I. Introduction

The United States faces large federal fiscal deficits in the immediate future, the next 10 years, and the longer term. Although the current and recent deficits are thought to be helping the economic recovery, the deficits in the medium term and long term are more troubling because of their potential impact on national saving, economic growth, and financial markets. Addressing these medium- and long-term challenges will likely require a combination of spending cuts and revenue increases. None of the relevant options (some of which will need to be implemented sooner or later) are particularly attractive from a political perspective.

In this chapter, we consider the fiscal outlook, how new taxes on carbon could not only help address the fiscal problem but also bring about benefits on economic and environmental grounds, and how these taxes compare with some other revenue options. Section II discusses issues related to the fiscal outlook. In section III, we highlight the revenue, efficiency, and equity effects of taxes on carbon emissions and/or a higher tax on gasoline. Section VI provides a brief comparison of a carbon tax to other revenue options – including a VAT and income tax expenditure reform. Section V offers a short conclusion.

II. Fiscal outlook and implications

This section summarizes the fiscal outlook, discusses why both revenue increases and spending cuts will need to be considered as part of the solution, and examines the long-term impact of tax-financed deficit reduction policies.

A. Fiscal outlook

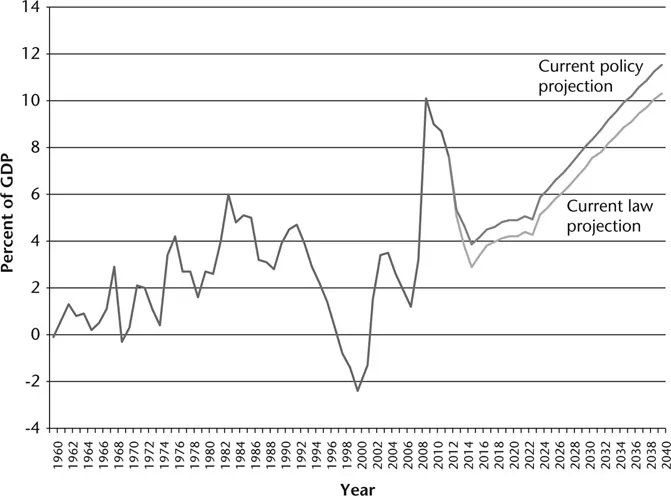

Figure 1.1 shows historical budget deficits and deficits projected under different future policy scenarios. Under the current-law baseline produced by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) assumptions the deficit falls from 5.3 percent of GDP in 2013 to 2.9 percent in 2018, before rising to 3.8 percent by 2023.

FIGURE 1.1 Deficits past and future, 1960–2040

TABLE 1.1 Major differences between current law and current policy baseline

| Policy option | Effect on the budget deficit in 2020 (percent of GDP) |

|

| Extend expiring tax provisions | 0.5 |

| Cancel sequester | 0.5 |

| Institute “doc fix” | 0.1 |

| Drawdown in defense spending | −0.3 |

| Remove disaster relief funding | −0.2 |

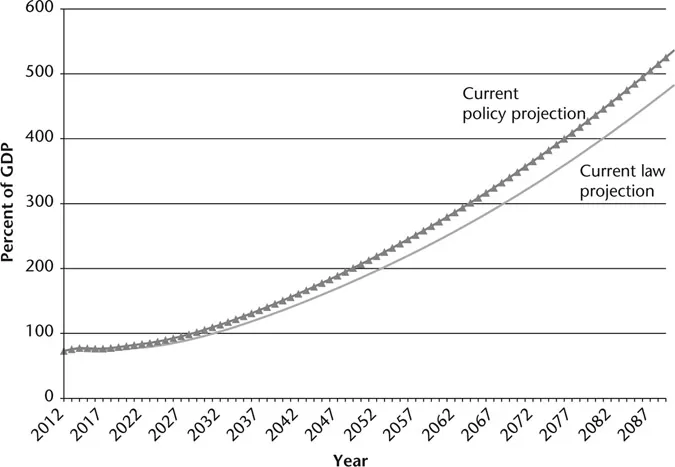

FIGURE 1.2 Alternative projections of the national debt, 2012–2090

Auerbach and Gale (2013a), however, show that under a current policy baseline (reflective of more realistic policies), the federal deficit under current policies will hover around 3.5 percent of GDP between 2015 and 2019, before rising to 4.5 percent by 2023 (Figure 1.1). The policy differences between current law and current policy baseline are shown in Table 1.1.

Moreover, after 2022, projected deficits are poised to rise further under both scenarios (Figure 1.1), reaching 10 percent of GDP by 2036 under the current policy baseline and continuing to rise thereafter.

As for the federal debt-to-GDP ratio, after averaging 37 percent of GDP in the 50 years prior to the Great Recession that started in 2007 and attaining a value of 36.3 percent of GDP in 2007, the ratio is now projected to pass its 1946 high of 108.6 percent in 2035 under current policy baseline (Figure 1.2). Unlike the aftermath of World War II, however, the debt-to-GDP ratio will continue to rise after surpassing the previous peak. Expenditures are expected to rise significantly as the aging of the populace and excess cost growth of health care cause Medicare and Medicaid outlays to grow rapidly. Current estimates place the fiscal gap – the immediate and permanent increase in taxes or reduction in spending that would keep the long-term debt-to-GDP ratio at its 2012 level – or 70.1 percent of GDP – at 4–7 percent of GDP through 2089 and 5–7 percent on a permanent basis (Auerbach and Gale 2013b).

