![]()

1

Motherless Child, 1901–19

Raised believing freedom was something you fought to win, Langston Hughes was brought up by his maternal grandmother Mary Langston in Lawrence, Kansas. The nearly seventy-year-old woman, whose own mother was Cherokee, left her home in Fayetteville, North Carolina, for Oberlin, Ohio, after men attempted to enslave her at the age of nineteen. Quite symbolically, James Langston Hughes was born on 1 February 1901, nearly sixty years before the Greensboro sit-ins started and Black History Month’s official inception. It was only recently discovered that his birth year was actually a year earlier than had been previously believed by everyone (including Hughes himself).1

Named after his father, whom Hughes hated, his first name was quickly abandoned. Jim Hughes was a frustrated businessman who had two white fathers in his bloodline. His rushed marriage to Carolina ‘Carrie’ Langston in 1899 amid rumours of a ‘shotgun wedding’ eventually resulted in their infant child dying of unknown causes.2 Leaving Guthrie, Oklahoma, months before their only other child was born in Joplin, Missouri, the couple’s frequent moves throughout the Midwest set in motion a life of travel. Hughes led a blues lifestyle, learning early on that home was a place you left.

The writer would state: ‘My theory is that children should be born without parents – if born they must be.’3 Hughes felt this way as his own father left immediately after he was born on extended trips to Buffalo and Cuba before settling on his own for good in Mexico. Though trained as a teacher, Hughes’s mother Carrie was forced to relocate away from her child as she took odd jobs as a maid or janitor while longing for a successful stage career that never materialized.

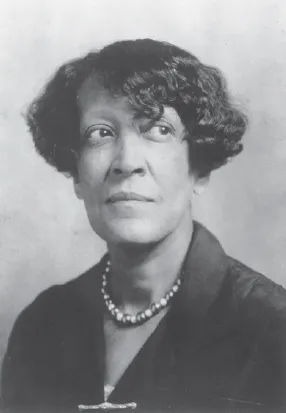

The almost seventy-year-old Mary Langston, c. 1910, around the time she was raising Hughes in Lawrence, Kansas. Not only had Mary fled North Carolina in her youth when men tried to enslave her, but she inspired Hughes with her stories of real-life heroism, including the death of her husband Lewis Leary as he fought with John Brown at Harpers Ferry in 1859.

Hughes came from a family with a very storied past. The roots to his family tree are so tangled that it is often difficult to distinguish which branch each one feeds. His grandmother Mary would place a shawl over young Langston as he slept at night, reminding them both of the rich heritage of their ancestors. Langston was told that the shawl had been worn by Mary’s first husband, Lewis Sheridan Leary, who died with John Brown at the raid on Harpers Ferry. The nine-year-old Hughes was filled with awe at the story of the valiant attempt to free slaves when he saw his grandmother seated with distinction at a dedication ceremony where President Theodore Roosevelt spoke.4 Mary’s second husband, Charles Langston, had halted fugitive slave John Price’s return to the South in the very public 1858 Oberlin–Wellington rescue. Excelling while breaking conventions, John Mercer Langston, Charles’s younger brother, not only had a city and college in Oklahoma named after him, but was the first vice president of Howard University and served as a Virginia Congressman in 1890.5 Charles Langston’s father Ralph Quarles had lived with former slave Lucy Langston as man and wife and they are buried as close as custom allows, still facing each other on opposite sides of a segregated cemetery.

| Langston Hughes, age three, around the time he started sleeping under a shawl he believed was worn by Lewis Leary when he died. |

Carrie Hughes Clark, c. 1925, was often working and returned to win key battles that kept Hughes in school, even as she dreamt of a theatre career that never came to pass. | |

Carrie came and went. When she was back at home, she took her son to see plays such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Buster Brown in places as far away as Kansas City, and Hughes developed his love of theatre from her.6 It was in Kansas City where he heard his first blues: a performance by a blind orchestra where the music ‘seemed to cry when the words laughed’.7 Well before he transposed them into new poetic forms, he wrote down many of the songs he heard, and some would inadvertently be attributed to him as poetry he himself wrote:

I’m goin’ down to de railroad, baby,

Lay ma head on de track.

