![]()

Chapter 1: The Honduran Reforma: The State, Economic Structure, and Class Formation, 1870S–1940S

“Nations,” Eric J. Hobsbawm has argued, “do not make states and nationalisms but the other way around.”1 In Honduras the formation of the modern state as the basis of nation building began in the 1820s, but the process did not assume strength until well after the 1870s. Numerous problems confronted nation builders after independence in 1821. Most of these difficulties originated in the colonial period and only intensified between the 1820s and the 1870s. Honduras emerged from this period with a specific economic structure whose connections to the world economy affected the country’s different geographic regions rather distinctively. The Honduran North Coast slowly accumulated a social and political prominence intimately associated with the peculiarities of the region’s geography and class structure.

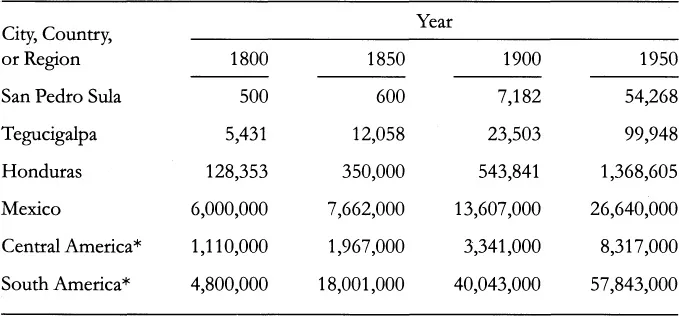

In the 1820s the Honduran population amounted to about 130,000, of which an estimated 60,000 were indigenous inhabitants recovering from their demographic collapse in the sixteenth century (see Table 1.1). Then, the indigenous population amounted to about 800,000. The negro, mulato, pardo, and zambo populations of Honduras seem not to have been large, and most apparently lived on the North Coast.2

During the colonial period Honduras remained a province of the Captaincy General of Guatemala, itself administered by Mexico. Contemporary Central America emerged as a formally unified nation in the 1820s. In 1821 creoles of the Captaincy General declared their independence from Spain, frankly acknowledging that they took the step to “prevent the dreadful consequences resulting in case Independence was proclaimed by the people themselves.”3

Table 1.1. Estimated Population of San Pedro Sula, Tegucigalpa, Honduras, Mexico, and Central and South America, Selected Years, 1800–1950

Sources: Pastor Fasquelle, Biografía, pp. 13, 142; Dirección General de Estadística y Censos, Honduras: Histórica-Geográfica, pp. 115, 323; Guevara-Escudero, “Nineteenth-Century Honduras,” pp. 84, 166, 178, 183; Sánchez-Albornoz, “The Population of Colonial Spanish America,” p. 34, and “The Population of Latin America,” p. 122; Furtado, Economic Development of Latin America, p. 12.

*Central America excludes Belize and Panama. South America includes all the present officially Spanish speaking countries of the mainland continent. San Pedro Sula’s figures for 1800, 1850, and 1900 are for 1801, 1860, and 1901 respectively. Tegucigalpa’s figures for 1800 and 1850 are for 1801 and 1855 respectively. Central America’s figure for 1800 includes Panama and the state of Chiapas, in Mexico.

NATION BUILDING BEFORE THE 1870S

Nation-state building in Honduras became a chaotic process. From 1821 to 1838 Honduras remained a province of a Central American nation, a nation for which creole leaders, as in the rest of postcolonial Latin America, tried desperately to establish and consolidate a state that might actually give this new nation a reality beyond the paper on which it was outlined.4 Between the 1830s and 1870s Honduran governments remained very unstable, constantly oppressed by civil wars and military movements and threats, thus incapable of consolidating a central state. In fact, from the 1820s to 1876, chief executives averaged only about 6.5 months in power.5 The nature and intensity of these conflicts originated in the late colonial period.

Between the 1770s and the 1820s Honduran creoles enjoyed three basic sources of wealth: a tobacco factory near the provincial capital of Comayagua, silver ores exploited near Tegucigalpa, and the domestic cattle market. Unfortunately, these exports collapsed early in the nineteenth century. The dynamic behind growth and stagnation in the late eighteenth century lay with the European demand for Salvadoran and Guatemalan indigo. Cash from indigo stimulated the other economies. But from the 1790s to the early 1800s war in Europe interrupted indigo marketing, and, worse, locusts attacked the crop itself. Moreover, indigo exports from Venezuela and indigo imports to England from Bengal further damaged indigo’s role vis-à-vis the Central American economy.6 Civil wars during the 1820s and 1830s aggravated the collapse.

These problems did not disappear with independence. Indeed, “the new nation was born in debt.” In 1821 the treasury recognized outstanding obligations amounting to over four million pesos, a sum that increased to about five million after independence from Mexico. Soon more loans were assumed. In 1825 Central American federal governments contracted loans in British financial markets.7 By 1826 the first loan succumbed to a British stock market collapse, and the Central American government was saddled with debts largely for expenses, commissions, government salaries, and cash advances. The collapsing regional economies and civil wars did not help in obtaining resources to pay the bills that accumulated into the 1860s, long after 1838, when Honduras separated from the Central American Federation.

The Honduran economy before the 1870s could little afford to sustain a strong, centralizing state. During this period three commodities alternated as Honduras’s most profitable exports: cattle, hardwoods, and mineral products, mainly silver and gold. Exports of cattle, hardwoods, and mineral products beyond Central America stimulated commercial growth in certain areas of the territory and during given periods: cattle to the Caribbean, especially to Cuba (1850s–80s); hardwoods to Great Britain via Belize (1840s–70s); and gold (1830s–40s) and especially silver (1850s–70s) to England and the United States.8

Yet fiscal revenues from these exports never energized the state. The fact is that economic relations connecting Honduras and world markets from the 1830s to the 1870s did not sustain a state capable of producing the “nation” imagined by elite Hondurans. A different history occurred between the 1870s and 1940s.

