![]()

Chapter 1

Investigating objects

Theories and approaches

1.1 Definition of objects/artefacts

Strictly, every piece of evidence of early human activity should be categorized as an artefact.

(Biek 1969: 567)

The word ‘artefact’ is derived from the Latin terms ars or artis, meaning skill in joining, and factum meaning deed, also facere meaning to make or do (Prown 1993: 2). Thus an artefact can be considered to mean any physical entity that is formed by human beings; from a nail to the building it is in. The term ‘object’ is also widely used to refer to any physical entity created by human beings. It depends on the age, origin and academic orientation of the author as to which term is used. For the purpose of this book, the terms ‘artefact’ and ‘object’ are used interchangeably, and whilst references are made to buildings and paintings, the focus is on the types of archaeological and historic objects found in museum displays.

Artefacts are one of the principal methods by which we communicate and mediate with the world around us, Schiffer (1999) suggesting that the constant use of large numbers of artefacts is the principal difference between human beings and animals:

… never during a person’s lifetime are they not being intimate with artefacts.

(Schiffer 1999: 3)

Human beings are sociable animals who are invariably grouped into societies. These share non-biological aspects such as ‘knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom and many other capabilities and habits’ which we can describe as culture (Tylor 1871, in Renfrew and Bahn 1991: 9), the physical remains of which are referred to as material culture. Studying the artefacts of a material culture can inform us about the individuals and societies that created and used them; however,

… the relationship between material culture and the people who produce it is a complex one.

(Hodder 1991: 2)

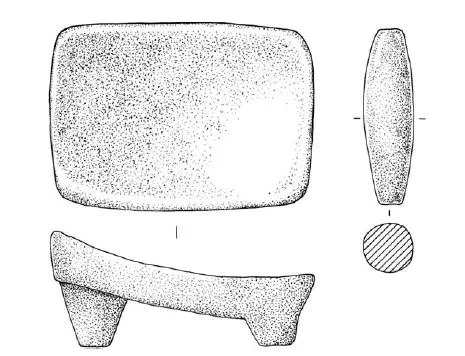

Figure 1.1 Metate and mano: Mesoamerican maize grinder. (Drawn by Yvonne Beadnell)

1.2 Objects in the present

Modern anthropological studies have provided models for the way in which human societies make and use objects. They usually consider artefacts as part of economic systems, belief systems (religion), wealth display and social ranking (Ember and Ember 1996). However, fieldwork tends to provide examples of object production and the economic, practical and cultural constraints of object use. A good example is provided by the work of Horsfall, Hayden and others in studying the use of grinding stones in contemporary Mayan peoples of Central America (Hayden 1987; Horsfall 1987).

The staple food of the peoples of the Mayan Highlands of Central America is maize flour, ground wet on grindstones, present in most houses of traditional communities such as the village of San Mateo. The lower grindstone (metate) is rectangular in shape, often with three small projections or feet at its base (see Figure 1.1). The upper surface is inclined between four and forty degrees, though most usually ten to twenty degrees, up from the horizontal. There is a slight raised rim around the edge of some stones. The upper grindstone (mano) is roughly cylindrical, of slightly larger diameter in the centre than at the edges; in many cases the mano is slightly wider than the metate (see Figure 1.1). Many features relating to the material selection, production and use of these objects could be noted:

• Though the local geology is limestone, 100 of the 120 grindstones were made of vesicular basalt. This imported stone is particularly efficient at grinding maize, the vesicular structure giving an efficient cutting action. It is a hard rock and so does not wear away quickly. The basalt is preferable to other hard rocks such as quartzite or conglomerate, because they gradually break up, producing grit in the flour. Basalt wears away very slowly as a fine powder, thus no grit in the flour. The preference for hard igneous rocks for grindstones is seen throughout Central America, with rocks such as andesite, granites and basalts being traded up to 250 miles from source to point of use.

• The grindstones cost approximately 3.6 per cent of the median annual income; the same level of investment as a small car in Western European societies. Consequently similar levels of concern over the cost-effectiveness, working life, etc., may be expected. There are black and white varieties of basalt grindstone: white is softer, lasting about 15 years; the black is harder and longer-lasting, consequently it is more expensive.

