eBook - ePub

Food Aid After Fifty Years

Recasting its Role

Christopher B. Barrett, Dan Maxwell

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Food Aid After Fifty Years

Recasting its Role

Christopher B. Barrett, Dan Maxwell

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

This book analyzes the impact food aid programmes have had over the past fifty years, assessing the current situation as well as future prospects. Issues such as political expediency, the impact of international trade and exchange rates are put under the microscope to provide the reader with a greater understanding of this important subject matter.This book will prove vital to students of development economics and development studies and those working in the field.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Food Aid After Fifty Years est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Food Aid After Fifty Years par Christopher B. Barrett, Dan Maxwell en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Business et Business General. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

1

The basics of food aid

As with much of the development business, food aid practitioners employ a bewildering array of opaque terms and peculiar acronyms that can make it a bit difficult for outsiders to comprehend even the broad contours, much less the details, of conceptual, policy and operational debates. This brief chapter, supplemented by the Glossary at the end of the book, aims to introduce the basic concepts, terminology, and patterns that must be understood prior to serious reflection on the role and design of an effective food aid strategy.

The misunderstanding of food aid begins with an ongoing, basic definitional issue.1 The term “food aid” is commonly, but inaccurately, used to refer to the donation of food to recipient individuals and households. By this standard, Americans would be among the world’s most numerous food aid recipients because of the extent of the school feeding in the United States, temporary assistance to needy families, food stamps, and other “food assistance programs.”2 Indeed, even private donations for neighborhood feeding programs – including such common activities as parental programs to provide mid-morning snacks to school children3 – would qualify as “food aid” under such a broad definition, underscoring how such an expansive definition quickly loses its usefulness. The defining feature of food aid relates neither to the identity of final recipients, who may or may not need additional food beyond that they can produce or procure on their own, nor to the form of transfer. As we will discuss, much food aid gets turned into cash by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) or private voluntary organizations (PVOs) and governments and therefore is not distributed as food to hungry people, while “food aid” can likewise take the form of cash donations used to purchase foods in surplus regions of the recipient country for distribution elsewhere. Rather, three core characteristics distinguish food aid from other forms of assistance:

(1) the international sourcing

(2) of concessional resources

(3) in the form of or for the provision of food.

Without some cross-border flow of food or cash for the purchase of food and without there being a significant grant element, the flow is simply not food aid. Food aid is thus as much an issue of procurement as one of distribution, and it is most fundamentally an entry into nations’ balance of payments. Food transfers that do not have corresponding balance of payments entries – such as school feeding programs in the United States, European prenatal nutrition programs, and food subsidies in much of the world – are not internationally sourced, they do not involve donations from another country. Such programs are not food aid even though they involve assistance related to food. Similarly, commercial international trade in food fails to meet the concessional element of the definition because there is no donation involved. Finally, international flows of financial aid that are unrelated to food (e.g., for military equipment or technical assistance) obviously do not qualify as food aid.

Modest flows intended to make a big difference at the margin

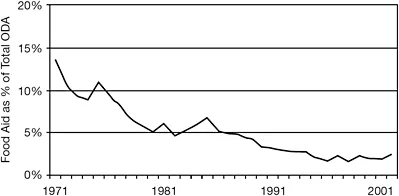

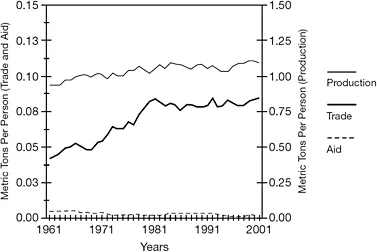

Food aid’s visibility during crises masks a meagerness that many observers do not fully appreciate. While food aid was once a central part of overseas development assistance (ODA) provided by wealthier countries to poorer ones,4 since 1995 it has averaged less than 2 percent of ODA (Figure 1.1). Not only is food aid a small portion of total foreign aid flows, it pales in comparison to domestic production and commercial trade flows as a source of food. Figure 1.2 underscores how food production and commercial food trade dwarf food aid flows today.5 (Notice that production is measured against the right-hand axis, which is ten times larger than the left-hand axis against which aid and trade flows are measured!) While commercial food trade flows have grown steadily over time, accelerating especially sharply in the 1960s and 1970s, with slower growth in food trade thereafter, food aid flows have fallen by about two-thirds, averaging only 2 percent of food trade flows, from 1995–2000, and 0.15 percent of food production volumes over that period.6 Even food aid flows to the poorest countries have halved in per capita terms since 1992.7

Globally, the volume of food aid is too limited to supplant production or trade as a source of food other than for very brief periods in very localized situations. Rather, the humanitarian objective of food aid is to make a big difference at the margin by relieving shortfalls in food availability that contribute directly to widespread, often acute hunger, malnutrition, and undernutrition, shortfalls that local markets cannot fully correct if poor people are just provided cash.8

Enough food is produced globally to meet every person’s dietary requirements adequately. In 2000, the world enjoyed a daily per capita supply of more than 2,800 kilocalories and 75 grams of protein, more than enough to keep every man, woman, and child well nourished.9 Such ample global food supplies are a relatively recent phenomenon. In 1961, the equivalent figures were only 2,256 kilocalories and 62 grams of protein daily per capita. The world has enjoyed an increase in daily average nutrient supply per person of 21–24 percent in just forty years, an historically unprecedented achievement. The technological advances in agricultural productivity that brought about such growth have resolved the global food aggregate supply problem, at least for current generations.

Figure 1.1 The decline of food aid within ODA

Source: OECD/DAC

Figure 1.2 Global annual food flows

Source: OECD/DAC

In spite of this global plenitude, the most recent estimates of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) suggest that roughly 852 million people – more than one person in eight worldwide – do not get enough to eat.10 Many more than that are at risk of having insufficient access to food to maintain good health at intermittent points in time. The aggregate global food availability figures mask tremendous discrepancies among individuals and communities around the world, both within and between countries. Inequitable distribution within countries, within communities and even within households, is distressingly high. For example, the most recent data show that one in ten households in the United States – the country with the greatest per person food supplies in the world – experiences hunger or the risk of hunger.11 Such intra-national variation is the subject of domestic policy, especially with respect to food assistance programs such as food stamps, food subsidies, school feeding programs, food price stabilization policies and the like.12 While we recognize and are concerned about discrepancies in equitable food distribution at all these levels, the broader challenge of alleviating hunger and undernutrition globally lie beyond the scope of this book.

International food policy must address sharp discrepancies between countries in food availability. An expert consultation convened by the FAO established a daily caloric intake minimum of 2,350 per person as a goal.13 Yet even in terms of average national consumption, a very rough indicator of food security, FAO food balance sheet data14 suggest that about sixty countries fall below this threshold. Roughly two-thirds of these are in Sub-Saharan Africa. While the roughly 280 million people in the United States enjoyed daily supplies per person of 3,772 calories and 114 grams of protein in 2000 – up 30 and 20 percent, respectively, from 1961 – the equivalent figures for Sub-Saharan Africa’s more than 600 million people were only 2,226 calories and 54 grams of protein – up only 6 and 3 percent, respectively, since 1961. Stagnant productivity per capita and limited hard currency earnings with which to import food generate large-scale food availability shortfalls in much of the world. Food deficiencies at national and even continental scales in a world of global surpluses underscore that the contemporary food security challenge is partly a problem of stimulating agricultural productivity in some poorer ...