![]()

PART 1

![]()

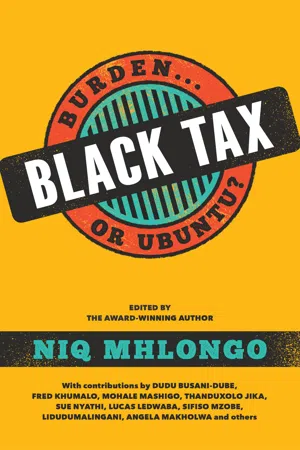

Black tax – what you give up and what you gain

Dudu Busani-Dube

I was going to try and humour you, until I realised, I had no right.

I was going to tell you about my petty ‘black tax’ experiences which, after I had sat down and thought about, I found more funny than frustrating. I was going to tell you about the many times I’ve gone to fetch my mother from church and ended up with four of her mates on my back seat whom I’ve had to drop off at their houses, spread across the whole township of KwaMashu. One of them might want to pass by the local Shoprite to buy something while the others wait in my car with their arms folded, firing off questions like when am I having a baby and am I taking good care of my husband.

Where I come from, everyone old enough to be your parent is your parent. They also raised you and saying no to them is not an option, which is why you pay your black tax without whining, whether it is by emptying your petrol tank driving them around or accommodating their children in your house when they come to Joburg for job interviews.

I was going to tell you how, even though my parents have a three-bedroomed house and only my brother and I lived with them – though we were five children in total – I never had my own bedroom. I assume that when they bought the house, they figured it was going to be big enough for their small family with their bedroom, my bedroom and my brother’s bedroom but no … that turned out to be a far-fetched dream.

For as long as I can remember, my parents’ house was always some kind of ‘halfway house’ where every family member – immediate or extended – could stop and stay while trying to find their feet in Durban. There were also children of neighbours, from the village where my father was born, who passed through; some from my mother’s side of the family and, at one point, a woman called Eggy, from Lesotho. I still don’t know what that was about.

Most of these people have gone on to become something in life. Today, many own even bigger houses than my parents’. So it dawned on me that my parents have been paying black tax from before I was born. Only, in their time it was about ‘breaking the cycle’.

I wasn’t sure about my contribution to ‘breaking the cycle’ and it bothered me, so I called my father, a 64-year-old retired primary school principal, who shocked us seven years ago when he announced he was retiring at 57.

‘I’m tired,’ he simply said when asked about his reasons.

When he made the announcement, my brother was 23 and already grown-up and I had also been working for years, so a part of me understood why father was tired. I have always known he had a difficult life growing up. He had seven siblings of whom he was the second eldest.

When I called him, I asked him a few basic questions like, ‘Baba, what was the first thing you did for khulu when you started working?’

‘You mean when I was ten years old?’ he asked.

I was climbing trees and eating bread with jam when I was ten, so his question didn’t make sense to me. ‘No, when you started teaching at your first school in Mzinyathi,’ I said.

He explained to me that, actually, his first job was somewhere in Stanger when he was about nine years old. He worked for a white man without knowing what his specific job description was, he just did as he was told.

I didn’t know this.

I also didn’t know that he only started school when he was ten and that, while going to school, he worked at the village hospital on weekends, where he earned 25c a week.

‘With the money I made, your grandmother bought a goat and that goat had lambs and that’s how we got to have livestock.’

I remember there were goats at my grandmother’s house in the five-year period during which I lived there as a child. There was a house, too, which we called ‘endlini enkulu’. It was a mud house, but it had a good shape and on the inside there was a set of sofas, a table and dining room chairs.

‘We built that house when I started working, with the salary I earned in the first three months. It was three hundred and something, I was earning R125 a month.’

The ‘we’ includes his late elder brother, who didn’t go further than lower primary school because he was the eldest and had to work to support the family.

I wanted him to tell me more, but I could feel him withdrawing. He ended the conversation with ‘Ayixoxeki le, but it made us men.’

My father, being of an older generation, wasn’t familiar with the term ‘black tax’ and heard it for the first time during our conversation. This, of course, is very telling. I found that I could not explain it to him, lest he found it offensive because to him helping others was a responsibility, something that automatically came with being an elder sibling. I feel equally uncomfortable with this term.

