![]()

| Part I |

| Globalization in three dimensions |

![]()

| 1 | Globalization and place – the death of geography? |

● Globalization and the death of geography

● Protest against globalization – a global justice movement?

● Competing discourses of globalization

● Defining globalization

● Geography and the study of globalization

● New globalizing spaces?

● This book – 16 geographical questions about globalization

Globalization and the death of geography

As Warwick was sprinting to his inaugural lecture in 2012, entitled Globalization and Geography in Crisis, the Deputy Vice Chancellor of the university saw him racing to the theatre with an inflatable globe in his hand. The Deputy Vice Chancellor said, “you’re right, it is a small world!” We live, if the hyperbole is to be believed, in a ‘global village’, or at least some of us do. The term that is most commonly used to refer to this apparent shrinking is ‘globalization’.

In January 2009, Warwick sat in Chonchi on the island of Chiloe, a small isolated rural locality in the south of Chile, watching BBC Mundo whilst simultaneously listening to the internet broadcast on CNN of Barack Obama’s inauguration. This was the installation of the first black President of the USA who had dual African and European heritage and was born in Polynesia; he couldn’t help but feel in awe of the reach and intricate complexity of globalization. John felt the same in September 2010 in Cape Town, when he learned of the Canterbury earthquake in New Zealand, being able to watch reports on BBC television and listen to internet radio from Christchurch talkback stations. He was actually better informed about the damage than some relatives without electricity in Christchurch. These moments of a globalized imagination are surely becoming more and more common for many people. Many reading this book now would have personal examples with accompanying mental images that speak of the vastly interconnected and complex world in which we live (see Plate 1.1).

We live in a world that our grandparents, and perhaps even our parents, could never have imagined in their wildest dreams. For most, what has changed most dramatically in the world has been technology: cell phones, computers, digital cameras and the like. Yet perhaps equally startling have been changes in the way the world is structured and connected. For example, it is remarkable to note how communication has globalized over the last 25 years. This introductory chapter was written in part whilst sitting in the Duke Humphrey’s library which is the oldest part (approaching 500 years) of the Bodleian Library at Oxford University – the oldest library in Europe and undisputedly a centre of learning for many centuries. When we compare the fixed nature of the books and artefacts in this library to the accessibility that is granted through search engines such as Google, online encyclopaedias such as Wikipedia and video-sharing technologies such as YouTube, we can only be astounded by how things have changed.

As such, globalization is tied up with the twentieth-century revolution in transport and communications technology that has captured the popular imagination. It is possible today, for example, for a member of the general public to circumnavigate the world in just over a day on commercial airlines. Sixty years ago, the air journey from England to Australia took about a week. In 1870, it would take 70 days for surface mail to travel from London to New Zealand. With the advent of the telephone and faxes, e-mail, and more recently internet-based social media such as Twitter, communication across the world, and even beyond, can be instant.

Increasingly used to rationalize a wide range of economic and political policies, and to explain a plethora of cultural, social and economic processes and outcomes, the concept of ‘globalization’ has assumed enormous power. Despite this, it is not always well defined or critically appraised in either popular or even academic usage. A common image of globalization is one of a process that unfolds like a blanket across the globe, homogenizing the world’s economies, societies and cultures as it falls. Everywhere becomes the same, boundaries don’t matter and distance disappears, so the argument goes. If communication is now instant, if where we live no longer matters, and if things are the same wherever we are, does globalization spell the end of geography?

Plate 1.1 Dubai Mall – the epitome of high neoliberal globalization?

Shopping malls are ubiquitous. Wherever they are in the world, they often contain similar chains of shops, they sell global brands and they are arguably the most common sites where people from all over the world connect with the global economy.

Source: Photo by authors

The end of geography?

