British Empire

The British Empire was the largest empire in history, spanning over 20% of the world's land area at its peak in the early 20th century. It was established through colonization, trade, and military conquest, and had a profound impact on global politics, economics, and culture. The empire's legacy continues to shape the modern world in various ways.

8 Key excerpts on "British Empire"

- eBook - ePub

Understanding the Victorians

Politics, Culture and Society in Nineteenth-Century Britain

- Susie L. Steinbach(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

...It was the largest empire on earth. The formal study of the history of the British Empire can be dated to 1882. In that year, Sir John Seeley (1834–1895) published a set of lectures he had developed for Cambridge University undergraduates as a book entitled The Expansion of England. Seeley proposed that scholars integrate the history of Britain’s empire and the history of Britain. His new approach to imperial history mapped onto a new imperialist approach: western powers were beginning to practice a “new imperialism,” in which Britain and other imperialist European powers rapidly claimed large parts of Africa, south Asia, and East Asia. After World War Two, empire became a standard part of the undergraduate history curriculum. The impetus for this change came in part from the work of historians Ronald Robinson and John Gallagher, who co-authored a series of influential works that stressed the power, reach, and influence of Britain on its colonies. They focused on the policies of the British governing elite (“the imperial mind”), on the role of local and indigenous “collaborators” in the governing of empire, and on “informal” as well as “formal” empire, that is, on places and polities Britain controlled via economic domination, even if it had no formal political presence. The Robinson–Gallagher school dominated the study of empire for generations, as imperial historians focused on high politics, the economy, and the role of the military in the expansion of empire. 3 However, since the late 1970s imperial history has changed dramatically. This is due to several developments, including the rise of area studies and subaltern studies, the rise of postcolonial theory, the imperial turn, and the emergence of “the new imperial history.” As decolonization progressed, scholarship began to decolonize and to nationalize as well...

- eBook - ePub

Legal Histories of the British Empire

Laws, Engagements and Legacies

- Shaunnagh Dorsett, John McLaren, Shaunnagh Dorsett, John McLaren(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

...1 Laws, engagements and legacies The legal histories of the British Empire: An introduction Shaunnagh Dorsett and John McLaren DOI: 10.4324/9781315851457-1 In recent years attention has again turned to the subject of empire(s). While previous scholarship often focused on the history of colonies, or of nation states, the newer history of empire focuses on the interconnected nature of the different parts of empire, on the idea of ‘empire’ itself. The ‘boundedness’ of colony and nation has given way to the complexity of the networks of empire. Metropole and periphery have given way to networking, borrowing and transnational history, and the nature of colonial rule has been complicated by accounts of resistance, hybridity and accommodation. Recent work increasingly emphasizes the less formal social and economic connections between the colonies and metropole which are reflected in both activities and initiatives in the colonies and how the colonial experience was internalized in Britain itself...

- eBook - ePub

The British Empire

A History and a Debate

- Jeremy Black(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

...Chapter 3 The Eighteenth-Century Empire The eighteenth century was the period in which key elements of the empire that were later to be highly controversial came to great prominence. This was true both of Britain’s establishment of a significant territorial position in India and of its dominance of the Atlantic slave trade. These developments did not exhaust the long-term importance of the century. The cohesion of an English-, indeed London-, dominated British Isles was ensured with the defeat of Jacobite risings in Scotland and northern England in 1715–16 and 1745–46, and with the suppression of the Irish rebellion of 1798. Alongside, as a result of defeat in the American Revolution, the loss of the Thirteen Colonies that became the basis for the modern USA, these contradictory developments serve as a reminder that the empire was contested not only by foreign powers, most prominently France, but also by native as well as by settler opposition. Indeed, the response to opposition to imperial control became, with the American Revolution, an important aspect of the debate within Britain about the purpose, effectiveness, and future of the British Empire. This opposition could overlap with the debate. Moreover, the aftermath of these rebellions, notably in Scotland and Ireland, is an important aspect of the contested legacy of empire. The eighteenth century witnessed the continuation of earlier developments, but also two highly significant changes that, between them, greatly altered the character of the empire. The establishment, in mid-century, of a major British territorial position in India, notably in the prosperous region of Bengal, looked towards nineteenth-century expansion, there and in Asia as a whole. Conversely, the loss, in 1775–83, of the Thirteen Colonies represented both a major challenge and also a departure from the position that the empire included the extensive British diaspora, or, at least, the Protestant diaspora...

