![]()

1

The Silent Screen, 1895–1927

Cecil B. DeMille Shapes the Director’s Role

Charlie Keil

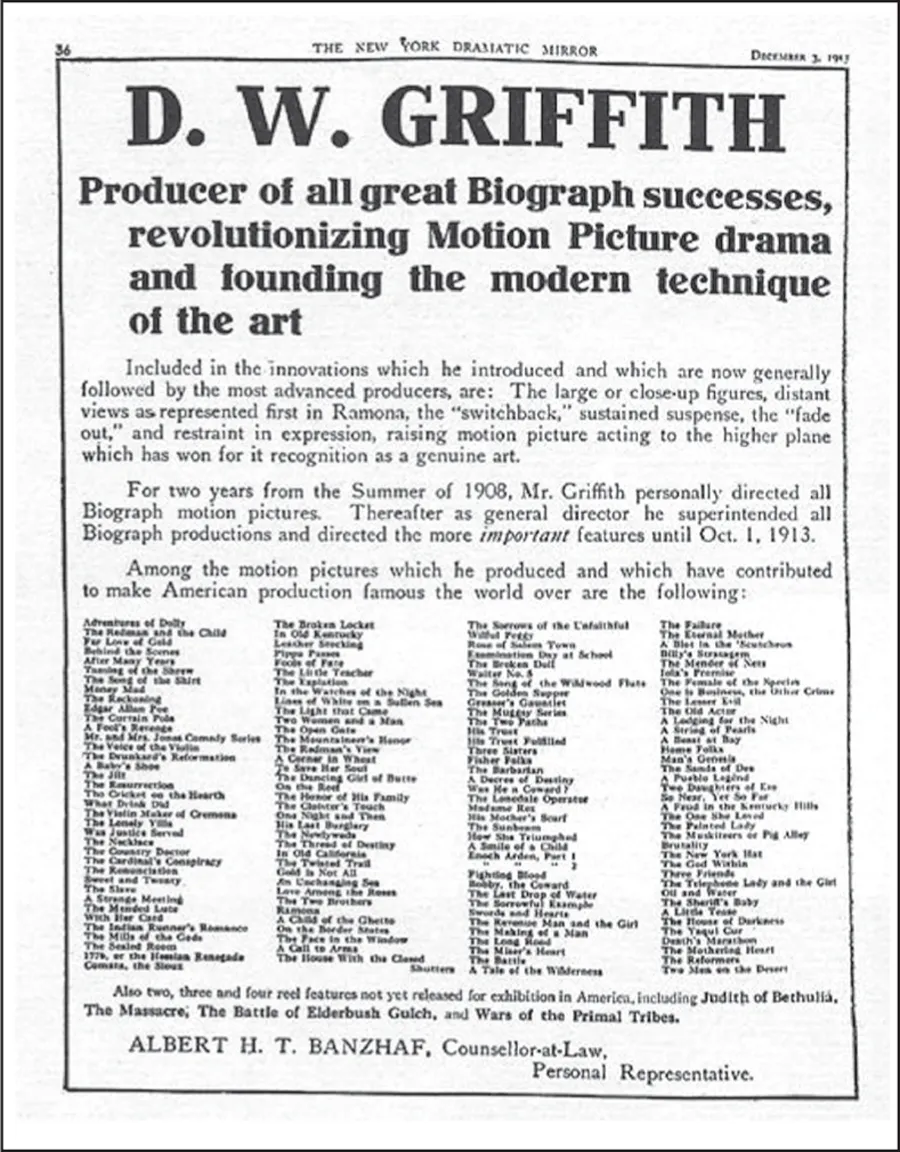

When Cecil B. DeMille directed his first film, The Squaw Man, in 1913, the American film industry was at a turning point, marked by the convergence of a number of significant developments, among them the advent of the feature film, the shift to West Coast production, and attendant changes to the organizational processes governing how movies were made. Nineteen thirteen was also the year that D. W. Griffith ran an advertisement in the New York Dramatic Mirror, trumpeting his indelible contributions to cinema by declaring himself responsible for “revolutionizing Motion Picture drama and founding the modern technique of the art.”1 Griffith made a case for his status as the preeminent film artist in the United States by staking out the terrain of cinematic style and laying claim to every device imaginable, from the close-up to crosscutting. Moreover, Griffith asserted his singular achievements by arguing that all of the innovations that he had introduced were “now generally followed by the most advanced producers.”2

