FIVE

“ALL RISE!”

On the morning of January 11, 2000, the lawyers, solicitors, paralegals, experts, and researchers gathered in Rampton’s chambers. There was a palpable energy in the room. Rampton wore his special QC court dress—a silk vest and a jacket ornamented with horizontal braids. He busily inspected some files. Heather Rogers, in her frilly barrister’s white shirt and black suit, consulted with the researchers. The solicitors conversed with one another as the paralegals answered the incessantly ringing mobile phones. When the clock struck ten, Rampton looked up and declared, “It’s time.” Having anticipated this day for over four years, I felt like an Olympic runner walking to the track, ready to best my opponent.

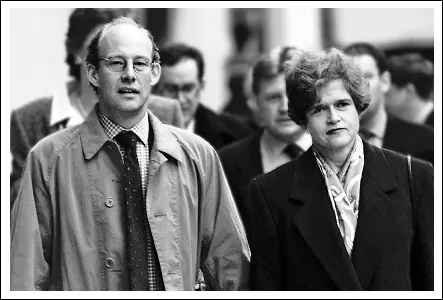

Penguin lawyers had suggested that the legal team and I walk shoulder to shoulder along the three-hundred-yard journey from Brick Court to the courtroom on Fleet Street as a gesture of author/publisher cooperation and commitment in this ordeal. Anthony Forbes-Watson, Penguin’s managing director, and I fell into step next to each other, with lawyers, experts, and researchers walking behind us. Emerging into the bustle of the street, I spotted a horde of paparazzi in front of the building. We approached from the east end of the street while they were looking west, closely watching passengers emerging from taxis. No one spotted us until a photographer crouching down on one knee glanced over his shoulder in our direction. “Here she comes!” he screamed out, his colleagues turning in one fell swoop. While oversized zoom lenses trained on me, I tried my best to exude confidence. As we approached the entrance, a gaggle of photographers blocked our way, calling out, “Madam, look this way,” or, “No, this way.” They kept asking for a statement, and the more I declined, the more they insisted that I comment on what it felt like to be at the center of this controversy.

The Royal Courts of Justice—known to Londoners as “The Law Courts”—is an enormous building with spires, clock tower, steepled buttresses, ornamental moldings, and statues of Jesus, Solomon, King Alfred, and a host of bishops. It dominates the busy London intersection where Fleet Street meets the Strand. In QBVII, Leon Uris aptly described it as “neo-Gothic, neo-monastic, and neo-Victorian.” Despite its architectural hodgepodge, it is impressive. The 250-foot-long Gothic entry hall is a cross between a large medieval church and a grand nineteenth-century railway station. Its massive vaulted ceiling soars 80 feet in height. Stone benches set into the wall, line the length of the hall. Above them are stained glass windows with the coats of arms of England’s lord chancellors. A large clock hangs from an upper level balcony and is visible from every point in the hall.

Over the years, extensions have been added to the main building. Now many of the courtrooms are reached through vaulted passageways, meandering corridors, and small courtyards. As I followed the lawyers, I felt as if I was moving through a maze within a labyrinth, which seemed—given what I was about to face—an appropriate metaphor. I could hear commotion near the courtroom. People were trying to convince the court ushers to let them into the room, which was already filled to capacity. As we pushed our way through, the crowd began to grumble, as if presuming that we were jumping the queue until someone pointed out that I was the defendant. The courtroom, in contrast to the building, was relatively modern. There were three rows of tables. A front-row seat had been reserved for me between James and Penguin’s solicitors. Those permitted to speak in court—Rampton, Heather, and Anthony—sat in the second row. Irving, acting as his own barrister, would sit at the far end of that row. In front the court stenographer was arranging her equipment. Her transcriptions would appear simultaneously on the computers that had been placed on the tables.

