![]()

1

A Great Commotion: The Experience of the New Madrid Earthquakes

EARTHQUAKE

We have postponed a number of articles prepared for this evening’s paper, to make room for the following very interesting communication from an intelligent friend at New Orleans.

It is we presume the most particular and satisfactory account of the earthquakes on the Mississippi which has yet been published: And Mr. Pierce being an ear and eye witness to the scenes he describes, the authenticity of his narrative cannot be doubted.1

Hampshire Federalist, Springfield, Massachusetts, February 11, [1812]

. . .

By February 1812, many people in North America were unsettlingly aware of a series of disruptions that had occurred somewhere along the edge of the growing American nation. From the upper Missouri River to Upper Canada, from Georgia to Connecticut, many people over the previous three months had felt rocking and shaking, heard strange sounds, witnessed the movement of objects and the alarm of animals and birds, or felt disturbing symptoms in their own bodies. These puzzling and sometimes frightening events were big news in 1812.

In widely circulated journals and idiosyncratic local papers, from substantial communities and tiny settlements, people shared their impressions and sought others’ knowledge about these natural disturbances. Some reports were just a few snippets of description—questions, really: had anyone else felt the shakes? heard all the noise?—while other accounts went on for long passages comparing many neighbors’ experiences or offering parallels from historical tremors. Surveying the abundant printed evidence of the New Madrid earthquakes is like looking through the pieces of a massive puzzle spilled from a box onto a table top. The brightly colored pieces are hard to sort for order and connection.

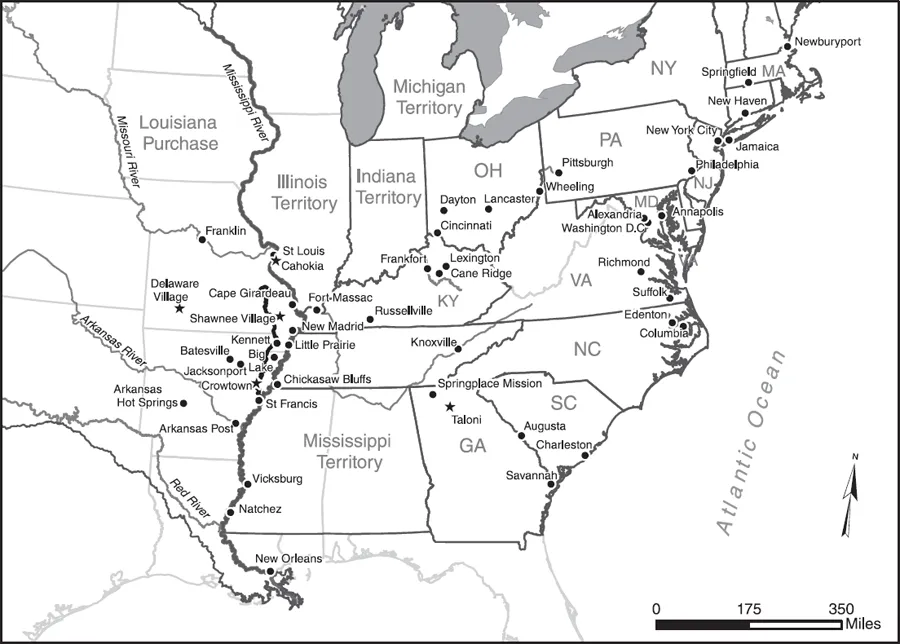

FIG. 1.1. United States, 1811–12, at the time of the New Madrid earthquakes. (Geographer: Bill Keegan)

One particular New Madrid account, published by the Hampshire Federalist on 11 February 1812, brings the larger pattern into clear focus. Written by river traveler William Leigh Pierce, this “interesting communication” was among the longest of the immediate eyewitness reports; it appeared in scores of different newspapers, and it addressed events and fears that appear common to many other accounts. His narrative thus provides a guide for modern people interested in the quakes just as it did for readers of many newspapers in 1812. To follow Pierce in his downriver journey is to read how the New Madrid earthquakes would enter American experience.