I dwell on Griffith’s self-promotional advertisement not to make a case for his uncontestable mastery of the medium by 1913, nor even to suggest that the ad helped cement his status as the most famous filmmaker at work in the American film industry, though he may well have been so. Instead, I enlist this document to reinforce the idea that 1913 was a pivotal time for both the institutionalization of cinema and, consequently, the successful marketing of the idea of the director function. In other words, Griffith’s attempt to define himself as a film artist would scarcely have had any traction had that effort not possessed some value within the burgeoning industry at this time. (To verify this conclusion, one need only point out that up to this moment Griffith had remained unidentified by his former employer, Biograph, and that the ad operated as a way for Griffith to set his market value when selling his talent to the next company interested in hiring him.)

FIGURE 4: The 1913 New York Dramatic Mirror advertisement that publicly established D. W. Griffith’s credentials as a director of motion pictures.

In 1913, then, Griffith was not only attempting to secure his authorial legend, he was also helping to define the terms by which the still rather nebulous position of film director might be understood. (One should note, for example, that the ad tends to use the verbs “directing” and “producing” almost interchangeably.) For its maximal utility, the potential of the position had to be registered by both the film industry and moviegoing public alike, so the Griffith ad operates as a form of tutelage, no matter how self-serving. Soon enough, the industry itself would also influence how the public might perceive the director function, at the same time that it would set more firmly the parameters for the roles that directors would perform within developing studio practices. Coincident with the move to the West Coast and the wide-scale manufacturing of features, the industry progressively embraced a production model dependent on the rationalization of labor; concurrently, individual companies gained increased power and public recognition through enhanced levels of publicity and promotion, of both film texts and contracted personnel.

If Griffith established a particular template for defining the director in his Mirror advertisement, one predicated on innovation and influence, it proved less of a signpost for the industry as a whole than its singularity at the moment of 1913 might suggest. The molding of the director function occurred as it was put into practice by the budding studio system, and that process did not rest within the control of a maverick like Griffith. The director function operated as part of a more expansive corporate strategy, in much the same way that the director as worker had to operate within the broader machinations of the nascent studios. No individual director of the 1910s could possess sufficient power to shape how studios came to define the role.

But here is where Cecil B. DeMille, the figure whose directorial debut served as the starting point of this chapter, reenters the narrative. For a variety of reasons, DeMille, who quickly established himself as both an artistic and commercial success by the mid-teens, crafted a career that serves as a more likely model for the usefulness of the director function to the industry. Most obviously, DeMille’s facility in wedding melodramatic narrative formulae to a self-consciously inventive approach to lighting, staging, and editing seemingly demonstrated how a director could be an artistic benefit to a studio without the concomitant burden of becoming an economic liability. By emerging as a stylistically distinctive but profitable director, DeMille helped demonstrate the salability of the director function for an industry embracing new methods of production and distribution during the 1910s. As Gaylyn Studlar has observed, DeMille was gathering steam just as studios were “economically motivated to look for means [beyond stars] of securing the loyalty of motion-picture audiences . . . and audience expectations of a predictably enjoyable moviegoing experience depended upon [a] director establishing a solid record of favorably received films.”3

DeMille’s status as a crucial figure in our understanding of the film industry’s moves to define the director function during the 1910s extends beyond his mere marketability. Even more important may be his role as a studio executive during this period. Heading the Hollywood branch of Famous Players–Lasky for the first half-dozen years of his career, DeMille had to balance running a fledgling studio with the effort to define himself as an identifiable director in the public’s mind. Arguably, this experience helped to clarify for DeMille what the role of a director could be at the very time that the parameters of this vital creative position were still in formation. The years prior to 1913 represent a period where the director slowly gained prominence within the production process; DeMille’s seminal experiences as a hyphenate studio-executive/director in the mid- to late 1910s demonstrate how the studios embraced the director function as part of a broader strategy of industrial expansion. Moreover, DeMille himself came to recognize how he might exploit the role for his own career advancement. Cecil B. DeMille proved integral to the hierarchical conception of the director function that was devised during the 1910s, a conception that became as stratified as the star system that emerged at the same time.