- eBook - ePub

Imperial Meridian

The British Empire and the World 1780-1830

- C. A. Bayly(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

...Yet it has been overplayed by a reductionist and empirical historiography which always saw nationalism as a dubious enthusiasm to which foreigners were prone. This study has therefore supported Vincent Harlow in his view that there was a 'Second British Empire' emerging more rapidly after 1783, and that it differed in important respects from the earlier empire of colonies. Except during the immediate aftermath of the Seven Years' War, the pace of imperial expansion had earlier been governed by change outside England. In Asia the consequences of commercialisation and the formation of new states had indirectly drawn the servants of the East India Company into great acquisitions in Bengal and Arcot. The pace of British expansion was related to the slow 'crisis of proto-capitalism' in the great Muslim empires. In the West Indies and Canada wars of monopoly and mercantilism had given opportunities to Creoles to hamstring their French or Spanish enemies. After 1783, however, the role of England in empire-building was strongly reasserted. We would agree with Hopkins and Cain that the economic value of empire to Britain continued to lay much more in its contribution to finance and services than to the emerging industrial economy. However, empire itself transcended the confines of 'gentlemanly capitalism', becoming for the critical span of years up to 1830 a patriotic and godly project forged in the context of international ideological and social conflict. And while Anglicanism did indeed inform this empire at important junctures (Clark 1985) it was in the context of a reinvented and refounded consensus of national élites, not the persistence of an ancient absolutist tradition. The aim of this book, however, is not simply to enshrine the 'metropolitan element' once again, whether this be gentlemanly capitalism or aristocratic militarism. Empire by definition was a dialogue between metropolitan impulses and the history of the colonised societies...

- eBook - ePub

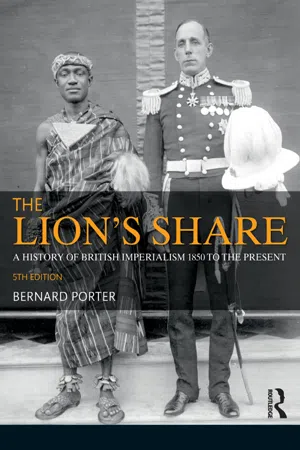

The Lion's Share

A History of British Imperialism 1850-2011

- Bernard Porter(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

...2 An empire in all but name: the mid-nineteenth century The world market T he term ‘empire’ had its origin in a Latin word associated with notions of ‘command’ or ‘power’. Generally, however, its meaning has been a little more specialised – though not much more. It was never a definitive or generic term like ‘republic’ or ‘democracy’. Its usage was determined more by historical accident than by semantic design. Usually it could mean one of two things. It could mean simply the country presided over or the authority exercised by a ruler who happened to be called an emperor. Or, more helpfully, it could mean the territorial possessions of a state (whose head might or might not be styled ‘emperor’) outside its strict national boundaries. It was in this latter sense that Britain and her overseas territories in the late nineteenth century together comprised an empire. On the surface this empire seemed an uneven and inconsistent kind of political entity, as indeed it was. Its different constituents were united in very little apart from their common allegiance to the British crown. Even the degree of this allegiance, the extent to which the Queen’s ministers could presume on a colony’s loyalty for help in a crisis, varied in practice from one part of the empire to another. There was no single language covering the whole empire, no one religion, no one code of laws. In their forms of government the disparities between colonies were immense: between the Gold Coast of Africa, for example, ruled despotically by British officials, and Canada, with self-government in everything except her foreign policy, and here London’s control was only hazily defined...