Pierce’s account held great interest in 1812, and it remains fascinating in the early twenty-first century. In the 1960s and ’70s, during the beginnings of seismological reassessment of the New Madrid earthquakes, researchers lamented their reliance upon “often exaggerated, inaccurate, and sometimes fanciful narratives prepared at the time.”2 More recently, researchers have returned to reassess accounts like his, to piece together a modern scientific explanation for the events he chronicles. Pierce’s narrative thus offers a window not simply into the experience of the earthquakes when they happened, but into how successive generations of researchers have come to comprehend them.

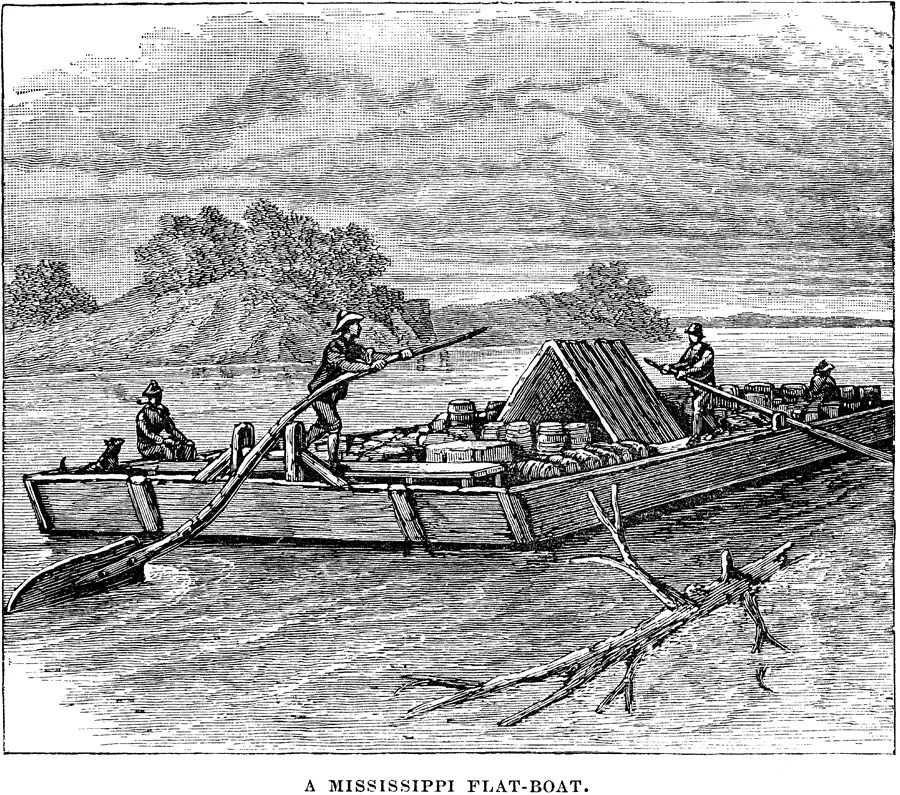

FIG. 1.2. “A Mississippi flat-boat.” William Leigh Pierce was traveling the Mississippi in a boat much like this when the first shocks of the New Madrid earthquakes hit in December 1811. Earthquakes that disrupted American access to the commercial artery of the Mississippi were of national interest, as the many reprintings of Pierce’s earthquake account make clear. (Samuel Adams Drake, The Making of the Great West, 1512–1883 (1891), 164, image 2003-0517, courtesy of the State Historical Society of Missouri–Columbia)

Public interest in New Madrid accounts like Pierce’s reveals the tensions of 1812, when new commercial networks were spreading further across North America, explorers sought to survey western territories only recently claimed by the United States, and war over commerce, territory, and culture was brewing between beleaguered Native nations and a young American republic and between the United States and Britain. As we follow Pierce on his journey downriver, we can discern with vivid clarity the scenes of destruction he describes, the lens of natural inquiry through which he registers and describes the devastation, and his assessment of its social and political consequences in the national and environmental context of early nineteenth-century America. Reading Pierce, we can see how knowledge was made in early America.