• The design of the grinding stone is very practical and highly evolved for its function. The three projections, legs on the base of the metate, allow it to be used on any surface; flat bases or four legs would wobble on all but flat surfaces. The angled upper face allows the most efficient grinding action: if flat, it is difficult or energy-sapping to pull the stone back from its farthest extent. If it slopes too steeply, the user crushes the maize rather than grinding it. The ten-to twentydegree slope is the most efficient. The raised lip at the edge prevents material being spilt out of the side. The mano is wider than the metate so that people do not trap their fingers between the two.

• Smaller grindstones are generally used for herbs or coffee-grinding, though some families use the same one for grinding all foods, and some use old maize grinding stones for grinding other materials. Larger ones could be used for washing clothes, and were often found near water sources. Thus the size gives some indication of use, though reuse of old stones and the variations in the type of use lead to a natural variability which partially obscures the size/use relationship.

• Grinding stones were present in all but a couple of houses in the village: those households without one were usually single adults who returned to their parents’ house to eat.

• If houses had several grinding stones, they either had different uses, or there were several women in the household, or stones were being stored. Grindstones, unless stored, were present in the kitchen/living rooms, the working areas of the house.

• Earlier pre-conquest household grinding stones were often simpler shapes and softer rocks. The tripod, inclined rectangular form was more often seen for ceremonial uses. However, the conquest brought the use of iron/steel, which allowed stonetobequarried andshapedmoreeasily. Consequentlythemoreefficient andeffectiveshapecouldbemademorecheaplyandbecamemorewidely available.

• The level of use of stone grindstones in San Mateo was high, as was the level of use of traditional herbs, traditional religious practices and communal activities. In a similar village, Aguacatenango in Mexico, there was far less use of stone grindstones; metal grinding mills, some electrically driven, were more popular, though they did not last as long as the stone grindstones. There was little use of traditional herbs; traditional religions had been forsaken for Christian, principally Catholic, beliefs; and there were far fewer communal activities. The stone grindstones appear to be part of a larger cultural tradition. A newer series of cultural objects and beliefs has now developed at Aguacatenango: the older material culture and traditions remain in San Mateo.

The form of the grinding stones was primarily derived from function, though a historical/cultural tradition favouring that design was evident. This led Horsfall (1987: 370), to comment: ‘Social tradition too seems to have an influence on form within the limits allowed by functional and technological constraints.’

This information was obtained through direct observation of the use of the object, its manufacture, the selection of the raw materials and its reuse. It was seen in its context – its place of use, surrounded by associated items as part of a complete cultural assemblage. It was possible to talk to the makers and users of the object to discover their reasons for making, shaping and using the object as they did. Large numbers of the object were available to study, so that ‘normal’ manufacture and use was distinguishable from the unusual. Variations in form, material, use, etc., could be correlated with subtle cultural and social differences. Many of these types of evidence are not available when studying objects of the past, where only fragments survive and there are no manufacturers or users to reveal the reasons for the object’s use, manufacture or reuse.

1.3 Objects of the past

The simplest objects are natural materials such as animal bones, which bear the cuts from flint blades used for removing flesh or skin from the animal. The largest and most complex are buildings such as a cathedral, or machines such as an aircraft carrier. Objects form the material culture; the physical remains by which almost all ancient societies are defined, though it is not always an easy matter to identify an object. Stones with smoothed or worn faces can be formed in a stream, on the seashore or beneath a glacier; however, other examples are man-made and form some of the simplest objects studied by archaeologists. Examples of such stones are hone stones used for sharpening metal blades, a number of which were recovered from the thirteenth-century medieval castle of Dryslwyn in west Wales, (see Figure 1.2). A number of factors went into the identification of these particular stones as hone stones and not natural fragments of rock. These included:

• The size and shape to function efficiently; large enough to be useful for sharpening a blade, small enough and conveniently shaped to hold.

• The material of the stone. Soft or glassy stone would not sharpen a blade, only hard vesicular stones such as sandstones are effective for sharpening.

• The smoothing or wear which is characteristic of blade sharpening. Microscopic traces of metal may be found in...