Anti-War Movement

The Anti-War Movement refers to a collective effort by individuals and groups to oppose and protest against war and military intervention. It has been a prominent feature of many historical periods, with activists advocating for peaceful resolutions to conflicts and criticizing government policies that lead to war. The movement often involves demonstrations, rallies, and other forms of public activism to raise awareness and promote peace.

5 Key excerpts on "Anti-War Movement"

- eBook - ePub

War

Contemporary Perspectives on Armed Conflicts around the World

- Cameron D. Lippard, Pavel Osinsky, Lon Strauss(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

...Although research is scant on how effective these efforts have been, there is consensus that antiwar organizations and peace activists have chipped away at pro-war cultural ideologies. They have also pushed humanity to find ways to negotiate conflict without violence by finding ways to resolve differences and bring about social justice for the disenfranchised. However, antiwar movements are different from most antiwar organizations, peace movements, and other social movements that we have grown to understand (i.e., the American Civil Rights Movement or Feminist Movement). Daniel Lieberfeld’s (2008) article on antiwar movements defines and explains how antiwar movements are different. First, he suggests that an antiwar movement is an ad-hoc movement that attempts to change government policy regarding a specific and ongoing war. Thus, this movement usually addresses a specific policy or incident and looks for a negative peace solution. However, social justice movements often want their movement to create results more closely aligned with positive peace in which grievances and reconciliation are goals. Second, antiwar movements also claim that those who control the state have broken their social contract with its citizens to bear the burden of an unnecessary and harmful war (i.e., death through military participation). While this notion that the government is not holding up its part on the contracts of civil society in other movements, antiwar movements suggest that politicians and governments are not making rational decisions about armed conflict and are not considering the human and economic costs. Thus, it is a movement against the state and its use of the military. Lieberfeld (2008) argues that this stance can seem to many as unpatriotic in a country in which nationalism is strong and requires homeland security...

- April Carter(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

...Protesters also tend to stress the brutality and immorality of the methods used by their government in waging the war: for example opponents of the Boer War in Britain pointed to the use of concentration camps. The mainspring of campaigns against specific wars has, however, been anti-imperialism. This has been combined with a simple human resistance to being drafted overseas to face death or injury, especially when victory looks uncertain and the cause dubious. Conscripts may simply rebel against the grimness of army life. All these elements were present in the protests against the French War in Algeria. During 1955 and 1956 there were widespread demonstrations and petitions, some conscripts refused to leave for Algeria and women lay down in front of troop trains. A committee set up in 1958 indicted French use of torture and repression against Algerians, and by 1960 intellectuals and students were protesting bitterly. Some potential conscripts went into hiding or escaped abroad, and they were openly supported in a public manifesto signed by 121 intellectuals. 7 War resistance can, however, be extended to active support for those justly fighting for independence. In France the highly controversial Jeanson network offered direct assistance to the Algerian National Liberation Front, and in the eyes of many discredited the wider opposition. So not all forms of resistance to specific wars can count as being part of a ‘peace movement’. Anti-imperialism is not the only reason for opposing wars as unjust. Just War doctrine and popular perceptions distinguish between genuinely defensive wars and acts of aggression. So it is not surprising that the 1982 Israeli incursion into the Lebanon to crush the Palestine Liberation Organization, which could not, like the wars of 1967 and 1973, be seen as a legitimate response to a military threat from Arab states, provoked major public demonstrations against the government...

- eBook - ePub

Kill for Peace

American Artists Against the Vietnam War

- Matthew Israel(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- University of Texas Press(Publisher)

...F. Stone’s Weekly, and the New York Review of Books. The New York Review of Books arguably offered the most sustained concentration of antiwar writings for the largest readership. 48 There were also small, although influential, mainstream publishing projects that sought to feature and promote intellectual opposition. One was Authors Take Sides on Vietnam: Two Questions on the War in Vietnam Answered by the Authors of Several Nations, published by Simon and Schuster in 1967. Its construction was relatively simple, though it contained a wealth of intellectual perspectives. Its editors, John Bagguley and Cecil Woolf, invited more than three hundred well-known authors from several countries to answer the following questions: “Are you for, or against, the intervention of the United States in Vietnam? How, in your opinion, should the Vietnam conflict be resolved?” Before discussing the antiwar movement any further, it must be said that it did not function independently from the rest of 1960s sociopolitical engagement, but was consistently involved in and intertwined with other political and social movements such as the civil rights movement, the free speech movement, black power, Chicano rights, the women’s liberation movement, and gay rights. (Good illustrations of this are the graphics of Emory Douglas, the minister of culture for the Black Panther Party from the late 1960s until the party disbanded in 1979–1980.) This was plainly because those involved in antiwar protest activities were routinely involved in protesting other issues during the politically vibrant 1960s, though for many the antiwar movement led to a general political awakening and an involvement in these other issues. Other contemporary movements also provided examples of engagement for the antiwar movement...

