![]()

1 INTRODUCTION

I have before me a series of fashion engravings dating from the Revolution and finishing about the time of the Consulat. These costumes, which cause much amusement amongst many thoughtless people—solemn people who lack real gravitas—have a dual charm both artistic and historical. They are often beautiful and drawn with wit but what matters as much to me and what I am happy to find in all, or almost all of them, are the moral and aesthetic values of their time.

(BAUDELAIRE, THE PAINTER OF MODERN LIFE 1968 [1863]: 547)

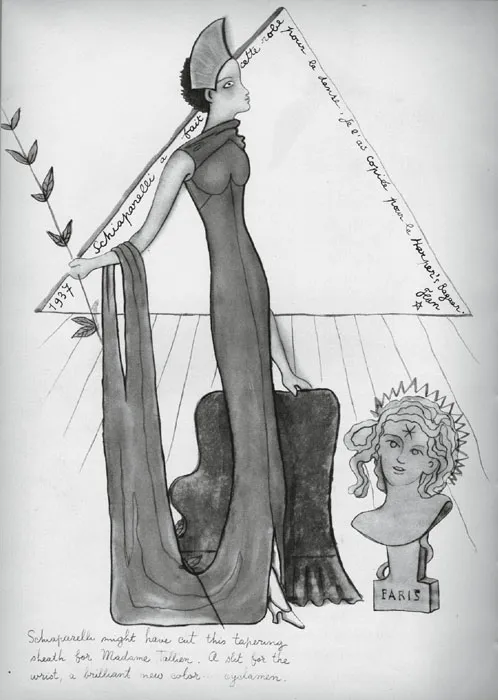

I confess, I am as charmed by the sight of fashion on the page as Baudelaire. I have spent many hours writing about fashion journalism, even more time researching it, and more time than I care to remember consuming and enjoying it. I am not alone in this: artists from Manet, Cocteau (figure 1.1), and Klimt to Damien Hirst, photographers such as Man Ray and Deborah Turbeville, and writers from Honoré de Balzac and Oscar Wilde to Dorothy Parker, Angela Carter, and Linda Grant have all been fascinated by writing about and images of fashion. This is no mystery to me because, as I will endeavor to show, fashion journalism cannot be seen as being separate from fashion itself. The two are symbiotic. As an integral part of the fashion system, fashion journalism reflects all of the variety and creativity of fashion. Indeed, if fashion is the creation of the symbolic value of clothing, then the fashion media—dedicated magazines, fashion columns in newspapers, women’s “service” magazines, Sunday supplements, hybrid or niche magazines, television, and blogs and other online platforms—have been, since the outset, at the very heart of the process. This is the argument proposed by Roland Barthes in his seminal work on French fashion journalism, The Fashion System (1990 [1967]). Although Barthes was not an enthusiast of fashion journalism, his exploration of late 1950s’ magazines provides a useful point of departure for an analysis of the fashion discourse. Barthes suggested that fashion journalism has shaped, and possibly even created, the concept of fashion and its symbolic value.

FIGURE 1.1 Cocteau Illustration of Schiaparelli Dress, Harper’s Bazaar 1937. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2016. Image courtesy of Fashion Institute of Technology/SUNY, Gladys Marcus Library Department of Special Collections.

Furthermore, if fashion is a protean and ambivalent subject, fashion journalism has, since Le Cabinet des Modes in the eighteenth century, been responsible for harnessing this mercurial goddess into a comprehensible and desirable system. Fashion functions paradoxically as a marker both of individual identity and of an individual’s relationship to the group. Fashion journalism has from the beginning served to bridge this gap, democratizing fashion but at the same time upholding its discriminatory and symbolic value (Bourdieu 2010 [1984]).

Nor is fashion journalism simple writing about fashion. As Baudelaire observes, it holds up a mirror to broader culture, acting as a hinge between the fashion industry and public consciousness (Wilson 2003 [1985]: 157). Fashion journalists thus function as ‘gatekeepers’ who often identify and anticipate dramatic shifts in the broader culture (McCracken 1986: 77), as was the case with the Kate Moss cover of The Face (plate 14), which signaled a shift away from glossy designer imagery. In addition, since the appearance of Le Mercure Galant in the seventeenth century, fashion writing has also made a significant contribution to ideological history and cultural norms, particularly where women are concerned. It has helped shape not only views of beauty and femininity but also attitudes toward consumerism and even national identity. The fashion media have also been at the forefront of developments in marketing, image making, and publishing.

Fashion journalism is increasingly recognized as a discipline. Today it is the subject of professional courses and degrees at the likes of Pennsylvania State, the University Of Michigan, and Rutgers University, as well as specialist fashion institutions such as FIT and The London College of Fashion. Fashion journalism is also the most popular specialism on more broadly based media studies courses (Bradford 2015: xii). However, there has never been a study dedicated solely to an analysis of the historical form and content of the fashion discourse. This is the gap The History of Fashion Journalism aims to fill.

For some critics, writing about fashion lacks journalistic integrity because of its close link with the fashion industry itself (Robin Givhan is the only fashion journalist to have been awarded a Pulitzer Prize). In this view, fashion writers and magazines are little more than what Friedman calls “cheerleaders” (2014) or others, less generously, “PR poodles”: their job is to encourage readers to buy clothes and thus to keep the fashion industry—and themselves—in business. As sociologist Brian Moeran has noted, fashion magazines are both cultural products and commodities (2008: 269) and therefore inevitably mediate tensions between their artistic, ideological, and commercial agendas. As we will see, however, this has not precluded aesthetic innovation, ideological insight, and cultural influence in fashion journalism. Again, I would argue that it is precisely the inherent tensions born of its close relationship with the fashion industry that makes fashion journalism so rewarding a subject of study.

