![]()

Chapter 1

“Commutative Goodnesse”: Food

and Leadership

One of the earliest and most weighty decisions facing the backers of England’s early colonies was choosing a leader, and most writers on the subject were in agreement on the fundamentals. Richard Eburne, for example, wrote that “Governours and Leaders of the rest” should be chosen from “men of Name and Note.” In other words, leaders were expected to be men whose “power and authoritie, greatnesse and gravitie, purse and presence” supported their claim to lead. The circularity of Eburne’s reasoning—that “authoritie” and “greatnesse” qualified a man for positions that conferred precisely these qualities—derived from assumptions widely shared by the early modern English. Since all hierarchy had its roots in “the very order of Nature,” as Eburne put it, one of these assumptions was that the powers of office and the qualities that legitimated a claim to hold it were mutually supporting.1

Another basic assumption was that the legitimacy of a leader could be seen in his ability “to order and rule, to support and settle the rest.” William Strachey, a Virginia Company official who traveled to the Chesapeake in 1609, echoed these remarks when he described “order and governement” as “the onely hendges [hinges], whereupon, not onely the safety, but the being of all states doe turne and depend.” Without them, he asked, “what society may possibl[y] subsist, or commutative goodnesse be practised”? To the early modern English, social order was the result of proper “governement,” in Strachey’s terms. The right sort of leader produced a harmonious society built on reciprocal ties binding the commons and their leaders to the benefit of all.2

These assumptions underlay all discussions and descriptions of leadership in the early period, and food was central to any image of an effective leader, whether Native American or English. Arthur Barlowe’s descriptions of Granganimeo’s authority over the Carolina Sounds, to take one example, were dominated by the varied and abundant foods he alone was able to provide the English travelers. Just as abundance was a sign of proper government, dearth encapsulated the opposite.

Nearly all of the familiar features of English society were absent in the early Atlantic world, and as a result disagreements soon emerged among English travelers, settlers, and metropolitan officials. The scholarly literature often infers a lack of coherence, not to mention competence, from these disagreements and the violence, hunger, disease, and death that marked nearly every settlement’s first years. And yet given the substantial investment required, every feature of the early English settlements was carefully planned, then monitored and adjusted to maximize the chances of success. The choice of a leader was of paramount importance to a settlement’s stability and profit, and the question received careful attention. But since no one could claim a record of success in building a profitable English settlement in the early period, there were no clear models to follow.

In their search for effective leaders, all those concerned recognized that some improvisation would be necessary. The leaders appointed to govern England’s first efforts at settlement were not surprised to find themselves without the familiar props with which to stage a demonstration of their authority, but they were not entirely without guidance or precedent. They drew on others’ experience and volumes of manuscript and printed sources to derive lessons that they thought would ensure peace, health, stability, and profit. The first English settlements in the New World represented the fruition of earlier efforts as much as the start of an English presence in the Americas, and English leaders set sail knowing they would have to observe carefully, adjust their expectations when necessary, and above all learn from their mistakes. Despite their differences, the backers and officials of all early projects shared the same assumptions about leaders’ authority and the same goal of peaceful, orderly, and prosperous settlements. Just as it was for Thomas Tusser and Arthur Barlowe, abundant food was the most potent sign of these larger meanings.

The popularity of Tusser’s Five hundreth points of good husbandry signals the extent of agreement on the normative model of English society that he sketched. The sort of rural household Tusser described, a social microcosm whose prosperity and order were encapsulated in the varied and abundant foods it produced, would take generations to establish in the Americas, not months or years. So would the horizontal and vertical social ties that interlinked such households on occasions like Christmas feasts. Rural elites, who in England played a vital role in mediating disputes and administering justice, were almost wholly absent in the early settlements, as were churches, whose hierarchy paralleled and supported secular inequalities. Even women, whose labor was essential to Tusser’s idealized household, were rare. Since the hierarchies that structured English society were so tightly interwoven, the absence of churches, landlords, and (especially) families had sweeping effects.