One entire wall of the room was filled with bright red and blue loose-leaf binders containing a copy of every document or piece of evidence referred to in the expert reports. In a throwback to previous centuries each binder is called a “bundle.” When I first heard the term, I imagined the documents would be brought to court tied up with string. Chairs along the far wall had been reserved for the press. At the back of the room were a couple of rows of seats for the public. Some of these were occupied by my supporters. A year earlier my friend Ursula Blumenthal, whose husband, David, is my Emory colleague, announced, “When the trial begins, we’ll be there.” At the time I insisted that I didn’t want anyone there, though I’m not sure why. Perhaps I feared that Irving’s attacks on me would be too unpleasant for them to witness. Luckily they ignored my protestations because now, as this saga commenced, being alone seemed unfathomable. Ken Stern, who had dropped his other work at the American Jewish Committee to attend, was there as well. Grace, the art curator who had sent me to the Assyrian exhibit, had come from Los Angeles. Bruce Soll, counsel to Leslie Wexner, had arrived that morning from Columbus.

Irving entered carrying a large stack of books under his arm. He was wearing the same dark blue pin-striped suit that he had worn to the pretrial hearing. He stood alone, surrounded by empty chairs, which, under normal circumstances, would have been occupied by his legal team. He had told journalists that he had elected to represent himself because this battle concerned his area of specialization. He had, he contended, an advantage over lawyers. They might know the law, but he knew the topic.

The usher’s pronouncement—“Silence. All rise”—brought everyone to their feet as a bewigged Judge Charles Gray entered the room. Everyone bowed slightly. He returned the gesture and we sat down. His dark silk robe, trimmed at the cuffs and neck with white ermine, and the red satin sash across his neck harkened back to another era. Judge Gray sat on the upper level of a two-tiered judge’s bench that dominated the front of the room, so high above me that I had to crane my neck to see him. Peering out at the packed courtroom, he apologized that not all who wished to be here could be accommodated and promised to seek a larger site.

BRANDED WITH A YELLOW STAR

Irving began by addressing procedural issues. Prior to the trial, Irving and Rampton had agreed that the questions relating to Auschwitz would be dealt with as a separate issue. Irving assumed that this would come at the very end of the trial, which would give him more time to prepare. Rampton, on the other hand, thought the Auschwitz phase would be at the end of January when Robert Jan was scheduled to arrive. After a bit of debate, Irving conceded that he was “perfectly prepared to have Professor van Pelt come over in the middle of whatever else is going on and we can take him as a separate entirety.”1

With that settled, it was time for opening speeches. Irving, as the plaintiff, was to speak first. All eyes were on him as he slowly and deliberately arranged his papers on the small podium. He was, he began, not a Holocaust denier. In fact, he argued, he should be credited for drawing attention to the Holocaust by “selflessly” publicizing historical documents he had uncovered in various archives and collections. Then, ignoring the fact that he initiated this case, he declared, “If we were to seek a title for this libel action, I would venture to suggest, Pictures at an Execution—my execution.” There was a time, he told the court, when his books would annually earn more than £100,000. When his accountant asked what steps he had taken in anticipation of retirement, he said, “my immodest reply was that I did not intend to retire. . . . my books were my pension fund.” He expected his royalties to sustain him “beyond the years of retirement.” Knowing he lived in Mayfair, one of London’s tonier neighborhoods, and having seen, many years earlier, a picture of him climbing into his Rolls-Royce, I assumed that this was indeed correct. That, he claimed, was no longer the case. His career had been torpedoed. Gesturing in my direction, he accused me of being responsible. “By virtue of the activities of the Defendants, in particular of the Second Defendant, and of those who funded her and guided her hand, I have since 1996 seen one fearful publisher after another falling away from me, declining to reprint my works, refusing to accept new commissions and turning their back on me when I approach.” I had done this, he continued, as “part of an organized international endeavor.”2

He promised to expose our nefarious scheme. “I have seen the papers. I have copies of the documents. I shall show them to this court, I know they did it and I now know why.” Barely pausing for breath, he whipped off his glasses and accused me of having branded him with a “verbal Yellow Star” by calling him a denier. As a result he was now treated like a “wife beater or a paedophile.”3 Though I expected that he would depict himself as the victim, I was surprised by his selection of the yellow star as the symbol of his professed predicament. I had anticipated that, at least in the courtroom, Irving would modulate his provocative language. The cynicism of his imagery and the conviction with which he used it took my breath away. Aware that reporters were positioned three-deep along the courtroom walls, I fought hard to not allow my face to betray any emotion. Thumping the podium, he proclaimed it ironic that he, of all people, should be called an antisemite, when his publishers, editors, and lawyers had been Jews.4

