![]()

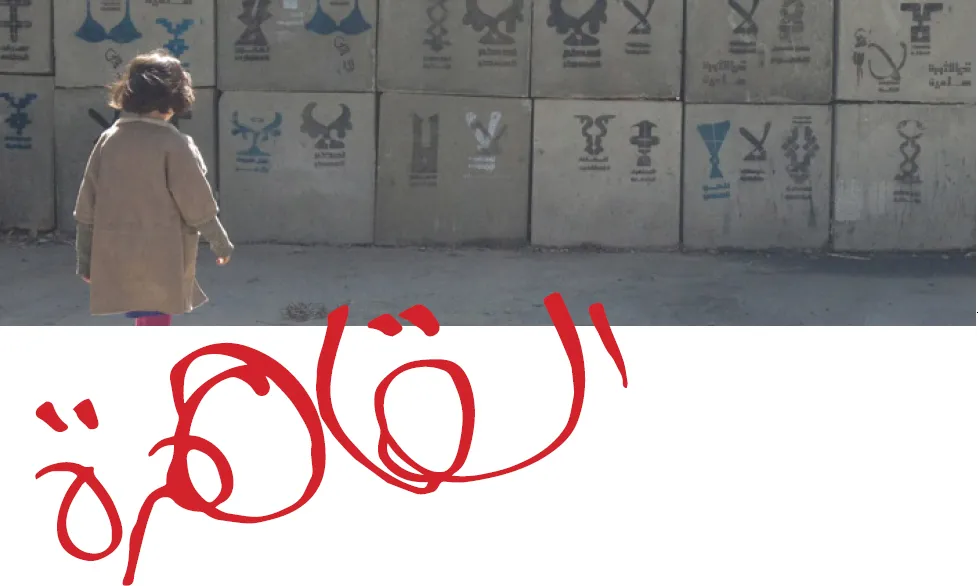

Cairo:

You Can Crush the Flowers

I cannot paint in Cairo. No one wants to hear about the Revolution any more. Supporters of the old regime of the former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak and those who continue to idolise the military still refer to January 25th as an external intervention by enemies of the state, a cloud that has since passed. To the millions who were in Tahrir Square, however, the Revolution is an aborted dream. The government and its operators have done their best systematically to erase all evidence of our brief moments of freedom. As artists we cannot practise in the street because we channel human emotions, and the general atmosphere in Egypt is one of discomfort.

No one wants to talk about the Revolution. So we stay silent. Outspoken activists who were once symbols of the Revolution are either dead, imprisoned or in exile. So we stay silent. The mouths that once sang and chanted for freedom have been kicked into silence by military boots. So we stay silent. Cairo is an aggressive megalopolis, a city that eats its children. It is loud, dusty and polluted by day, tense and anxious by night.

The city kills the aspirations of its millions of creative souls. Nowadays in Cairo we wake up each day to the news of the death of a promising young talent. Cause of death: unfulfilled dreams.

I stopped painting on the streets of Cairo in 2013. For two years, with the city as my canvas, I had been painting for the Revolution on the walls of Cairo. In November 2011, after documenting the Revolution for nine months as an online archivist, I had had enough. I saw a video of people being shot, their corpses piled up like rubbish on the street. A few months earlier, in January 2011, my artwork ‘A Thousand Times NO’ was uninstalled at the Haus der Kunst in Munich. In that project I traced the chronological evolution of one Arabic letterform – the lam-alif (which means ‘No’ in Arabic) – a thousand times to illustrate the common Arabic expression ‘No, and a thousand times no!’ The different letters were taken from Islamic artefacts and buildings produced under various patrons and Islamic dynasties over the last 1400 years, from Spain to the borders of China. A year earlier the curator at the Haus der Kunst had asked me to contribute a piece of art to the exhibition ‘The Future of Tradition – The Tradition of Future: 100 years after the Exhibition “Masterpieces of Muhammadan Art”’. Her one condition was that I use Arabic script in my work. I was assigned a wall in the gallery and given the freedom to choose any message I wanted. I knew the majority of my audience would not speak Arabic and would not be able to appreciate the beauty and the subtleties of the language. That said, I did not want them to read a translated message, and I certainly didn’t want to show them a set of meaningless letters. So I asked myself, if I had one thing to say to the world at this point in history what would it be? I decided to say ‘No’, a thousand different times.

When the Revolution started I felt helpless and useless. I started following the work of artists on the streets of Cairo. This is when I began thinking of my ‘Nos’ as ammunition. By using them in my work, I drew from 1,400 years of Arab and Islamic visual heritage and connected the historic Arabic script to contemporary issues. Each ‘No’ took its form from history, inspired by calligraphy inscribed on tombstones, walls, mosques and artefacts of the past. My thousand ‘Nos’ became my visual voice for the Revolution.