Tusser among many others viewed the household, ruled by father, husband, and master, as the foundation of English society. A man’s authority over his family was reproduced on a larger scale by the leaders of English villages, parishes, towns, and counties and culminated in the monarch’s authority over the kingdom as a whole. All social inequalities, all reciprocal bonds between inferiors and superiors, stemmed from the same divine ordering. Richard Brathwaite summed up with a familiar metaphor: “As every mans house is his Castle, so is his family a private Common-wealth, wherein if due government be not observed, nothing but confusion is to be expected.” The magistrates of the Massachusetts Bay settlement similarly proclaimed that “A family is a little common wealth, and a common wealth is a greate family.”3

The contemporary understanding of the connection between these very different relationships was not metaphorical. A father was the king of his family and a king the father of his subjects: the source of these two claims to authority was the same divine “order of Nature” that Eburne described. Accordingly, household government was linked directly in English law to the formal levels of government. Nathaniel Butler, governor of Bermuda, defined petty treason as the murder “by an inferior” of his or her “superior,” one who “hath a dominion, and a kind of majestie and regalitie as it wer, in ruleinge over the sayd partie.” The examples Butler gave were a child murdering a parent, a servant his master or mistress, or a wife her husband. Petty treason represented an attack on the same structure of hierarchy and authority that supported and legitimated the monarch: a threat to any one of these hierarchical relationships was a threat to the whole edifice that supported monarchical power.4

English writers often described social relationships by reference to the human body, pointing out that the health and success of the entire organism depended on direction by a head but also on the strength and cooperation of its various parts. Gardening and horsemanship were other metaphors for authority, examples in which order and beauty were produced by the skill, knowledge, and control of a single person. Each expressed the same vision of society and authority. Whether the lower orders of society were akin to horses, flowers, or feet, they could not be orderly or productive without the direction of the higher orders, the “commutative goodnesse” William Strachey described as characterized by “order and governement.” As Kevin Sharpe has pointed out, it “might take a considerable imaginative leap for us to comprehend that bee-keeping might be or become an ideological act,” but government of bees and of a kingdom expressed the same fundamental truths.5

One of these was that inequality was part of the natural order and necessary for a stable, harmonious, and prosperous society. The result of a leader’s effective exercise of authority was not submission or obedience for its own sake but the mutual benefit of rulers and those subject to them. One of the most tangible symbols of this unequal yet harmonious interdependence was food, produced by the labor of the lower orders but abundant owing to the government of those at the top.

These idealized descriptions provided elites with a comforting set of assumptions: that the social hierarchy was rooted in a divine plan and therefore was immutable in its basic contours and that their place at its higher reaches was secure. But in practice, the social relationships of early modern England were neither as static nor as consensual as these descriptions suggest. Elites often found that their claims to precedence and their ability to exercise the powers of political office—in other words, their authority—required the consent of ordinary people, and this was never more true than during periods of widespread hunger.

One of the distinctive features of early modern English politics was the fact that the monarch and Privy Council depended on lesser officials in the localities to interpret and implement royal policies. Local elites might serve as “deputy lieutenants, JPs, town magistrates, sheriffs and grand jurors,” while their “middling and even more humble” neighbors could expect to serve as “constables, beadles, tithingmen, nightwatchmen, vestrymen, overseers of the poor, trial or petty jurors, or even perform a stint in the militia or trained bands.”6

Although the authority of a leading official like a justice of the peace or lord lieutenant was granted by the monarch, the social standing that qualified a man to hold such an office had its roots in the local community. In part, this explains the circularity of Richard Eburne’s reasoning that officials should be chosen from among those who already have “greatnesse” and “authoritie.” These characteristics of office also meant that a man’s authority was rooted in local ties as much as connections to powerful superiors. By mediating the desires of those above him in the hierarchy with local assumptions about the proper role of those in authority, an officeholder solidified his claim to local status and effective leadership. In this way, local elites might be named to more powerful offices, which opened up new patronage opportunities, augmented local standing, and improved chances for further honors.7

Just as Tusser’s Christmas feast signaled a prosperous and properly ordered household, abundance of food was a sign of a properly ordered commonwealth. Dearth was among the most powerful signs of the opposite, a challenge local officeholders struggled to explain and address in the late Tudor period. The nature of the problem was complex. A rapid rise in England’s population in the second half of the sixteenth century occurred as elites engrossed larger landholdings and enclosed common lands. As a result, England’s larger, younger population had a much harder time finding access to land and livelihoods than had previous generations, which contributed to unprecedented geographic mobility. Alongside these economic and demographic trends, the “Little Ice Age” contributed to lower crop yields and shorter growing seasons. When harvests failed in 1586, 1594–98, 1623–24, and 1630, the situation seemed to many to have reached crisis proportions.8