I’m goin’ down to de railroad, babe,

Lay ma head on de track –

But if I see de train a-comin’,

I’m gonna jerk it back.8

Working about 96 kilometres (60 mi.) away in Topeka as a stenographer for the black-owned and -operated newspaper the Plain Dealer, Carrie sought to briefly enroll her son under her own care for his first year of school. Her uncertainty about where he might attend school – Topeka, Lawrence or even Mexico City – may be the reason she shared his birth year as being later than it actually was. Making the extra year known might have resulted in either her or her son standing out in unwanted ways. When Langston was sent across the tracks to the segregated school, she argued with the white school principal and won (four decades before the city would become famous for Brown v. Board of Education in 1954). Before Carrie returned him to Mary’s home in Lawrence and headed off to work in Colorado Springs, Langston endured hearing his first teacher tease the children that they should not eat liquorice because it would ‘make you black like Langston’.9

Life with Mary Langston included stories from the Bible, hymns, Grimm’s Fairy Tales, and every newspaper and magazine she could afford. She told him stories of Haitian heroes while he sat on a stool or ‘stretched out on the floor, staring up at the stars’.10 Her work as part of the Underground Railroad and education as one of Oberlin College’s first African American students left him hearing ‘tales of heroism, of slavery and freedom, and especially of brave men and women who had striven to aid the colored race’.11

When Mary died in 1915, Langston lost a woman whose eyes were as wise as an owl’s. Whe he was fourteen, he went to live with close family friends, James and Mary Reed, a couple he knew before his grandmother’s death. With Auntie Reed, Hughes drove the cows, set the hens and ate ‘wonderful salt pork greens with corn dumplings’.12 Often sporting a chequered flat-cap on his head and wearing knickerbocker pants, he found that eating from their garden was a substantial improvement over the dandelion greens Mary had served. The poet probably conflated the two women when he wrote ‘Aunt Sue’s Stories’:

Aunt Sue has a head full of stories.

Aunt Sue has a whole heart full of stories.

Summer nights on the front porch

Aunt Sue cuddles a brown-faced child to her bosom

And tells him stories.13

Hughes starting delivering newspapers at about the age of thirteen. Pages of the Saturday Evening Post, Lawrence Democrat and the leading socialist weekly in America, Appeal to Reason, arrived in mailboxes and doorsteps from the hands of Langston Hughes.14 While delivering papers would be a common first job for many, the activity must have held special meaning for Hughes as he would eventually both write news articles sent from the Spanish Civil War and have his own weekly column in the Chicago Defender for more than 22 years, where he used humour as a weapon to attack racism in every form. More people read Hughes’s newspaper columns during his lifetime than his books of poetry.

Seventh grade in Lawrence also provided another formative experience. When his teacher segregated the few black students in the class, Hughes created cards that read ‘JIM CROW ROW’ and placed them on each of his black classmates’ desks. When the teacher challenged him, he ran out onto the school grounds, repeating over and over that his teacher had a ‘Jim Crow row’. Summarily expelled, community leaders joined his mother in getting him reinstated with one significant change when he returned: the classroom no longer had any Jim Crow row.15

| Langston, c. 1910. Often seen delivering newspapers around Lawrence, young Langston grew up in mostly white schools and neighbourhoods, accepting work such as cleaning out brass spittoons. |

Hughes, in 1915 at the age of fourteen, took a lowly job at a white hotel where he worked for 50 cents a week cleaning the lobby. The work included the task of cleaning out the ‘Brass Spittoons’, something Hughes would put into verse: ‘Clean the spittoons, boy’, where ‘the smoke’ and ‘the slime’ become ‘Part of my life’.16 Whatever humiliation he felt in such degrading work, it prepared him for the jobs he was to take later when he sailed the world in his twenties as a deck-hand. More importantly, cleaning never compared to the pain he felt after a decisive church revival gathering; believing he would literally see Jesus, as his Aunt Reed said he should, only young Langston and a friend remained unsaved at the front of the church. When the friend walked away only pretending to be changed, Hughes was all alone, unable to fake the experience he was sincerely expecting. Stone still, he eventually answered two questions when the preacher agonizingly approached and was thereby hailed as ‘converted’. That night he wept anything but tears of joy. He felt he had lied, been lied to and, worst of all, that Jesus had passed him by, not caring enough to appear before his waiting eyes.17

Hughes never forgot this painful experience at Aunt Reed’s St Luke’s African American Episcopal (AME) Church. Yet it did not inhibit him from writing numerous religious plays, especially d...