eBook - ePub

The Afghan Wars: History in an Hour

Rupert Colley

This is a test

Compartir libro

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

The Afghan Wars: History in an Hour

Rupert Colley

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Love history? Know your stuff with History in an Hour.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es The Afghan Wars: History in an Hour un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a The Afghan Wars: History in an Hour de Rupert Colley en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Storia y Storia mediorientale. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

StoriaCategoría

Storia mediorientaleAppendix 1: Key Players

The First Anglo-Afghan War

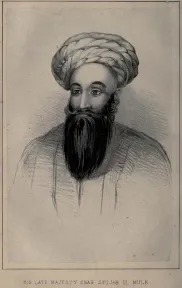

Dost Mohammad Khan 1793–1863

Dost Mohammad had ruled as Amir of Afghanistan from 1826 when, in 1839, he became embroiled in the ‘Great Game’, the intrigue between Russian and British interests in Central Asia. The British considered him unreliable and suspected that his loyalty lay with Russia. The removal of Dost Mohammad lay behind the First Anglo-Afghan War of 1839 to 1842. British forces invaded and placed their nominee, Shuja Shah, on the Afghan throne. Dost Mohammad fled and later surrendered, spending the rest of the war in captivity in British India.

Dost Mohammad

Following Britain’s withdrawal in September 1842 and the murder of Shuja Shah, Dost Mohammad returned to the throne and ruled until his death in 1863.

Shuja Shah Durrani 1785–1842

Originally the governor of Herat, Shuja Shah became Afghanistan’s king in 1803, following the deposition of his brother, until he was deposed himself six years later. He spent his years of exile in India as a guest of the British government until 1839 when Britain decided to remove the new king, Dost Mohammad, and restore the more compliant Shuja Shah to the throne.

Shah Shuja

Although successful, following Britain’s forced retreat from Kabul, Shuja Shah’s position and life were vulnerable, and on 5 April 1842 he was murdered.

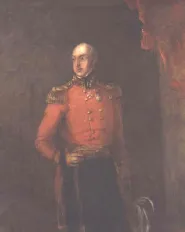

William Elphinstone 1782–1842

William Elphinstone served with distinction during Waterloo. In 1839, having had a quiet career in the British army, the 57-year-old Elphinstone was content to take command of a Bengal division in British India and eke out his final years until retirement. When, the following year, Lord Auckland, Governor-General of India, ordered him to take command of the British garrison in Kabul, Elphinstone argued his unsuitability, citing his advancing years and encroaching gout as sufficient reason. Auckland insisted and Elphinstone found himself in Kabul. But the old commander discovered that the situation was reassuringly stable with the garrison enjoying life within the walls of its cantonment.

William Elphinstone

The peace was not to last. Following the Afghan insurrection and the murder of the British resident, Alexander Burnes, Elphinstone panicked and proved incapable of making a decision. A swift retaliation should have been ordered but instead Elphinstone held numerous meetings, taking sides with whoever spoke last and deciding nothing.

With supplies dwindling and the opportunity for a show of strength lost, Elphinstone eventually negotiated with Akbar Khan from a position of weakness and Akbar’s resultant guarantee of a safe passage out of Kabul proved meaningless.

Elphinstone started out on the retreat but was taken back to Kabul as a hostage. Four months later, he succumbed to dysentery and died in captivity a broken man.

The Second Anglo-Afghan War

Sher Ali Khan 1825–79

The third son of Dost Mohammad Khan, Sher Ali became Amir of Afghanistan on his father’s death in 1863 but two years later was removed from power by his older brother, Mohammad Afzal Khan. Later, following his brother’s death in 1867, Sher Ali returned to the throne.

Sher Ali Khan

In 1878 Sher Ali became the latest pawn in the ‘Great Game’ between Russia and Great Britain. His attempts to stand up to the British were swept aside as British forces invaded his country, thereby starting the Second Anglo-Afghan War. As the British bore down on Kabul, Sher Ali fled, hoping to seek asylum in Russia, but died en route in February 1879.

Yakub Khan 1849–1923

The son of Sher Ali, Yakub Khan succeeded his father in 1879 and immediately entered into negotiations with the invading British army. He agreed to sign the Treaty of Gandamak which, in return for British subsidies, gave Britain control of Afghanistan’s foreign affairs and allowed for the presence of a British envoy, Pierre Louis Cavagnari, within Kabul.

Yakub Khan

Following Cavagnari’s murder in September 1879, Yakub Khan met with the approaching British army to plead his innocence and request leniency. Sir Frederick Roberts, in command of the British, found Yakub Khan’s presence embarrassing and, ignoring the Amir’s pleas, pushed on to Kabul.

Yakub Khan abdicated, took refuge in the British cantonment before leaving Afghanistan altogether for a life of exile in British-controlled India.