William Leigh Pierce and His Account of the Earthquakes

At the end of 1811, William Leigh Pierce was part of a convoy of shallow-bottomed boats taking goods from the Ohio River down the Mississippi to the international trading port of New Orleans. Pierce was part of the United States’ second national generation. His mother had been a Carolina planter and his father (also a writer and also named William Leigh Pierce) fought in the American Revolution and was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention that had formed the framework for the country.3

On the night the first of the “hard shocks” hit, Pierce’s convoy happened to be lying anchored off the small community of Big Prairie, a little below the trading town of New Madrid, Missouri, in the Mississippi River below the confluence of the Ohio and Missouri. He mailed off a long narrative of his journey once he reached New Orleans. His account thus traced the earthquakes’ effects along the middle and lower Mississippi. The Hampshire Federalist’s staff felt evident relish at being able to relay Pierce’s report of what he saw and heard. It promised to be a good one.

The reading public at the time evidently agreed: Pierce’s account of the earthquakes—which eventually included several follow-up reports as well—was excerpted, quoted, and reprinted throughout the American popular press in 1812. Such multiple and overlapping publishing was typical of the conversations about the New Madrid earthquakes: accounts frequently appeared in multiple forms, quoted and re-cited, their information hashed through repeatedly in various abridgements or compilations. Newspapers such as the Hampshire Federalist were where people got news and argued opinions in early America: almost every town had at least one. They were stridently partisan (just like the Federalist), and they were passed along and shared long after their particular issue date. More literary readers could also have encountered Pierce’s report in several books and pamphlets on the recent quakes, as well as in his own narrative poem, The Year, published in 1814 to commemorate the war and earthquakes of 1812.* Collections of earthquake accounts were soon rushed into wider circulation: Robert Smith, a Philadelphia printer, published a pamphlet compiling reports on the quakes in 1812, as did an anonymous printer in Newburyport, Massachusetts.4

Accounts of the New Madrid earthquakes were generally written as letters, and their form bears witness to the close connections between letter writing and newspaper reporting in the early nineteenth century. Like reports of new settlement sites, relations with Native groups, or recent epidemics, many accounts of the quakes began as letters from one individual to another person or family, with the explicit understanding that they were for common consumption and might be forwarded to a local paper. Particularly vivid recountings of the New Madrid earthquakes were reprinted several times over, appearing often in newspapers located successively further East.5,†

Little can be gleaned from many authors, who followed nineteenth-century conventions of letter writing and publication in signing many reports only with an initial or pseudonym—“J.S.” or “Dr. M.” or “A Concerned Resident.” Such conventions may have allowed for the participation of female writers at the time, but hide them now. Women also may have sent their own accounts through male family members, as was common practice.6

Of course, not all of the discussion in the early nineteenth century about New Madrid—or anything else—was written down. People discussed the New Madrid earthquakes in trading houses, around campfires, in Indian lodges, in sewing parlors, and in big-city coffeehouses. At two centuries’ distance, what remains are the parts that got written down. Only a few snatches of conversation and discussion remain caught in diaries or letters like tufts of fur caught on barbed wire, small but telling clues to a larger whole.7 Through this written record emerges a story of the gradual creation of public knowledge and public memory about these earthquakes—knowledge and memory that would all but disappear by the end of the nineteenth century, only to re-emerge through close consideration of accounts like Pierce’s as the twentieth century gave way to the twenty-first.

TO THE EDITOR OF THE NEW-YORK EVENING POST.

BIG PRAIRIE, (on the Mississippi, 761 miles from New Orleans,) Dec. 25th, 1811.

DEAR SIR,

Desirous of offering the most correct information to society at large, and of contributing in some degree to the speculations of the philosopher, I am induced to give publicity to a few remarks concerning a Phenomenon of the most alarming nature. Through you, therefore, I take the liberty of addressing the world, and describing, as far as the inadequacy of my means at present will permit, the most prominent and interesting features of the events, which have recently occurred upon this portion of our Western Waters.

To begin his account, Pierce situated himself in terms everyone of his day would understand: 761 miles north of New Orleans, a vast distance by land or upstream, but a distance traversable in less than three weeks downstream. He had entered the Mississippi from the Ohio, a central river route of the eastern American country; to his north was St. Louis, a small but important and growing trading town that anchored the confluence of the Missouri and the Mississippi. He was on the “Western Waters,” that is, on the flowing network of rivers that Americans envisioned as soon connecting communities and settlements of east and west.8

Pierce also situated himself intellectually, as part of a community of observers responsible for contributing usefully both to “society at large” and to “the speculations of the philosopher.” Far from implying some esoteric or removed group, in Pierce’s intellectual world this was a typically ornate way of talking about the widespread process of figuring out why the world worked as it did. This was the job not of remote, long-bearded elites in a high tower, but of men of education and substance casting keen eyes upon the world—among whom Pierce clearly included himself.