I added a message to my historic ‘Nos’, making them relevant to today’s world, and finally I felt that I had something to contribute. I sprayed ‘No to Military Rule’; ‘No to Emergency Law’; ‘No to Postponing Trials’; ‘No to Military Trials’, ‘No to Stripping the People’; ‘No to Blinding Heroes’; ‘No to Snipers’; ‘No to Sectarian Divisions’; ‘No to External Agendas’; ‘No to Killing’; ‘No to Burning Books’; ‘No to Violence’; ‘No to Separation Walls’; ‘No to Conspiracy Theories’; ‘No to Bullets’; ‘No to Tear Gas’; ‘No to Aliens’; ‘No to Stealing the Revolution’; ‘No to a New Pharaoh’. No and a thousand times No!

‘No’ was not the only thing I sprayed on the street. In February 2012, 74 young men were killed at a football stadium after a match. They all seemed to be Ultras Ahlawy, fans of the Cairo-based Premier League football club Al Ahly. Rumours circulated that the regime wanted revenge for the Ultras’ participation in the Revolution. When the game finished, the lights were turned off, the doors were locked and the killers were ordered in. Omar Mohsen was a student of The American University in Cairo and was due to graduate that spring. He was one of the young men killed that night. I found a poem by Pablo Neruda scribbled in Arabic in a field hospital in Tahrir. It read: ‘You can crush the flowers but you can’t delay spring.’ I sprayed it on the streets for Omar and the other young men killed by a brutal regime.

Throughout 2011–12, I regularly took my daughters to the streets of Cairo to show them my work during the Revolution. Everything I was doing was for them, so it made sense that they should be the first to see my work on the street. I showed it to them as if we were at a gallery, explaining what I had painted and why.

For two years a visual dialogue took place on the walls of the city. Something would happen, and dozens of artists would go down to the streets and paint. After a year of being on the street we knew each other’s messages without knowing each other’s faces. The city felt alive. It felt like it had a voice of its own, and was having an ongoing conversation with its citizens. Then everything stopped. Everything was put on hold and a dramatic shift took place. Activists were imprisoned, killed, threatened and silenced. Any voice that opposed was silenced. Any voice that criticised was silenced. We stayed away from the streets. But it felt wrong, like someone stealing your voice after you’ve only just found it.

In 2015, I decided that if the streets of Cairo were no longer accessible to me then I would make the cities of the rest of the world my canvas. When invited to conduct a gallery show in Freiburg I seized the opportunity and took to the streets again. To my surprise, this small German city on the border with Switzerland had twelve walls on which local street artists were permitted to paint. An anti-Islamic wave was sweeping through Europe, and now my cause extended beyond my own city to the world at large. The ‘Nos’ that had been targeted towards specific events in Egypt now became international ‘Nos’, rejecting our current human condition: ‘No to Blood’; ‘No to Extremism’; ‘No to Discrimination’; ‘No to Borders’; ‘No to Killing’; ‘No to Fascism’, ‘No to Racism’; ‘No to Hatred’; ‘No to

Violence’; ‘No to War’; ‘No to Colonisation’; ‘No to Stupidity’; ‘No to Closed Minds’. Like the ‘Nos’ in Cairo, the international ‘Nos’ first sprayed in Freiburg were taken from calligraphic inscriptions on historic buildings across the world: the Karatay Madrasa in Konya, Turkey; buildings and cenotaphs in Cairo; ceramic plates made in Nishapur and Samarkand; a minaret in Afghanistan; and Persian manuscripts now housed at a collection in New York.

We are united by our humanity and our suffering, even those people living in the most developed of countries. When geography was no longer an issue I felt liberated – I used my freedom of movement to help spread my messages. The new series of ‘Nos’ travelled with me to different cities: New Orleans, Istanbul, New York, Tokyo and Vancouver. But there came a point when I found that painting ‘Nos’ was not enough. I had other messages I wanted to share. And it is here

![]()

Vancouver:

When meeting

When meeting someone new it was sometimes difficult to answer the simple question: ‘What do you do?’ When I first started taking to the street, it was my habit to answer by saying, jokingly, ‘You mean by day or by night? By day I’m an educator and a scholar, by night I’m a street artist.’ I used invitations to academic conferences as opportunities to paint in different cities. Suddenly I was visiting corners of cities that I never would have set foot in had I not been thinking like a street artist. Marginalised areas, side alleys and slums became my canvases. In Cairo, I usually sprayed between 2 and 4am because...