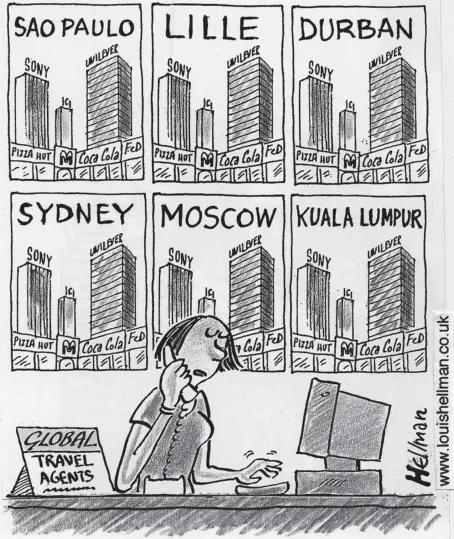

People have been predicting the death of geography for nearly four decades on the basis of the trends discussed above. Toffler (1970) led this perspective in Future Shock, arguing that the evolution of transport and communications technologies and the intensified flows of people that have resulted imply that the principal source of diversity is no longer space. Twenty years ago, the subtitle of O’Brien’s Global Financial Integration proclaimed ‘the end of geography’ – a situation involving ‘a state of economic development where geographical location no longer matters’ (O’Brien, 1992, p. 1) (see Cartoon 1.1) (see Dymski, 2009 for a strong rebuttal of this argument).

Cartoon 1.1 Homogenized destinations

Source: Louis Hellman

There can be little doubt that, relative to the past, people and processes in ‘far-off’ places can have instant ‘local’ impacts. Geographers and other social scientists have used a number of other terms for this process including ‘annihilation of space by time’, ‘time–space convergence’ and ‘time–space compression’ (see Map 1.1) (Harvey, 1989, 2007). Economic contagion became a new buzzword in financial sectors, following the Asian ‘crisis’ of 1997 which quickly spread around the Pacific Asia region from Thailand to South Korea and on to Japan. This term was used again to describe the alarming velocity at which the credit crunch in the USA in 2007, and the eventual Global Financial Crisis of 2008/9 which it precipitated, raced across the globe – the ramifications of the collapse had a rapid and tangible impact on economies all across the world to varying degrees.

But this ‘shrinking’ is by no means just economic in nature – it appears to be permeating all spheres of human activity and experience. Twenty-four-hour news providers and other broadcasters, such as CNN, Al Jazeera and the BBC, report unfolding political, social and cultural events – such as the death of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela in 2013, the London Olympics opening ceremony in 2012 or the devastating Japanese tsunami of 2011 – in real time to people’s homes and offices across the planet. Also the news providers increasingly rely on text and footage in the reporting of such phenomena from participants on the ground during such events, as was witnessed with the capture and gruesome killing of former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi in 2011.

In the political and diplomatic sphere the impact of WikiLeaks, the website established by Julian Assange in 2006 to broadcast whistle-blower-generated leaks of sensitive government communications across the world, will resonate for many years to come and continues to reveal state secrets and classified interactions. Depending on which view one takes, this example of the globalization in the political sphere can be seen as highly liberating (some credit the spark for the Arab Spring as the revelation of corrupt activities through WikiLeaks, for example) or as tantamount to informational terrorism that has cost lives, as some members of the US government have argued in making the case for the arrest and prosecution of Assange and the whistle-blower Edward Snowden in 2013.

In the environmental sphere, carbon dioxide emissions in the USA or China have a direct impact on small island states as sea level rises and cyclone events become more common in localities such as Grenada in the Caribbean or Niue in the Pacific. Feasibly, then, we could talk of increased cultural, social, environmental and political contagion given the new fluidity of global flows. It is clear that the way that many of us experience the world is shifting in sometimes dizzying ways and that a revolution in technologies of interaction has played a central role in this (see Box 1.1 and Plate 1.2).

The core aim of this book is to illustrate that as the processes of globalization fundamentally alter the way people, commodities and information flow and interact, this creates new and complex geographies. Popular notions of what globalization is often misunderstand what geography is, both as an entity and an academic discipline, and fail to appreciate how contemporary geographers define central components of their analysis such as space, place, scale and location. There are two notes of caution that need to be sounded about the ‘shrinking world’ concept immediately. First, the relative distance between some places and people has become greater. For example, the income gap between the poorest and richest countries and peoples has increased over the past 50 years (Potter et al., 2008). Those who are hooked up to the internet may enjoy rapid communications with distant friends who can appear to be just around the corner, but the majority who do not have access to such technologies have become relatively more isolated. The fact that ‘shrinking’ technology can drive places apart is illustrated in Map 1.1, which shows the simultaneous time–space convergence and divergence of the world measured in terms of the cost of a minute-long phone call from the USA in 2000. In short, rather than smothering the Earth like a blanket, globalization has cast a net across it, and this has increased spatial differentiation accordingly.

Box 1.1

Transportation and communication milestones