eBook - ePub

People's Capitalism?

A Critical Analysis of Profit-Sharing and Employee Share Ownership

Lesley Baddon,Laurie Hunter,Jeff Hyman,John Leopold,Harvie Ramsay

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 332 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

People's Capitalism?

A Critical Analysis of Profit-Sharing and Employee Share Ownership

Lesley Baddon,Laurie Hunter,Jeff Hyman,John Leopold,Harvie Ramsay

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

First published in 1989. In the decade before this book was originally published, employee share ownership and profit sharing had increased markedly as successive governments introduced fiscal legislation promoting their uses. Yet how successful had 'people's capitalism' been?

The Glasgow study was a major empirical investigation into this issue and was a response to the need for an independent assessment. It discusses how attitudes to ownership had changed and how these, in turn, related to attitudes to work. It also addresses the implications of profit sharing and employee share ownership for industrial relations both for individual companies and at a national level.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es People's Capitalism? un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a People's Capitalism? de Lesley Baddon,Laurie Hunter,Jeff Hyman,John Leopold,Harvie Ramsay en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Negocios y empresa y Negocios en general. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Part 1

The profit-sharing debate

1

Introduction to the debate

BACKGROUND

Though the surge of activity in debate and practice over employee participation in organizational decision-making which peaked in the 1970s has subsided to more sober levels, continued interest in the subject has been maintained, but with a somewhat altered focus, reflecting changed political and economic priorities raised during a period of prolonged economic recession and trade union weakness. A significant expression of this change has been the shift in emphasis from representative forms of involvement, typified by the Bullock proposals for the appointment of worker directors, to participative strategies which aim at more direct contact between management and individual employees. A reflection of this approach can be seen in recent pronouncements by the Conservative government encouraging direct communication between organization and individual, linking the development of a shared culture of enterprise and initiative with the rewards which may be anticipated in consequence:

The Government is completely committed to the principle of employees being informed and consulted about matters which affect them. Our future industrial competitiveness and prosperity depend on both employers and employees having the same belief and commitment to make employee involvement work … [Gummer, 1984, quoted in Cressey et al., 1985: 7]

Employee involvement can take many forms. In the research reported in this study we are mainly concerned with financial participation, which can be divided for our purposes into two broad categories: profit-sharing, in which employees are given the opportunity to take some of their income from employment in a form related to the profits of their employer; and share ownership, in which employees are enabled to acquire some degree of ownership over the assets of the employer. For reasons that will emerge, this distinction is one that has to be quite firmly drawn from the outset, since the two forms generally have rather different implications for motivation and behaviour within the participative framework.

Though profit-based remuneration has a long history, the take-up of schemes involving a measure of financial participation has historically been low in the United Kingdom, both absolutely and in comparison with some of its industrial competitors. The first identifiable phase of profit-sharing occurred in the middle years of the nineteenth century, when the experience of the Henry Briggs company generated considerable enthusiasm among sympathetic employers. There is little doubt that this initial phase of profit-sharing and its less common share ownership offshoot were introduced primarily as a means to prevent or inhibit union activity: indeed, the Briggs company only turned to its new profit-sharing ‘tactic’ following the failure of more traditional aggressive tactics in combating union recruitment and activity (Church, 1971: 5). Other schemes launched during this period often masked similar intent: some prohibited ‘workmen’ from union membership and most restricted bonus entitlements to employees whose individual and collective behaviour was deemed to be satisfactory. A prime consideration for implementing these early schemes was to contain collectivist pressures and for this reason schemes were often withdrawn when profits declined and with them, the threat of union influence.