Early American Cinema and the Shifting Role of the Director

Changing conceptions of the director function are directly tied to evolving modes of production within the early American film industry. During the years that I have labeled the transitional period (from 1907 to 1913), effective storytelling became the primary goal of film producers; ultimately, the focus on intelligible stories, conveyed in a manner that would keep an audience involved in the narrative, put additional onus on the screenplay and the role of the director in translating that script to screen.4 Prior to 1907, an emphasis on the camera operator’s centrality to the production process had meant that the role of the director (such as it existed) received significantly less attention. Accordingly, the director function was often subsumed within the responsibilities of the camera operator. Whether one subscribes to the “cameraman system” model of production described by Janet Staiger or the “collaborative system” preferred by Charles Musser,5 one comes to the conclusion that directors did not consistently perform a clearly demarcated role within producing practices used for fiction filmmaking in the pre-1907 period. Typically the camera operator assumed primacy in the filming situation, not only controlling all the technological aspects (including lens choice and camera positioning), but also staging and coaching the actors. If, within the collaborative system, duties were not simply shared but split, one of the collaborators might well assume the responsibilities commonly associated with a theatrical director, leaving other, more technical tasks for his counterpart; this arrangement, according to Musser, typified the films made at Edison by George S. Fleming (an actor and scenic designer) and Edwin S. Porter (a cameraman).6 Tellingly, Porter is the figure now identified as the “director” of the films that the pair made for the company, indicating that the cameraman remained the dominant creative figure for films produced before 1907.

Staiger and Musser also differ in their respective preferred typologies for production systems employed after 1907, with Staiger opting for “the director system” to name the method adopted in 1907–1909, and then “the director-unit system” for that prevalent until 1914.7 Musser, on the other hand, argues that a “central producer system”—which Staiger says did not become dominant until 1914—came into use as early as 1907.8 Staiger’s choice of the term “director system” is telling, as it signals the ascendancy of the director in the production hierarchy, though she concedes that “the terms ‘producer’ and ‘director’ were even used synonymously.”9 Staiger stresses that the role of the film director was patterned after that of the stage director, a function that had emerged within the context of modern theater in the 1870s. Such a model seemed appropriate for American cinema as it embraced narrative, and, as Staiger points out, many of the film directors who would gain prominence over the next few years, Griffith, Sidney Olcott, and Herbert Brenon among them, came from the stage, though usually their training had been in acting. In the director system, the director oversaw all stages of a film’s production (and even postproduction), with most distinct tasks (such as cinematography, set construction, and scenario writing) undertaken by designated craftspeople under the explicit supervision of the director.

What both Staiger and Musser identify as the need for more product (demand coming from the rapidly expanding exhibition sector) hastened the introduction of new production systems that accorded the director more authority within an increasingly hierarchical division of labor. And despite their use of different terminology, they concur that, to use Musser’s words, “the process of reorganization favored the increased authority of the director . . . [as] areas of directorial responsibility were expanding.”10 As Musser points out, the director function was best positioned to make optimal use of the stock companies of actors that most manufacturers were now establishing to meet the increased production rates. With scenarios gravitating progressively toward character-centered narratives, the contributions of the actor gained more importance. And, as the figure responsible for the actors’ performances, the director moved into a position of prominence within the production chain of command.

Directors enjoyed varying degrees of autonomy during this transitional period, as companies vied to make compelling story films that would please audiences and convince exhibitors of the value of a specific company’s output. While the production process was becoming increasingly hierarchical, the controlling influence of a central producer varied from studio to studio and from one shooting situation to the next. At Biograph, Griffith functioned as both producer and director, which meant that he could oversee the editing of his films, whereas directors at other companies (such as Edison) ceded that responsibility to a supervising producer. Despite the indisputably important role that the director performed within the production process, few companies afforded the director the near-complete autonomy that Griffith enjoyed (precisely because few directors also functioned as producers for their companies). Instead, the development of a central-producer model meant that directors would perform circumscribed tasks within a broader system of production. Tellingly, they remained anonymous workers for the majority of the transitional period; with most films from these years lacking credits, few clues exist as to the identity of the directors, let alone their respective contributions.

The very anonymity of so many directors during the transitional period raises intriguing questions about how one attributes any associated authorial properties of the director function to seemingly “unauthored texts.”11 Griffith has become a privileged figure within histories of stylistic development during this period in large part because we know which films he directed. (Beyond that, nearly all of his films from the era have been preserved.) What Tom Gunning has defined as the “narrator system”—a type of visual discourse devised to maximize the effective representation of the dramatic situations at the core of this period’s scenarios—can certainly be linked to Griffith’s distinctive achievements in editing, framing, cultivating strong performances, and other aspects of film style. But Gunning also ...