To contemporary elites, the nature of these social and economic changes was opaque, and their response was based on fear of instability, on a perceived rent in the social fabric symbolized by the increasing visibility and mobility of the poor. The response at the highest levels of government was to treat vagrancy as a “status crime.” Even absent any criminal actions committed by vagrants themselves, vagrancy violated elites’ normative social vision, which expected that every able-bodied young man would be rooted to a community, a family, a parish, a landlord, a master. The “masterless men” roaming the countryside posed a threat to the social order because they were not subject to “government” in the all-embracing early modern sense of the term.9

The response of the Privy Council and the monarch was premised on the assumption that vagrancy was an individual failing worthy of punishment. The idle poor, meaning the able-bodied, were to be punished as criminals and the deserving poor supported by their local community. Crucially, this distinction between idle and deserving poor was made at the local level, by local officeholders based on local considerations of how much relief was available and whether or not those seeking it could make a claim on the resources of their neighbors. The role of local officeholders in this process was to respond to perceived threats to social order and stability in a way that resonated with the widely shared assumptions of reciprocal obligation, to reconcile elite demands for order with the commons’ demands for relief.10

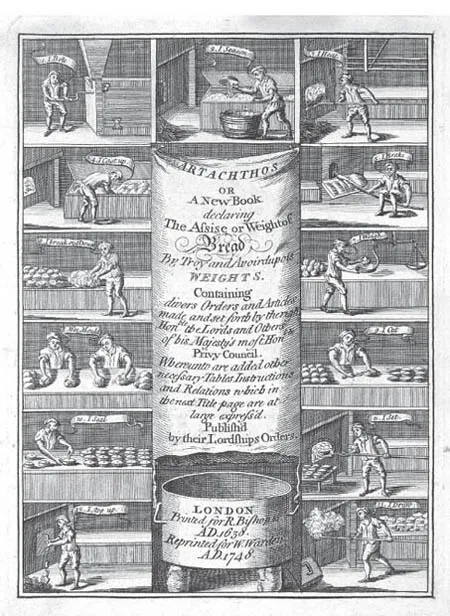

Figure 7. Surrounding the title of John Penkethman’s Artachthos (London, 1638; repr. 1748) are a series of illustrations depicting the various stages in baking bread, from bolting the flour (top left) to drawing the baked loaves from the oven (bottom right). Penkethman’s text described the Assize of Bread, the English law that specified the permissible weight for a loaf of a given price. Courtesy Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

The purest expression of these assumptions was the dearth orders, issued by the monarch to guarantee the availability of grain during times of scarcity. In the medieval period, when landlords often collected rents in grain and other foods, elites were expected to distribute the stored food under their control to those subject to their authority, an enactment of the reciprocal obligations thought to underpin society as a whole. In the early modern period, rents were more likely paid in cash, but elites’ role in guaranteeing the availability of food in the monarch’s name remained. In place of grain stores under manorial control, local elites oversaw the operation of grain markets within their jurisdiction. According to the dearth orders, grain was only to be transported on market day, to ensure that private sales did not circumvent the public market. Before the market opened, local officeholders met with sellers to establish a price for the grain. Those who needed grain to feed their households were given the first opportunity to purchase small quantities as soon as the market opened, and commercial buyers could enter the market only afterward to buy larger amounts.11

As was true of any statute, the effectiveness of the dearth orders depended on the efforts of local officeholders. But it was especially important in this case that those efforts be undertaken in public, in full view of what Frank Whigham has called the “enfranchising audience” of the local community. By exercising the powers of their office in public, local elites demonstrated that the commons’ assumptions of reciprocity held true, that leaders cared for ordinary people and would act in times of need to ensure their well-being. Officeholders’ conduct on these occasions was closely watched. The expectations of the commons had to be considered in a leader’s performance of his duties, since ordinary people were hardly passive observers, especially during times of dearth. Officials understood that just as a successful performance of office might augment social standing, the reverse was also true.12

When harvests failed, urban areas that relied on grain markets and distant suppliers were most severely ...