Proceeding on a tour from Pittsburg to New Orleans, I entered the Mississippi where it receives the waters of the Ohio, on Friday, the 13th day of this month, and on the 15th, in the evening, landed on the left bank of this river about 116 miles from the mouth of the Ohio. The night was extremely dark and cloudy; not a star appeared in the Heavens and there was every indication of a severe rain—for the three last days indeed, the sky had been continually overcast, and the weather unusually thick and hazy.

Unusual weather was no small side comment. In the natural philosophy of Pierce’s day, processes of earth and sky were closely related, and many theorists posited that changes in weather might cause or at least might indicate earthquakes. Such clues would prove important to those attempting to tease out the web of connections that bound and made sense of such an overwhelming phenomenon of the earth.

A trip from Pittsburgh to New Orleans, similarly, was no small undertaking: it meant venturing across what American imagination viewed as the heart of the continent, to the confluence region where the Ohio, the Mississippi, and the vast Missouri Rivers all came together in an area of longstanding commercial and cultural importance. Such a trip encompassed the middle Mississippi Valley—the area roughly from the coming together of those three rivers to the mouth of the Arkansas, pulling together the modern American states of Missouri and Arkansas, western Tennessee, Kentucky, and Mississippi, and southern Illinois.9

The region where Pierce anchored during that first “hard shock” was at the northern end of what is known as the Mississippi Delta or the Mississippi embayment: the deep, gradually broadening and widening, roughly conical trough formed by the gradual deposition of organic sediment by the ancient grandparent of the Mississippi River. Over vast time, this long-flowing ancient river formed all of the Mississippi Delta, from just below the mouth of the Ohio down to the Gulf of Mexico. The rich sediment deposited by the ancient Mississippi and lack of underlying rock structure endow the Mississippi floodplains with their astonishing fertility: corn and cotton grow extremely well in soils hundreds of meters thick. The loosely deposited soil (in geological terms, the unconsolidated sediment) also endowed the region with the propensity to shake astoundingly and alarmingly when subjected to seismic waves.‡ The entire Mississippi basin is the large-scale equivalent of fill land, much like the portions of the San Francisco Marina neighborhood that turned to liquefied morass during the 1989 Loma Prieta quake. In geological terms, the structure and history of the Mississippi embayment would later become part of what was under debate as researchers struggled to understand the events that Pierce was about to relate. In political and cultural terms, the Mississippi embayment was an area of conflict and struggle in December 1811.10

The west bank of the Mississippi had just become legally American a few short years before, with the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. Beginning in the late 1600s, the French had worked with Quapaws along the Arkansas River and with Osages on the branches of the Missouri to negotiate trade, mining, and small-scale French settlements. After the multinational conflict known in Europe as the Seven Years’ War and in North America as the French and Indian War, France ceded international control to Spain in 1763. Spanish control was even weaker than France’s had been, and Spain’s diplomacy less adept at the familial metaphors and elaborate exchanges of mutual obligation by which Native groups like the Quapaws and Osages were accustomed to maintain peace or wage war. In 1800, because of European financial and political pressure, Spain ceded Louisiana (much of the area between the Mississippi and the Rocky Mountains) to the French under secret agreement. Soon thereafter, American negotiators found themselves somewhat surprised to be negotiating with a weary Napoleon a purchase price for the mid-American continent between the Mississippi and the “Stony Mountains.”11

The Louisiana Purchase is justly famous in American history, but it was somewhat puzzling to leaders at the time. President Thomas Jefferson fretted that his purchase was expedient but constitutionally unsanctioned, and no one had a very precise idea of what territory had in fact changed hands. But what was clear to most people—Indian, French, American, and various others—was that the middle Mississippi, the area that opened out onto the Purchase, was a crucial area for shaping the diplomacy, trade, and politics of future settlement.§,12

An important concern for Americans, both in the Louisiana Purchase and in later conflicts with European powers that resulted in the War of 1812, was keeping Mississippi commerce flowing. One of the first acts of American possession of Louisiana was to lift trade limits imposed by the Spanish. ...