![]()

1 Matrix matters

An overview

The birds of New York and the coffee of Mesoamerica

Bird-watching requires a morning buzz. The best sightings occur with the rising sun, and even the most enthusiastic bird-watcher normally has to have an all-important cup of Joe before setting out to increment that ever-expanding list of species ‘gotten’ (the word bird-watchers normally use for ‘having seen’). But the association of birds with coffee turns out to be far more important than the casual need for stimulants to get going in the morning.

It all started when someone noticed a striking coincidence: populations of songbirds in the eastern US were declining at the same time as some Latin American countries were engaged in the ‘technification’ of their coffee production systems in the never-ending quest for higher production. Technification1 meant elimination of the shade trees that normally covered the coffee bushes in the more traditional form of growing coffee. Those traditional coffee farms were known to be forest-like habitats for various kinds of birds (Figures 1.1 and 1.2). Many of the songbirds that experienced population declines were migratory species that flew south for the winter. Putting a couple of evident observations together, it was not a gigantic leap in logic to suggest that eliminating the shade trees that constituted most of their wintering habitat would have a significant impact on those birds that sought the tropical climates to avoid the northern winter.

It remains debatable as to how much of the decline in populations of North American songbirds can be directly attributed to the technification (or intensification) of coffee production in Latin America. Regardless, the logic of the situation was enough to mobilize many people – bird-watchers, conservationists, environmentalists – to become apprehensive about this transformation of an agroecosystem. And that apprehension was a watershed. Previously, there had always been a kind of knee-jerk attitude that agriculture automatically meant degradation of natural habitat, which obviously translated into a loss of biodiversity, bird and otherwise. But here we have a case where it was arguably the type of agriculture – not the simple existence of agriculture, rather its particular form – that was having an effect on biodiversity.

Figure 1.1 Songbirds that are commonly found in coffee plantations in the Neotropics.

Source: Gerhard Hofmann.

Figure 1.2 A shaded coffee plantation that serves as habitat for Neotropical migratory birds.

Source: Hsun-Yi Hsieh.

What emerged from the coffee–biodiversity connection was a new discourse about nature. Previously, conservationists had clearly separated agricultural systems from natural ones in terms of their value for biodiversity conservation. But the discovery that many birds apparently could not tell the difference between a diverse canopy of shade trees in a traditional coffee plantation and a diverse canopy of trees in a natural forest caused a reassessment of the very idea of ‘natural’. Was it legitimate to be concerned with keeping the remaining small tracts of untrammelled tropical forest forever untrammelled? If we just ignored the coffee technification were we not insisting that the birds adopt our particular interpretation of what a natural forest was? If the birds were mainly concerned with the existence of shade canopy cover and not so much with where it came from or who managed it (nature or a farmer), should we maybe rethink our peculiar notion of natural as something managed only by ‘nature’ and never by a farmer?

The debate still rages. Indeed, this book is in part intended to inform one piece of that debate. On the one hand, it is tacitly assumed that the proper goal is to intensify agriculture so as to produce as much as possible on as little land as possible, thus leaving the maximum possible amount of land under ‘natural’ conditions. On the other hand – and this is our position – agroecosystems are important components of the natural world, intricate to biodiversity conservation. Consequently, their thoughtful management should be part of both a rational production system and a worldwide plan for biodiversity conservation. To fully explain our position requires focusing on three areas:

1 the nature of biodiversity itself;

2 how we have arrived at our current state of agroecosystem management; and

3 the current way that humans relate to tropical landscapes.

These three areas are the topics of Chapters 2–7. In Chapters 8–10 we present some examples of how these three areas intersect in the real world. We conclude, in Chapter 11, with our full argument of what we regard as a new practical programme that derives from the underlying social and biological theory.

In the present chapter we provide an overview of the three areas, followed by a glimpse at what we regard as a new paradigm of conservation.

The argument

The ecological argument

In the last few years we have flown over areas that used to be continuous tropical forest in eastern Nicaragua, southern Brazil, southern Mexico, south-western India, and south-western China. In a general way, all areas look very similar: a patchwork of forest fragments in a matrix of agriculture (Figure 1.3). With few exceptions (mainly in the Amazon and Congo basins), the terrestrial surface of the tropics looks like this. And we always remain mindful that this is the location of the overwhelming majority of the world’s biodiversity. So, if we are concerned in general with biodiversity conservation in the world, we ought to be concerned with what is happening in the tropics.

If most of the tropical world is a patchwork of fragments in a matrix of agriculture, and most of the world’s biodiversity is located in tropical areas, should we not be concerned with understanding the reality of that patchwork? Yet the vast majority of conservation work concentrates on the fragments of natural vegetation that remain, and ignores the matrix in which they exist. Even at the most superficial level, it would seem that ignoring a key component of what is obviously a highly interconnected system is unwise.

The bias that favours concentrating efforts on the fragments while ignoring the matrix is far more damaging to conservation efforts than first meets the eye. As we argue in detail in Chapter 2, the matrix matters. It matters in a variety of social and political ways, but more importantly, it matters in a strictly biological/ecological sense. Recent research in ecology has made it impossible to ignore this fact. The fundamental idea has to do with the notion of a metapopulation.2 Many, perhaps most, natural biological populations do not exist as randomly located individuals in a landscape. Rather, there are smaller clusters of individuals that may occur on islands, or habitat islands, or simply form their own clusters by various means. These clusters are ‘subpopulations’, and the collection of all the clusters is a ‘metapopulation’. The critical feature of this structure is that each subpopulation faces a certain likelihood of extinction. Accumulated evidence is overwhelming that extinctions, at this local subpopulation level, are ubiquitous. What stops the metapopulation from going extinct is the movement of individuals from one cluster to another. So, for example, a subpopulation living on a small island may disappear in a given year, but if everything is working right, that island will be repopulated from individuals migrating from other islands at some time in the near future. There is thus a balance between local extinction and regional migration that protects the metapopulation from going extinct at the regional level.