The late 1880s saw a resurgence of profit-sharing and co-partnership in the form of share allocations with the introduction of eighty-eight schemes between 1889–92, compared with just forty in the previous fifteen years (Bristow, 1974: 274). As with the earlier phase of profit-sharing this revival could be directly associated with the effects of a buoyant economy on employment and consequent labour unrest (Church, 1971: 10), though Bristow also describes how companies would consider financial participation in order to increase productivity and help ‘overcome resistance’ to new processes of work (Bristow, 1974: p. 279). Discussing the renowned profit-sharing scheme introduced by the Taylor family in 1892 (which continued until 1966) Pollard and Turner (1976) ascribe three main motives to the use of share ownership. Two of these are based on the charitable exercise of moral philanthropy based upon the emotional satisfaction of giving, coupled with empathy towards recipients. The third is the more pragmatic and level-headed concern of its being ‘good for business’ through promoting ‘peace and goodwill’ and, in so doing, maintaining control over employees, which in the final analysis, is ‘at the core of every profit-sharing scheme’ (pp. 10–12). There were further surges of employer enthusiasm for profit-sharing in 1908–9 and in the period immediately prior to the First World War, again, in Church’s view, to be considered ‘as a method of combating labour unrest’ and having ‘little to do with philanthropic motive. It was a method of management’ (1971: 10).

The inter-war period saw a re-emergence of interest followed by unsteady expansion until 1929 and then slow decline throughout the depression years until the outbreak of war in 1939. In 1938, 399 establishments, covering approximately a quarter of a million participants, had schemes in operation, little more than ten years earlier.

Similar fluctuating patterns typify the post-war period, with a number of profit-sharing and share ownership schemes introduced in the early 1950s apparently being abandoned a few years later.1 A Ministry of Labour survey indicated that in 1954, 310 schemes were in operation in 297 companies, involving about 350,000 participants. No further surveys were conducted after this time, owing to the small number of schemes continuing to operate. The mean supplement to earnings provided by these schemes was estimated at 6.3 per cent, equivalent to about three weeks’ earnings, compared with an average profit-related bonus of 5.3 per cent between 1910 and 1938 (Hanson, 1965: 333). Following the mid-1950s decline, little further interest was shown in this approach to financial participation until the early 1970s (Brannen, 1983: 130), when first Conservative and, later, Liberal policies helped to stimulate the present renaissance.

The fluctuating history of employee profit-share arrangements suggests that such schemes have been implemented for two main purposes; as an act of faith by employers towards their employees, or as a means of securing employee compliance, often through inhibiting collective aspirations and activity. However, even during earlier peaks of employer interest, the number of schemes actually in operation at any one time was never more than a few hundred, confined largely to a limited range of industries such as gas, engineering and chemicals.2 Indeed, between 1865, the time of the first significant experiment, and the peak year of 1919 a total of only 635 plans had been implemented (Bristow, 1974: 262). A second important feature identified by the various Ministry of Labour reports was the high rate of discontinuation, with financial success probably being the key factor in determining scheme progress (Church, 1971: 13).

Nevertheless, other factors can account for the comparatively low rates of employer endorsement of profit-sharing and share ownership. In recent years, two reasons in particular may be advanced for low take-up: first, that the tax laws provided insufficient incentive for any but the most committed of employers to introduce profit-sharing; second, that political differences between the major parties offered insufficient legislative stability to induce companies to embark upon a possibly costly and probably temporary enterprise where tax incentives introduced by one government might be removed through a change in administration. This happened, for example, in 1974 when the incoming Labour government removed tax advantages from both executive share schemes and all-employee share-option schemes introduced by the Conservatives in the preceding two years.

By the mid-1980s this position had changed considerably, with legislation currently operating in the United Kingdom being described by one group of advocates as:

the finest employee share scheme legislation in the world … As a combination set [the main advantages] are unique … All together there are now no less than eight types of employee share schemes, all of them with some form of tax relief or advantage … [Copeman et al. 1984: 170]

Furthermore, the major political parties have all demonstrated some degree of commitment to employee share ownership: the 1978 Finance Act, which heralded the start of the new participative initiatives, was introduced by the Labour government, albeit with support from the Liberal Party and under pressure from them. Subsequent amendments and further legislation by the Conservative government have confirmed their support, whilst Liberals have traditionally been strongly in favour of profit-sharing, an enthusiasm subsequently shared by their SDP partners.3

These changes in political opinion, coupled with tax incentives, have induced significant growth in three major types of share ownership scheme. First there are schemes in which all eligible employees in an enterprise receive share allocations based on company profitability. Second, there are option schemes in which employees are invited to purchase shares in their company through a recognized savings scheme. When the savings period terminates, participating employees have the choice of taking up their shares or their savings plus interest earned during the period. The third type of scheme which receives government tax concession support is the so-called discretionary share option scheme, in which specified individuals or groups of employees are invited to purchase shares. Further details of the government- approved schemes may be found in Appendix 1.