- eBook - ePub

Military Spending and Global Security

Humanitarian and Environmental Perspectives

- Jordi Calvo Rufanges, Jordi Calvo Rufanges(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

...8 Peace movement work on military spending Colin Archer 8.1 Introduction Militarism is a big beast. How to hunt it down or at least tame it? Peace movements over the last two centuries have struggled to find the most effective answers. Or to switch the metaphor: it is a mighty tree in a forest of social ills. Is it best brought down by quickly chopping off all its twigs and branches, or can the trunk be axed? Better still, could the whole structure be uprooted? Substitute diverse weapons systems and specific wars for branches; and fundamental causes (inequality, colonialism, machismo, xenophobia, etc.) for the roots, and the significance of the image may become clearer. Around the world many peace campaigners continue to feel that the economic dimension represents the trunk of the tree, and as such is a potent area for struggle against the war system. The economic aspect includes arms research, production and trade; military spending by governments; and indeed the capitalist system itself, seen by many as generative of violent conflict. We shall focus here primarily on military spending, though with some references to related topics, notably the weapons business and disarmament proposals. 8.2 Historical perspective 8.2.1 From 1815 to 1850 Writings against war and in praise of peace are found already in ancient/classical eras and are embedded in all faith traditions. It is worth recalling too that many of the peasants’ revolts in the medieval period were protests against taxation and conscription imposed by kings and feudal lords in order to supply them with the resources to pursue their armed quarrels – and so were in some sense ‘peace protests’. Though not a peasants’ revolt, this grievance was an important element of the celebrated Magna Carta of 1215, imposed on King John by the English barons. However, historians date the beginning of the organised peace movement to 1815 (exactly 600 years later), when the first peace societies were set up in New York and London...

- eBook - ePub

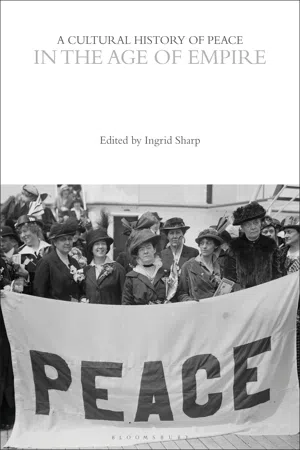

- Ingrid Sharp, Ingrid Sharp(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

...An ideological debate clarified “peace” as an ideal condition whose attainability was, however, disputed; and the revolutions in America and France and the emergence of radical and evangelical pressure politics in Britain demonstrated the possibility of a “movement” promoting such an ideal. What distinguished peace-movement thinking was its rejection not only of the aggressive war which militarists glorified for its intrinsic worth and which crusaders believed could sometimes be a means toward justice but also—and more controversially—of the conventional wisdom that aggression could be deterred by strong defenses. I have treated this last, often summed up in the dictum “if you want peace, prepare for war,” as a distinct ideology called “defencism” (Ceadel 1987: ch. 5) whereas International Relations scholars have tacitly incorporated it into their category of “realism.” Defencism or realism assumed that an armed truce was the best that the international system could expect to achieve, whereas the peace movement was defined by its aspiration toward the more permanent and profound condition of peace that would result from the abolition of war. (This optimism applied primarily to relations among “civilized” states: the extent to which it also applied to the latter’s relations with the colonial world was often left unclear.) There were always two approaches to the abolition of war: absolutist and reformist. The absolutist, for which the word “pacifism” is now best reserved, was the claim that it could be achieved immediately by unconditionally renouncing military force. The boldness of this claim explained its minority status even within the peace movement. Absolutism believed, in effect, that war would be abolished by mass conscientious objection. Its intellectual origins lay in the belief of some Protestant sects that certain social practices, in this case military service, were sinful for them...