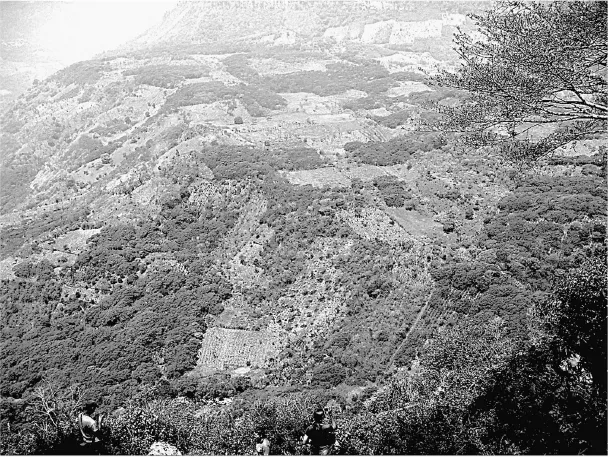

Figure 1.3 A fragmented landscape in Chiapas, Mexico.

Source: John Vandermeer.

Note

Fragments of natural vegetation are embedded in an agricultural matrix.

There is now little doubt that isolating fragments of natural vegetation in a landscape of low-quality matrix, like a pesticide-drenched banana plantation, is a recipe for disaster from the point of view of preserving biodiversity. It is effectively reducing the migratory potential that is needed if the metapopulations of concern are to be conserved in the long run. Whatever arguments exist in favour of constructing a high-quality matrix, and there are many, the quality of the matrix is perhaps the critical issue from the point of view of biodiversity conservation. The concept of ‘the quality of the matrix’ obviously must be related to the natural habitat that is being conserved, but most importantly, it involves, at its core, the management of agricultural ecosystems.

The agroecological argument

When considering agriculture, the research establishment has become mesmerized by a single question: How can we maximize production? Rarely is it acknowledged that such a goal is really quite new, probably with a history of less than a couple of hundred years, and little more than 60 years old in its most modern form. In recent years there have been major challenges to this conventional agricultural system, all of which, in one form or another, involve questioning this basic assumption. Why should maximization of production be a goal at all? We return to this question in Chapter 4. But for now, suffice it to say that many analysts have concluded that environmental sustainability, social cohesion, cultural survival, and other similar goals are at least equally as important as maximizing production, creating two attitudinal poles in what has become as much an ideological struggle as a scientific debate.3

This fundamental contradiction in attitudes is reflected most strongly in the alternative agricultural movement, especially among those who study agriculture from an ecological perspective. There is a distinct feature of more ecologically based agriculture that must be recognized here. Ecological scientists, in general, tend to have a certain mind-set, largely derived from the complexity of their subject matter. This mind-set is most easily appreciated by comparing the mind-set of a typical agronomist with a typical ecologist, especially an agroecologist. Both seek to understand the ecosystem they are concerned with, the farm or the agroecosystem. And both have the improvement of farmers’ lives as a general practical goal. But the ways they approach that goal tend to be quite different.

Consider, for example, the classic work of Helda Morales.4 In seeking to understand and study traditional methods of pest control among the highland Maya of Guatemala, she began by asking the question, ‘What are your pest problems?’ Surprisingly, she found almost unanimity in the attitude of the Mayan farmers she interviewed – ‘We have no pest problems.’ Taken aback, she reformulated her question, and asked, ‘What kind of insects do you have?’, to which she received a large number of answers, including all the main characteristic insect pests of maize and beans in the region. She then asked the farmers why these insects were not a problem for them, and again received all sorts of answers, always connected to how the agroecosystem was managed. The farmers were certainly aware that these insects could be problematic, but they also had ways of managing the agroecosystem so that the insects remained below levels that would categorize them as pests. Morales’ initial approach was probably influenced by her original training in agronomy and classical entomology, but her interactions with the Mayan farmers caused her to change that approach. Rather than study how Mayan farmers solve their pest problems, she focused on why the Mayan farmers do not have pest problems, in the first place.

Here we see a characterization of what might be called the two cultures of agricultural science: that of the agronomist (and other classical agricultural disciplines such as horticulture, entomology, etc.) and that of the ecologist (or agroecologist). The agronomist asks, ‘What are the problems the farmer faces and how can I help solve them?’ The agroecologist asks, ‘How can we manage the agroecosystem to prevent problems from arising in the first place?’ This is not a subtle difference in perspective but rather a fundamental difference in philosophy. The admirable goal of helping farmers out of their problems certainly cannot be faulted on either philosophical or practical grounds. Yet with this focus we only see the sick farm, the farm with problems, and never fully appreciate the farm running well, in ‘balance’ with the various ecological factors and forces that, in the end, cannot be avoided. It is a difference reflected in other similar human endeavours – preventive medicine versus curative medicine, regular automotive upkeep versus emergency repair, etc. The ecological focus of asking how the farm works is akin to the physiologist’s focus of asking how the body works. The agronomist only interv...