Irving promised that he would prove that the “gas chambers shown to the tourists in Auschwitz is [sic] a fake built by the Poles after the war” and he would use our own experts to do so. In language more reminiscent of a Hollywood B-movie than a British court, he announced, “Perhaps the admission will have to be bludgeoned out of them.” Irving predicted that we would be completely unable to prove that he willfully manipulated, mistranslated, or distorted the evidence.5

He illustrated his contention that, rather than deny the Holocaust, he had actually brought it to the attention of others, by describing how he had publicized a document containing German general Walter Bruns’s description of the mass shooting of Jews during the summer of 1941 in Riga. After the war, Bruns was captured by the British. They secretly taped him telling his fellow POWs how the SS enthusiastically did their job. He told them how, when a Jewish woman, who had been forced to strip to her underwear, walked by on her way to be shot, an SS man commented: “Here comes a Jewish beauty!”6

Lightly beating his heart, Irving asked how could it be that he, who had publicized this document, with its detailed descriptions of killings, could be branded a “Holocaust denier”? Irving had, it was true, publicized this document. However, what he did not say was that, when he did so, he had argued that it proved that Hitler had tried to stop the shootings and that the shootings themselves were rogue unauthorized actions and not part of a program coordinated by Berlin.

Irving then plunged into a detailed dissertation on a relatively minor aspect of the trial, my claim that he had illegally taken glass plates of the Goebbels’s diaries out of the Soviet archives in Moscow. The torpid nature of this discourse, which seemed interminable, made it hard for me to keep my eyes open. Finally, Irving concluded his over two-hour discourse by returning to the conspiracy against him. “It was not just one single action that has destroyed my career, but a cumulative, self-perpetuating, rolling onslaught from every side engineered by the same people who have propagated the book which is at the centre of the dispute, . . . which is the subject of this action.” With that he sat down. He was smiling and seemed pleased with his performance.

Before Rampton began his speech, Judge Gray clarified some of the historiographic issues at the heart of the trial. Irving was arguing that we should be obligated to prove that he actually knew a specific event happened and that he then manipulated the facts. Whereas, we believed that the question was not simply whether Irving knew of a particular fact, but that the fact was readily available in the historical records and he “shut his eyes to it.”7

“HE IS A LIAR”

With a nod of his head, Judge Gray indicated that it was time for Rampton to begin. When it came to opening and closing statements, Rampton believed in economy of scale. He rose, arranged his papers, gave his wig a small tug—as if to anchor it on his head—and took a deep breath. He then looked up at Judge Gray and began with our bottom line: “My Lord, Mr Irving calls himself an historian. The truth is, however, that he is not an historian at all but a falsifier of history. To put it bluntly, he is a liar.” This case, he continued, was not about competing versions of history, but about truth and lies.

Even before becoming a denier, Rampton continued, Irving had distorted the historical record in an effort to exculpate Hitler. Hitler’s War, published a decade before Irving began to espouse denial, was riddled with examples of the “disreputable methods” Irving used to exonerate Hitler from responsibility for atrocities against Jews or any other victims.8 In the introduction, Irving promised his readers that the book contained “incontrovertible evidence” that as early as November 30, 1941, Hitler had explicitly ordered that there was to be “‘no liquidation’ of the Jews.”

Himmler was summoned to the Wolf’s Lair for a secret conference with Hitler, at which the fate of Berlin’s Jews was clearly raised. At 1:30 p.m. Himmler was obliged to telephone from Hitler’s bunker to Heydrich the explicit order that Jews were not to be liquidated. [Emphasis added]

Irving based this claim that Hitler had demanded Himmler come to a secret meeting at which he ordered that Jews were not to be murdered on Himmler’s phone log for the day. It listed a 1:30 P.M. phone call from Himmler to his assistant Reinhard Heydrich, who was in Prague. Himmler made the following notations in his log about the call:

Judentransport aus Berlin. [Jew-transport from Berlin.]

Keine Liquidierung. [No liquidation.]

The...