually no carbon advantage to be had from reusable diapers. On average they come out slightly worse, at 570 kg (1,250 lbs.) per child compared with 550 kg (1,200 lbs.) for disposables. And if you wash them very hot and tumble-dry them, reusables can be the worst option of all. However, if you put your mind to it, you can make reusables the lowest-carbon option. To do this, pass them on from child to child (so that the emissions embedded in the cotton are spread out more), wash them at a lower temperature (60°C/140°F), hang them out to dry on the line, and wash them in large loads.

For a disposable diaper, most of the footprint comes from its production. But about 15 percent arises from the methane emitted as its contents rot down in landfill (contrary to the myth that if you wrap them up in a plastic bag they will never rot at all).

The study I’m basing my figures on assumed that the average child stays in diapers for about two and a half years and is changed just over four times a day.2 On this basis, in the U.K., diapers account for something like one two-thousandth of total greenhouse gas emissions—or more like half a percent for homes with babies.

What does all this mean for the carbon-conscious family? If you have two children and stick to non-tumble-dried reusables throughout, you might be able to save nearly half a ton CO2e. You will also cut out landfill. It’s a significant efficiency, but (here’s the catch) you need to know your own minds before you start out because if you give up, revert to disposables and trash the reusables, it could be the option with the highest footprint of all. But try to keep all of this in perspective: if you take just one family holiday by plane, you will undo the carbon savings of perfect diaper practice many times over.

When he was the U.K.’s climate change secretary, Ed Miliband recently drew on the same diaper study to defend his announcement that his own children wear disposables. He was roasted—somewhat unfairly I thought—by blogging eco-mums who claimed that the study was fatally flawed. Poor chap. At least he’d thought about it. The debate illustrates, yet again, that this kind of analysis is more murky and subjective than we might think.

A basket of strawberries

150 g CO2e (or 600 g per kilo/270 g per pound) grown in season in your own country

1.8 kg CO2e (or 7.2 kg per kilo/3.3 kg per pound) grown out of season and flown in, or grown locally in a hothouse

> How have we got into the habit of buying tasteless out-of-season strawberries, which have a footprint more than 10 times the tastier seasonal version?

Although I’ve given just one number for local, seasonal strawberries, the precise footprint depends on such things as the soil, the use of fertilizer and the use of polytunnels.3 Some of these variables increase both the yield and the emissions per acre, so whether they result in more or less carbon per strawberry is not so simple to work out. Luckily, they are all so much better than the out-of-season version that a good enough rule of thumb is just to stick to those grown in your own country—unless your government subsidizes the heating of greenhouses (as is the case, for example, in the Netherlands). This kind of hot-housing is, broadly speaking, just as bad as air-freighting the fruit from hotter countries (see Flying, and Asparagus).

In short, then, the best advice is to wait until they are in season, then enjoy them twice as much. Or if you really can’t wait, buy frozen or tinned: these lie somewhere in the middle ...