My father made it to a teaching college with the assistance of the Lutheran church and was appointed principal before he turned 35. Judging by what he had to go through to get there, he was very successful, and in our community, success comes with expectations, it comes with the responsibility to send the elevator back down to fetch the others.

After hearing my father’s story, a part of me still wanted to whine a little bit about black tax and how it isn’t really necessary in this day and age. After all, aren’t we out of the dark ages now, with opportunities available to everyone?

And so, I found myself having this conversation with my elder sister, the daughter of my father’s brother, who has made my life very difficult by doing everything right and instilling in me a fear of failure. When I mentioned black tax, she said, ‘Weeeeeeeh, you should have prepared me for this.’

I couldn’t see her at the other end of the line, but I could picture her with her hands over her head as she said this. She is the eldest of the more than 25 grandchildren – the loudest, the feistiest and also the one who fully understands the poverty our family comes from and has carried it on her shoulders since she was a child.

There wasn’t any money for her to go to university, brilliant as she was, and so she waited two years before she was accepted into a government nursing school which afforded her an opportunity to do her degree at the University of Zululand. She immediately sent the elevator back down with the R1 800 student-nurse stipend.

First, you take care of home. That’s a rule of black families that doesn’t need to be written down. She built a two-bedroomed brick house for her mother, opened an Ellerines credit account and bought the first sofas and a fridge. She told me this without an ounce of bitterness in her tone. I didn’t understand how.

While the rest of the adults in our family were taking care of everyone else, she was taking care of me and her younger siblings. To me, she was my sister with a job, and that meant I could get clothes from her. Her student residence at the hospital was where I went for vacation during school holidays. The best time of my life because I could sit around doing nothing all day and eat as much as I wanted, while she was out studying during the day and sometimes working at night.

Now we go on holidays together, dine in fine restaurants and steal each other’s clothes, but the subject of how much we delayed her journey to such a life never comes up. We don’t need her money anymore, but where would we be without the R1 800 she had to split amongst us?

In the same vein, where would those many people be had my parents closed their doors to them and decided it’s each man for himself?

Black tax is a sensitive subject. We are not prepared to explain it to people who can never understand the depth of it and we never will, just ask that other bank that once tried us on this matter. This is also why we black people can joke about it, but will immediately go into attack mode if a white person even tries to join the conversation; because we are the children of domestic workers and gardeners, we have no ‘old money’ and nothing to inherit.

It comes with some anger, too, and no, it is not directed at the families we have to take care of, but at the system that was created to ensure that no matter how much freedom we think we finally have, it will still take us decades to crawl out of the dungeon we were thrown in.

We still laugh about it, though, just like we laugh about land, sometimes.

Black tax isn’t our culture, no, it isn’t. It has everything to do with the position this country’s history has put us in. It is not even entirely about money. It begins with the sacrifices we have to make because of a lack of money.

Black tax is being a 19-year-old varsity student at res, with nothing to eat, but then not calling home to ask for money because you know there isn’t any.

Black tax is earning a big enough salary to buy your first car, but you can’t because the bank loan you took to fix your parents’ dilapidated house landed you at the credit bureau.

Black tax is not having an option to take a gap year after matric because what is that, anyway?

Black tax is opting to go for a diploma when you qualify for a degree, because a diploma takes only three years, and hopefully you’ll get a job after that and take over paying your siblings’ school fees so that your mother can maybe quit her job at that horrible family she is working for in the suburbs.

Black tax is understanding that you can’t stay at varsity full-time to do your honours and master’s because NSFAS (the National Student Financial Aid Scheme) might not pay for it.

Black tax is the anxiety you have before a job interview because your township-school English might just humiliate you and cost you a career opportunity.

Black tax is being in Johannesburg and trying very hard to hide your struggles from your family back in Mtubatuba, or Qonce, because you don’t want them to worry.

Black tax is your mother having to change the subject every time the neighbours ask her why her paint is peeling and her geyser broken when she has an employed daughter.

Black tax is all the shit that plunges us into depression and forces some of us to live a lie.

It’s not our parents’ fault, they had it even worse. They fought and died and paid their fair share to get us to where we are. Most of them never even ask for the things we offer them.

Black tax is also the biggest enemy of marriage and a source of sibling rivalry. Some of us enter marriage carrying large financial responsibilities on our shoulders. Just think about it, wha...