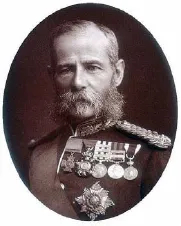

Frederick Sleigh Roberts 1832–1914

Joining the army of the British East India Company aged nineteen in 1851, Roberts first saw action during the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and was involved in the capture of Delhi. The following year he was awarded the Victoria Cross for his ‘marked gallantry’.

Frederick Sleigh Roberts

In 1879, now a major-general in the British army proper, Roberts led the occupation of Kabul during the Second Anglo-Afghan War. Then, in 1880, to relieve the British garrison besieged in the city of Kandahar, Roberts led the Kabul to Kandahar March, an event that caught the public imagination and earned Roberts the thanks of parliament and lifelong fame.

After his stint in Afghanistan, Roberts was appointed commander-in-chief, firstly in India then Ireland, during which time he was promoted to field marshal.

During the Second Boer War (1899–1902) Roberts was again appointed commander-in-chief, this time in South Africa. Forces under his command relieved the city of Kimberley ending a 124-day siege. During the Boer War Roberts’ son, also named Frederick and also a holder of the Victoria Cross, was killed in action. Roberts and his son are one of only three father/son recipients of the VC.

Roberts was in St Omer in northern France in November 1914, inspecting Indian troops soon after the outbreak of the First World War, when he caught pneumonia and died. He was eighty-two.

He was laid in state in Westminster Hall, the first of only two non-Royals to be so honoured during the twentieth century (the other, fifty years later, was Sir Winston Churchill).

Democratic Afghanistan and Soviet Era

Mohammad Daoud Khan 1909–78

Mohammad Daoud Khan served as the Afghan prime minister from 1953 to 1963 under the king, Zahir Shah, his cousin and brother-in-law. During his decade in office, and under his influence, Afghanistan drew closer to the Soviet Union, becoming dependent on Soviet imports and assistance. But tension between Afghanistan and its neighbour Pakistan forced Daoud into resigning in March 1963. The following year the king instituted a new constitution which prevented members of the royal family holding ministerial posts, thereby blocking Daoud’s plans to re-enter politics.

Mohammad Daoud Khan

Photo from Henryhartley

Photo from Henryhartley

However, in 1973, while the king was detained in Italy undergoing an eye operation, Daoud staged a coup. But rather than naming himself the king’s successor, he declared Afghanistan a republic with himself as its first president.

Daoud distanced his country from Soviet influence, thus alienating the Afghan communist party, the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (the PDPA), and alarming the Kremlin, who feared Daoud was aligning himself to the West.

The murder of a PDPA leader on 17 April 1978 convinced the Afghan communists that they were all at risk. Daoud, fearing a coup, had the leading communists arrested but nonetheless failed to prevent the revolt which, under the command of Nur Mohammad Taraki, took place on 28 April and came to be known as the Saur Revolution (Saur being Persian for April). Daoud, along with members of his family, was shot in the presidential palace.

Daoud’s death was not publicly announced and Taraki, as the new president, declared that former president Daoud had ‘resigned for health reasons’.

Daoud’s body was found thirty years later, in 2008, and in March 2009 the former president was reburied with full state honours.

Nur Mohammad Taraki 1917–79

During the mid-1960s Nur Mohammad Taraki became one of the founding members of the Afghan communist party (the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan). When, in April 1978, Mohammad Daoud, the then president, was assassinated, Taraki assumed the title of president and renamed the country the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan.

Nur Mohammad Taraki

Taraki tried to implement a series of Marxist reforms which included the emancipation of women and various land reforms, all of which were met with violent unrest. Taraki’s repressive response exacerbated an already volatile situation.

To add to Taraki’s unease, he fell out with his prime minister, Hafizullah Amin, suspecting Amin of wanting to overthrow him.

In March 1979 Taraki visited Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev, and asked for assistance. Brezhnev refused to be drawn in but offered Taraki his advice – namely to slow down the pace of reform and to remove Amin.

Taraki returned to Kabul and in September 1979 called Amin to a meeting. Amin came prepared and in the ensuing gunfight Taraki was arrested and placed in a cell, where, at some point later, he was held down and suffocated.

Amin declared himself president, announcing that Taraki had died suddenly from a serious illness.

Brezhnev, on hearing the news of Taraki’s death, wept.

Hafizullah Amin 1929–79

A former teacher, Hafizullah Amin joined the PDPA, the Afghan communist party, during the mid-1960s and was instrumental in the overthrow of Mohammad Daoud Khan in April 1978. The new communist government, headed by Nur Mohammad Taraki, isolated much of the Afghan population by its Marxist reforms. Amin expanded his powerbase to the point that Taraki was forced into naming him his prime minister. In September 1979 Amin, aware of Taraki’s plans to eliminate him, forced Taraki’s removal and later had him murdered.

Hafizullah Amin

Amin, as a means of cementing his power as the new president, purged the PDPA of his internal enemies and terrorized the Afghan population. Deeply unpopular at home, Amin was also distrusted in Moscow and disl...