![]()

Part One

Theoretical Analysis

“The most valuable of all capital is that invested in human beings.”

Alfred Marshall, Principles of Economics

![]()

CHAPTER III

Investment in Human Capital: Effects on Earnings1

The original aim of this study was to estimate the money rate of return to college and high-school education in the United States. In order to set these estimates in the proper context, a brief formulation of the theory of investment in human capital was undertaken. It soon became clear to me, however, that more than a restatement was called for; while important and pioneering work had been done on the economic return to various occupations and education classes,2 there had been few, if any, attempts to treat the process of investing in people from a general viewpoint or to work out a broad set of empirical implications. I began then to prepare a general analysis of investment in human capital.

It eventually became apparent that this general analysis would do much more than fill a gap in formal economic theory: it offers a unified explanation of a wide range of empirical phenomena which have either been given ad hoc interpretations or have baffled investigators. Among these phenomena are the following: (1) Earnings typically increase with age at a decreasing rate. Both the rate of increase and the rate of retardation tend to be positively related to the level of skill. (2) Unemployment rates tend to be inversely related to the level of skill. (3) Firms in underdeveloped countries appear to be more “paternalistic” toward employees than those in developed countries. (4) Younger persons change jobs more frequently and receive more schooling and on-the-job training than older persons do. (5) The distribution of earnings is positively skewed, especially among professional and other skilled workers. (6) Abler persons receive more education and other kinds of training than others. (7) The division of labor is limited by the extent of the market. (8) The typical investor in human capital is more impetuous and thus more likely to err than is the typical investor in tangible capital.

What a diverse and even confusing array! Yet all these, as well as many other important empirical implications, can be derived from very simple theoretical arguments. The purpose here is to set out these arguments in general form, with the emphasis placed on empirical implications, although little empirical material is presented. Systematic empirical work appears in Part Two.

In this chapter a lengthy discussion of on-the-job training is presented and then, much more briefly, discussions of investment in schooling, information, and health. On-the-job training is dealt with so elaborately not because it is more important than other kinds of investment in human capital—although its importance is often underrated—but because it clearly illustrates the effect of human capital on earnings, employment, and other economic variables. For example, the close connection between indirect and direct costs and the effect of human capital on earnings at different ages are vividly brought out. The extended discussion of on-the-job training paves the way for much briefer discussions of other kinds of investment in human beings.

1. On-the-Job Training

Theories of firm behavior, no matter how they differ in other respects, almost invariably ignore the effect of the productive process itself on worker productivity. This is not to say that no one recognizes that productivity is affected by the job itself; but the recognition has not been formalized, incorporated into economic analysis, and its implications worked out. I now intend to do just that, placing special emphasis on the broader economic implications.

Many workers increase their productivity by learning new skills and perfecting old ones while on the job. Presumably, future productivity can be improved only at a cost, for otherwise there would be an unlimited demand for training. Included in cost are the value placed on the time and effort of trainees, the “teaching” provided by others, and the equipment and materials used. These are costs in the sense that they could have been used in producing current output if they had not been used in raising future output. The amount spent and the duration of the training period depend partly on the type of training since more is spent for a longer time on, say, an intern than a machine operator.

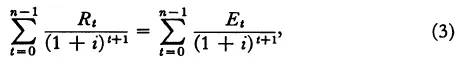

Consider explicitly now a firm that is hiring employees for a specified time period (in the limiting case this period approaches zero), and for the moment assume that both labor and product markets are perfectly competitive. If there were no on-the-job training, wage rates would be given to the firm and would be independent of its actions. A profit-maximizing firm would be in equilibrium when marginal products equaled wages, that is, when marginal receipts equaled marginal expenditures. In symbols

where W equals wages or expenditures and MP equals the marginal product or receipts. Firms would not worry too much about the relation between labor conditions in the present and future, partly because workers would only be hired for one period and partly because wages and marginal products in future periods would be independent of a firm’s current behavior. It can therefore legitimately be assumed that workers have unique marginal products (for given amounts of other inputs) and wages in each period, which are, respectively, the maximum productivity in all possible uses and the market wage rate. A more complete set of equilibrium conditions would be the set

where t refers to the tth period. The equilibrium position for each period would depend only on the flows during that period.

These conditions are altered when account is taken of on-the-job training and the connection thereby created between present and future receipts and expenditures. Training might lower current receipts and raise current expenditures, yet firms could profitably provide this training if future receipts were sufficiently raised or future expenditures sufficiently lowered. Expenditures during each period need not equal wages, receipts need not equal the maximum possible marginal productivity, and expenditures and receipts during all periods would be interrelated. The set of equilibrium conditions summarized in equation (2) would be replaced by an equality between the present values of receipts and expenditures. If Et and Rt represent expenditures and receipts during period t, and i the market discount rate, then the equilibrium condition can be written as

when n represents the number of periods, and Rt and Et depend on all other receipts and expenditures. The equilibrium condition of equation (2) has been generalized, for if marginal product equals wages in each period, the present value of the marginal product stream would have to equal the present value of the wage stream. Obviously, however, the converse need not hold.

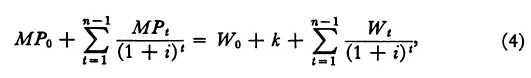

If training were given only during the initial period, expenditures during the initial period would equal wages plus the outlay on training, expenditures during other periods would equal wages alone, and receipts during all periods would equal marginal products. Equation (3) becomes

where k measures the outlay on training.

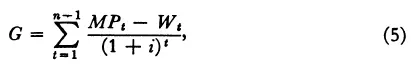

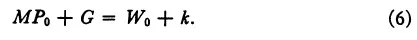

If a new term is defined,

equation (4) can be written as

Since the term k mea...