In contrast to the U.S. projected fiscal trajectory, many organizations place the desired debt/GDP ratio between 40 percent and 60 percent.1 It is not entirely clear how an optimal debt/GDP ratio can be derived from theoretical first principles. What is clear, however, is the current trajectory for U.S. debt is not sustainable.

Although delayed implementation of deficit-reducing policies may be preferable given the current state of the economy, the longer it takes to put in place deficit-reducing policies, the larger will be the required spending cuts or tax increases in order to address the long-term fiscal gap. For example, if the adjustments are delayed until 2018, when the CBO projects the economy will reach potential GDP, the fiscal gap increases by up to 0.3 percentage points of GDP.

Budget projections (especially for the long term) embody considerable uncertainty, and deficit projections are particularly uncertain as relatively small percentage changes in outlays and revenues can lead to relatively large percentage changes in deficits. In the current environment, economic projections also may be more uncertain than usual, given uncertainty about the effects of the recent recession on the long-term growth rate. The other major uncertainty is the rate of growth of health care spending, which can have enormous impacts on the projected budget outlook. Despite this uncertainty, it is hard to paint an optimistic picture of the fiscal outlook. Indeed, the projections above are based on a series of economic and political assumptions that could be viewed as optimistic.

B. The need for spending cuts and revenue increases

Since projected spending is slated to rise faster than GDP for the indefinite future, it is clear that spending cuts must be part of the solution, in particular for government health care programs, which have been rising as a share of GDP for several decades and are projected to continue to rise.

There are several reasons to consider tax increases (beyond those already included in the January 2013 budget deal), however, as well as spending cuts, as part of the fiscal solution. First, the sheer magnitude of the fiscal gap suggests that a spending-only solution would need to impose very substantial reductions on spending that might not be seen as equitable. At 5–7 percent of GDP, the fiscal gap is several times larger than the savings that were generated in budget deals in the past. The 1983 Social Security Reform reduced deficits by about 1 percent of GDP in the four years after passage while the 1990 and 1993 budget deals reduced deficits by about 1.4 percent of GDP and 1.2 percent of GDP, respectively, over the 5 years after passage.2 The recently enacted tax bill only raised 0.3 percent of GDP in revenue over the next decade. In addition, Americans seem particularly reluctant to cut government spending on Social Security and Medicare, two of the key drivers of long-term spending, than on other forms of spending. For instance, a 2011 Gallup poll showed that over 60 percent of Americans were unwilling to cut Social Security and/or Medicare, and this was true across the political spectrum.

Second, as a political equilibrium, it seems likely that a sustainable budget deal would draw from both sides of the ledger. Indeed, in the past, major deals have included both tax increases and spending cuts. With the 1983 Social Security reforms, the 1990 bipartisan budget deal, and 1993 budget deals, Congress both slashed spending and raised taxes. For example, in the 1990 budget deal, 49 percent of the reductions came from higher tax receipts, 34 percent from reduced defense spending, and 17 percent from other cuts in spending (Steuerle 2004).

Third, as a matter of equity, the only way that high-income households will share significantly in the burden of fixing the deficit is through revenue increases since spending cuts typically do not have a large impact on high-income households.

Fourth, spending appears to be controlled more effectively by requiring that it be paid for with current taxes, rather than allowing deficits to grow. In contrast, the “starve the beast” hypothesis argues that keeping revenues down is an effective approach to curtailing spending. However, the hypothesis does not appear to be consistent with recent experience.3 And evidence in Romer and Romer (2009), for example, suggests that tax cuts designed to spur long-run growth do not in fact lead to lower government spending; if anything, they find that tax cuts lead to higher spending. This finding is consistent with Gale and Orszag (2004a), who argue that the experience of the last 30 years is more consistent with a “coordinated fiscal discipline” view, in which tax cuts were coupled with increased spending (as in the 1980s and 2000s) and tax increases were coupled with contemporaneous spending reductions (as in the 1990s).

C. Long-term growth effects of tax-financed deficit reductions

An increase in taxes will not necessarily slow long-term economic growth. Tax changes have two broad sets of long-term effects on the economy.4 The first set operates through direct changes in relative prices, incentives, and after-tax income. These changes affect the degree to which households are willing to work, save, invest in education and training, and so on, and to which firms invest and hire; these effects are known as income and substitution effects. Thus, for example, increases in marginal tax rates, holding other factors constant, can reduce the size of the economy and reduce economic growth.

However, other factors are not constant. The second broad effect is on national saving. A reduction in the deficit tends to raise public saving, which typically results in higher national saving (national saving is the sum of household, corporate, and government saving). This effect is often ignored in discussions of tax policy and economic growth, but it can be quite important.

Containing deficits matters for several reasons.

Sustained deficits may enhance the risk of a financial crisis. Even in the absence of precipitating a financial crisis, however, sustained deficits have deleterious long-term effects, as they translate into lower national savings, higher interest rates, and increased indebtedness to foreign investors, all of which reduce future national income. In addition to the growth impacts, sustained deficits may impose unfair burdens on future generations and may constrain U.S. foreign policy or defense positions, especially as they relate to creditor nations.

Gale and Orszag (2004b) estimate that a 1 percent of GDP increase in the deficit will raise interest rates by 25 to 35 basis points in the United States and reduce national saving by 0.5 to 0.8 percentage points. Engen and Hubbard (2004) obtain similar results with respect to interest rates. Thus, relative to a balanced budget, this study suggests a deficit equal to 6 percent of GDP would raise interest rates by at least 150 basis points and reduce the national s...