Above all, when considering the value of fashion journalism, I think it is worth considering this question. If it really is as trivial as its critics allege, why did Hitler work so hard to muzzle the French fashion press during the German occupation in World War II (1939–45)?

A crisis of identity?

Fashion is a $1 trillion global industry (Tungate 2012 [2005]: 1). The fashion media are just as global and have their own impressive figures. In 2015 Vogue had an international print audience of 12.7 million and 31.1 million monthly unique users of its website (condenast.com), while the Louis Vuitton 2015 cruise collection, which was showcased at Bob Hope’s Palm Springs mansion, nearly crashed Instagram. Fashion has arguably become the global discourse, with more media coverage than any other similar subject (Polan 2006: 154), stretching from the blog of America’s First Lady, Michelle Obama, to coverage of emerging fashion centers such as Nigeria. Fashion is the subject of movies and TV shows and webcasts of “behind the scenes” films, while designers have crossed disciplines to open hotels (Missoni, Armani), collaborate with food manufacturers (Coca Cola, Pepsi), and open art foundations (Prada, Louis Vuitton).

As the reach of fashion has grown, so has that of the fashion media: ‘Today newspapers, fashion magazines, television programmes, and the internet bombard us with information and advice on dress and appearance. We are saturated with images of fashion’ (Wilson 2003 [1985]: 248). Traditional print journalism has been challenged by cinema, television, blogs, live streaming of catwalk shows, celebrity and designer social media, fashion film, and online retailers as sources of fashion information and inspiration. Commercial pressures and conglomerate power have left some journalists feeling ‘just garnish for PRs and designers’ (Cronberg 2016). For some observers, such developments—combined with the increasingly rapid fashion cycle whereby clothes are on the high street before fashion journalists have a chance to opine on them—have brought traditional fashion journalism to a crisis point. As early as 2004 Stéphane Wargnier, then director of communications at Hermès, argued that contemporary fashion journalism was weakened by a ‘loss of identity’ (Wargnier 2004: 164–5). This begs the question of exactly what that identity is, and what has been the historical function of the fashion media.

Toward an approach: Key themes

Despite widespread academic and public interest in fashion itself, fashion journalism—with the exception of fashion photography and illustration—has remained somewhat marginalized.1 However, there has recently been more engagement with the development of the fashion media, most notably: Breward (2003: Chs 4 and 5); Polan (2006); Bartlett et al. (2013); Bradford (2015) and McNeil and Miller (2014). The History of Fashion Journalism forms part of this engagement by providing a historical overview of the industry and its development from its origins up until the present day. Focusing on the specialist fashion media, it will also look at the expanded coverage of fashion in newspapers since World War II and the advent of color supplements in the 1960s—many of the industry’s “grande dames,” such as Eugenia Sheppard, Hebe Dorsey, Ernestine Carter, and Suzy Menkes, were and are newspaper based—as well as its expansion to television and the internet. It does not claim to be exhaustive but aims to cover the highlights and major changes in both format and content, and to act as a reference and springboard for more detailed research.

Such an overview suggests that the principal functions of fashion journalism have remained largely unchanged since the seventeenth century, although their reach and scale have developed alongside the industry.

Cultural arbiters

Vogue’s website claims that the brand’s authority is founded on its role as a “cultural barometer for a global audience” (2015). The starting point of this history is this relationship between fashion, its media, and culture, as examined also by commentators as varied as Baudelaire and Barthes. So successful has journalism been as a “cultural barometer” that some observers, such as Gilles Lipovetsky (1994 [1991]), would argue that fashion is at the heart of modern culture and, indeed, Western democracy.

The traditional role of fashion journalists has been as cultural arbiters who “review aesthetic, social and cultural innovations as they first appear and then classify these innovations as either important or trivial” (McCracken 1986: 77). Journalists then pass on their views to readers (ibid.), making them what Wargnier calls “social mediators” or “spokespersons for the spirit of the time” (2004: 165). This link between fashion and culture is the mechanism journalists use to create what Barthes calls “the fashion effect”: in other words, fashion (1990 [1967]: 17). Indeed, Barthes argues that it is only from this dialogue with broader ideological values that fashion acquires its meaning (ibid.: 218). Of course, neither this meaning nor fashion’s symbolism within culture has remained stable: at certain points, such as the mid-nineteenth century in France, for example, fashion has come to symbolize everything that is happening in society. Furthermore, it does not always translate across national boundaries. Shifts in values are reflected in both imagery and text and, indeed, in the shifting relationships between them.

In their 2014 book, Fashion Writing and Criticism, historians Peter McNeil and Sanda Miller explore the importance of “taste” as a criterion for judging fashion in the eighteenth century. The notion of taste later disappeared as the key signifier in fashion judgment, replaced by a new lexicon that reflected changing cultural values. The new touchstones included “smart” and “chic” in the 1920s, “elegant” in the 1950s, and “style” in the 1980s. For some observers, the fact that contemporary fashion writing lacks such recognized touchstones is a sign of a lack of evaluative appraisal.

A symbiotic relationship

As noted earlier, the relationship between the fashion media and the industry is symbiotic: as the industry changes so does its journalism, and sometimes vice versa. Essentially, however, it remains commercial in nature: “Fashion, the described garment encourages the purchase” (Barthes 1990: 17), or as Anna Wintour once put it, “Vogue’s not here to burst the bubble; it’s here to sell, sell, sell.” The eighteenth-century use of advertorial—advertising masquerading as editorial—was an early example of this business agenda. Later in the nineteenth century magazines both supported and were supported by department stores, in the 1950s and 1960s by fabric manufacturers, and in the 1980s by the menswear business.

The promotional relationship between the industry and its media is one of the central themes ...