In addition to these types of Inland Revenue-approved schemes, there is evidence of many cash-based profit-sharing schemes which do not involve employee participation or scheme ownership but are characterized by some form of bonus to employees based on profit or some other financial measure of performance at plant or company level.

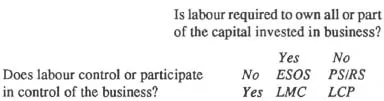

We are therefore faced by a potentially rich assortment of financial participation arrangements, particularly if the range is broadened to include co-operative and co-partnership arrangements for production. These diverse channels of financial involvement tend to be associated with a similarly broad spectrum of motive and objective. A valuable attempt to draw these strands together within an economic context has been made by James Meade (1986), who provided an analysis of the main types of labour involvement in profit-sharing and asset ownership. A dichotomy is drawn between the need for labour to be involved in ownership of capital assets and the extent to which, under any scheme, labour achieves partial or complete control over assets. Four main types of scheme are identified:

1 Employee share ownership schemes (ESOS), in which employees are allocated or are able to acquire shares in the capital of their employing organization.

2 Profit-sharing or revenue-sharing schemes (pS/RS), in which there is no necessary ownership of capital but employees are able to incorporate into their income from employment some share in profit or net revenue.

3 Labour-managed organizations or co-operatives (LMC), in which employees themselves provide the management of the enterprise or organization, and the equity is fully owned by employees.

4 Labour-capital partnerships (LCP), in which employees share in the firm’s revenue and exercise some role in controlling the firm’s operations, but without any requirement for ownership of capital.

Meade (1986:15) shows that these schemes differ in their approach to the key issues of ownership of assets and control, as follows:

Our main concern in this book is with the ESOS and PS/RS types of scheme, and the differences between them are clearly revealed. In neither case is there a necessary exercise of control over the business such as would exist in a fully fledged co-operative or partnership, so that the issues associated with these latter forms as a result of participative labour management do not arise. The ESOS and PS/RS approaches differ, however, in that only the former involves asset or equity ownership, and this is likely to carry different implications for the behavioural responses under different structural forms.

The economic motivation for the adoption of ESOS or PS/RS types of approach cannot lie in philosophies which seek to change the balance of social control over business, but rather with a more partial sharing by workers in the equity or the net proceeds of the business. The PS/RS schemes seek simply to relate pay to business performance by holding out to employees the prospect of sharing in profits which can be enhanced by greater work effort on their part. The ESOS type of approach goes further in providing for partial ownership of equity, thus committing employees to an investment in the affairs of their employer. A further understanding of the differences requires separate examination of these two varieties of scheme.

THE ECONOMICS OF FINANCIAL PARTICIPATION

Profit-sharing or revenue sharing

The economics of profit-sharing can be examined at either the micro- or the macro-economic level. The micro-economic concern is for the implications of profit-related remuneration in the individual enterprise. Two characteristics are important here. First, there is the potential incentive effect of a payment system which links workers’ productive performance and their remuneration. This link has much in common with output-related incentive payment systems, which seek to encourage higher productivity per employee, to the advantage of the employer through improved unit costs and of the worker through extra earnings. Similarly, profit-sharing may be seen as offering an incentive to employees to increase profitability, but operating as a group rather than an individual stimulus. A disadvantage of profit-sharing, like other forms of group incentive payment systems, is that it loses the directness of the effort-pay relation typical of most individual schemes; and, in large organizations particularly, the link between individual effort and profitability may be hard to discern, with adverse consequences for the intended productivity effect. Nevertheless, profit-sharing may be thought more effective than individual incentives in eroding the ‘them and us’ divide between owner and employees: the fact of employees sharing in the net proceeds of production could, in principle, increase commitment to enterprise goals and raise efficiency and profitability. Thus the ‘sharing’ aspect of profit-sharing schemes, even if not entirely successful in relating output performance to profitability, may indirectly raise productivity by an ‘X-efficiency’ effect (i.e. one which improves the performance of the enterprise not by improving internal resource allocation but by some more amorphous change which releases untapped productivity – for example, by greater employ...