- eBook - ePub

The Ascendancy of Europe

1815-1914

- M.S. Anderson(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

...It is important to remember, moreover, how little Britain’s unofficial and even her official empire in these decades depended, at least directly, on her army and navy. Little of her own limited military strength was committed on a regular basis to Asia or Africa and none to Latin America. It was at least as much the support of local elites and forces – Indian princes, sepoy troops, Brazilian or Argentinian landowners – which made possible this imperial growth. All this expansion, open or covert, official or unofficial, amounted to a very formidable growth of European territorial and economic power, above all in Asia and the Near East. Whereas in 1835 seventy British naval vessels were serving on non-European stations, twice as many, with a third of the total establishment of seamen and marines, were doing so a generation later. 11 Certain moments saw displays of British world power of a completeness scarcely possible before. Such were the few days in December 1840 which saw the almost simultaneous arrival in London of news of the capture of the Chinese island of Chusan, of a victory in Afghanistan and of the conclusion in Alexandria of the agreement by which Mehemet Ali acknowledged the defeat of his ambitions in Syria and Asia Minor; or the few months in 1857 when Britain crushed a great military revolt in India, sent an expedition to the Persian Gulf and thus forced Persia to renounce her territorial ambitions in Afghanistan, and captured Canton from the Chinese. Yet in no case was imperial expansion before the 1870s the result of a consistent and wholehearted demand for it in the European state concerned. Sometimes it was the outcome of an incoherent striving for national status...

- eBook - ePub

Property, Land, Revenue, and Policy

The East India Company, c.1757–1825

- J. Albert Rorabacher(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

...It was an imperial possession of the East India Company, and later Great Britain, but it was not a colony. As Angus Maddison has pointed out, at no time did the Company consist of more than 4,000 European expatriates. 25 With very few exceptions, every Company employee and civil servant stationed in India, returned to England. Without a sizeable number of expatriates intent on remaining permanently in India, India cannot be deemed a colony. Colonialism includes the individual and collective intent to remain in and permanently occupy a territory outside one's native land, one's homeland. India was simply an imperial possession. The Company and the British Government only exercised imperial dominance over India. It was conquered and controlled - politically and economically but it was not colonized. To say India was a colony is just too loose an interpretation of the term colonialism. Philip Francis, one of the early framers of Permanent Settlement in Bengal, understood the British position and role in India. 'Considering the country as our estate, there is no other way to make it productive' England was thus required to assume responsibilities of an improving landlord in Bengal. The distance between the two countries and the inadvisability of colonization made it necessary that the property should be entrusted to the care of a class of native entrepreneurs who had solid interests in the land and were politically reliable. This alone could establish the permanence of dominion'. 26 With far fewer people than existed in any of the Indian provinces, the American revolutionaries were able to topple the British imperial structure in North America. At least in theory, this could have menaced the entire British Empire, for it provided a template for the elimination of British imperial domination. Had there been a national will in India - a national identity - the British could easily have been expelled from India at any time...

- eBook - ePub

- Patrick Truck, Patrick Truck(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

...1 BRITISH EXPANSION IN INDIA IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: A HISTORICAL REVISION DOI: 10.4324/9781003101024-1 Peter Marshall The conquest of the Indian sub-continent in the hundred years from the mid-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century fits awkwardly into most histories of the British Empire as a whole. 1 Older views which believed that the loss of the American Colonies had been followed by a long period of imperial disillusionment and the avoidance of fresh commitments may have been substantially modified in many respects, but it is still undeniable that a series of annexations of huge and often densely populated new provinces went against the grain of many assumptions widely held in the century of conquest. For about seventy-five of the hundred years, historians trying to reconcile theory and practice do at least have the advantage of being able to identify the persons on the British side who took the decisions that led to conquest. From about 1784 a clear chain of authority was established: in London the Board of Control was set up through which the ultimate responsibility of ministers came to be asserted, while in India the Governor General was given overall control. After 1784 it is therefore possible for historians to argue more or less plausibly about coherent British policies being applied in India and to attempt to account for them. Before 1784 this is not possible. Authority was divided at home between the national government and the East India Company; control from Britain over Englishmen in Asia was very tenuous; and in India the British settlements were more or less independent of one another and their Governors’ powers were relatively weak. British ‘policy’ towards India before 1784 is thus likely to be an elusive concept. Yet by 1784 Britain had won a substantial Indian empire in both ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ terms...