LIBERAL REFORM IN HONDURAS

In July 1877 U.S. Consul Frank E. Frye, stationed on the North Coast of Honduras, informed the U.S. Department of State that the recently empowered liberal Marco Aurelio Soto seemed determined to carry out a “thorough regeneration of the country.” Soto and his followers received military support from the Guatemalan liberal general Justo Rufino Barrios, and on that basis Honduran liberals set out to incorporate the country into a newly vibrant world economy and imagine a new nation. Consul Frye did not misunderstand Soto’s objectives. Earlier, in October 1876, Ramón Rosa, Soto’s cousin and closest adviser, had promised a “radical change in the way of seeing, representing, and serving the rights and interests of the nation.”9

The new regime confronted the questions of nation-state formation directly.10 In a speech to Congress in 1877, Soto described reforms that emphasized commercial agriculture as the major economic sector on which to base the country’s “regeneration,” but he did not mention banana cultivation as a priority. Legislation that April only offered incentives for commercializing agriculture generally. In the mid-1870s banana markets seemed unimportant. Coastal regions did not yet report major profits in banana cultivation. Soto and Rosa imposed new duties only on the thriving Bay Island commerce in 1879. Authorities taxed only banana exports in 1893, when the Department of Cortés was finally created. However, local regional authorities saw a different situation. In 1898 San Pedro Sula, the North Coast’s leading town at the time, made banana cultivation its official patrimony.11

In the early 1880s Soto and Rosa concentrated on reforms necessary to create a state that might support commercial agriculture as a whole, especially road construction. But a financial crisis throughout this period prevented investment in a national road-building program. The carretera del norte from Tegucigalpa to San Pedro Sula reached its halfway point only in 1918.12

Authorities paralleled road development with efforts to refurbish fifty-seven miles of railroad that extended from the port of Puerto Cortés to San Pedro Sula, both in the Department of Cortés. Soto hoped to use this “Inter-oceanic Railroad” to integrate the region’s economic development and secure revenues to pay a massive foreign debt assumed in order to build these few miles. Negotiations concerning the railroad dated back to the 1850s. U.S. investors and Honduran governments projected a railroad that might cross Honduras, pass through Tegucigalpa, and end in a Pacific port in the Bay of Fonseca. Between 1867 and 1870 Honduran governments negotiated loans in French and British financial markets, but the project failed utterly.13

Corruption in Honduras and in Europe reached impressive proportions. Little of the negotiated funds made it to Honduras. Contractors built the fifty-seven miles available to Soto in the 1870s, and the loans continued to accumulate. In 1888 “one observer calculated the debt at twelve million pounds” while also noting that at “prevailing land values, Honduras could not repay such a debt by selling its entire national territory.” Honduran and British officials did not sign an agreement resolving the matter until the mid-1920s. Honduras finished paying the debt in 1953.14

In 1876 Soto reclaimed the railroad and operated it for his government’s benefit. In 1879, short on funds and personnel, he granted U.S. investors an exclusive ninety-nine-year concessionary contract to develop the railroad, build ports, obtain land, exploit mines, and deal with the debt claimed by the British. The venture faltered and a notorious legacy was established. By the 1890s the Cortés Interoceanic Railroad fell under the control of Washington S. Valentine, a U.S. mining tycoon operating near Tegucigalpa.15

SILVER AND BANANAS: PRELUDE TO THE FATE OF COFFEE

Did Soto and Rosa’s incentives to export lumber and cattle provide the basis for the wealth of a Honduran oligarchy? What about tobacco and sugar?16 What happened to coffee, the prime export elsewhere in Central America and the inspiration for liberal reformers in Honduras? Rosa’s dream never materialized, and late in life he was keenly aware of the impediments. By the late 1880s silver, owned primarily by foreign companies, became the major export originating in Honduras, mostly in the interior. Mining companies rarely located on the North Coast.17

Direct foreign investment in Honduras between the 1870s and 1890 was small, and it did not grow much even in the first decade of this century. In 1897 and again in 1908 the U.S. DFI amounted to only $2 million. It soared during the next two decades, amounting to $9.5 million in 1914 and $18.4 million in 1919.18 These investments went mostly into the banana exporting industry controlled by U.S. capital. First, however, foreign investors took control of the most important mineral exporting companies, a critical issue often marginalized in discussions of the so-called Banana Republic.

The most profitable companies, especially Washington S. Valentine’s New York and Honduras Rosario Mining Company in silver, exploited mines near Tegucigalpa, within a southeastern radius of ten to sixty miles from the city. The economic significance of this foreign investment remained limited to that area, where laborers for the mining companies rarely exceeded 1,500 workers even in the 1940s. In the 1910s and 1920s the annual employment by foreign banana companies often amounted to ten or fifteen times employment by the mining industry of the interior.

Tegucigalpa’s population increased from about 12,000 in 1881 to about 24,000 by 1901. But the consequences for cementing the process of state formation on a national scale was minimal. Despite a “boom” recorded after the early 1880s, the import and export dollar values registered in 1900 only equaled the figures registered in 1880. Data for Honduran mineral exports for this period show that export values remained stable but limited, with the value of banana exports quickly surpassing that of mineral exports by the early 1900s, particularly after the 1910s.19

It is evident that state revenues did not secure any tax base from even the few companies that eventually initiated mineral exploitation or from those that actually profited greatly, particularly the New York and Honduras Rosario Mining Company. By executive decree and by concessions, companies did not pay import duties on mining machinery, nor did they pay taxes on mineral exports.20 Also, most of the influential companies generally avoided paying municipal taxes, either by manipulating or cajoli...