![]()

PART I

Environmental and Socioeconomic Context

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Environmental Features

GEORGE A. PIERCE

INTRODUCTION

Human efforts to produce or procure food in the Near East through foraging or farming stretch back to the dawn of time and have been greatly influenced by environmental features such as topography, soils, availability or proximity to water, and climate. To use Annales terminology, the areas exploited for agriculture and pastoralism and also the settlement processes connected to food production are part of the longue durée in the area, whereas changes in land use, field systems, or crop choice may represent part of the centuries-long moyen durée or short-term événements.1 With such a longue durée perspective on climate and geography, settlement processes and food production in ancient Israel are part of a larger narrative in the southern Levant and the wider ancient Near East. Thus, environmental features that influenced food production also affected the location and size of settlements while human efforts sought to maximize or mitigate these influences as necessary.

Since an understanding of the ancient environment helps to explain settlement dynamics and food production, an appreciation for environmental features is necessary to situate archaeological sites and entities like ancient Israel within their physical landscapes and past climate regimes (Vita-Finzi 1978: 7). Thus, the archaeological record can serve as “a proxy for human biological and cultural evolution that identifies behavioral patterns encoded in artifacts and embedded in sediments” (Butzer 2008: 403–4), complementing the description of the physical environment found in textual sources and associated symbolism. Therefore, this chapter will discuss regional topography and its effect on settlement location and agropastoral economies, illuminate the relationship between a site and nearby soils and hydrology, and attempt to synthesize data about the ancient environment in a longue durée perspective to recognize how environmental factors played a role in food production as seen in the archaeological record and the text of the Hebrew Bible.

REGIONAL TOPOGRAPHY AND DIFFERENTIATION

A region is “determined by a complex of climatic, physiographic, biological, economic, social, and cultural characteristics” (Forman and Godron 1986: 13). Using this definition, the southern Levant can be divided into four main zones with several distinct regions, namely the Coastal Plain, the Central Mountains, the Jordan Rift, and the Transjordan Highlands (Aharoni 1979: 21–42). Within these zones, certain regions are delineated based upon physical and cultural geography, including underlying geology and soils (see Figure 1.1). For reference, they are often designated by the Israelite territorial allotments delineated in Joshua 13–21 and other polities mentioned in the Hebrew Bible (see Rainey and Notley 2007: 18–22). The Coastal Plain can be subdivided, from north to south, into Phoenicia, the Sharon Plain, and Philistia, while the Central Mountains include the Lebanon range, Galilee, the Jezreel Valley, Mount Ephraim, the Judean Hill Country, and the Shephelah (the foothills of western Judah bordering Philistia and the coastal plain). South of the Shephelah and the Judean hills, the Negev consists of the Beersheba-Arad Rift, mountains in the center, with the Gulfs of Suez and Aqaba/Eilat at the southern end. The Jordan Rift includes the subregions and features extending from Mt. Hermon through the Lake Huleh basin, the Sea of Galilee, the Jordan River, Dead Sea, and the Aravah. Biblically, Transjordan is divided into Bashan in the north, Gilead, which was the predominant area of Israelite settlement east of the Jordan River, and the territories of Ammon, Moab, and Edom.

FIGURE 1.1 Map of the southern Levant with regions, water features, and sites mentioned in this chapter. (Map by author)

Each of the larger zones had different cultural and economic focal points and presented unique challenges to settlement and food production. For example, the coastal plain extending from the Rosh ha-Niqra ridge southward and interrupted by the Carmel Ridge is 21 percent of the land of modern Israel (Kallner and Rosenau 1939: 61), but the area suitable for ancient agricultural activities without the benefits of fertilizer or irrigation is limited due to marshes, sand dunes, and soil types. Despite these limitations, the coastal plain served as the land bridge between Egypt and Mesopotamia due to the trunk road leading from the passes through the Carmel Ridge to Sinai and Egypt while also providing a gateway to the Mediterranean via the ports at regular intervals from Tyre to Gaza (Raban 1985: 11). Upper Galilee, while mountainous and densely forested in antiquity, provided many flat areas with springs that afforded suitable places for settlement. Lower Galilee, with four major east-west valleys, served as a thoroughfare for commerce from the eastern regions passing through the Jordan Valley headed for coastal sites like Achziv and Acco. The Central Mountains south of the Jezreel Valley consisted of the territories of Manasseh, Ephraim, Benjamin, and Judah during the biblical period, and while east-west travel is more difficult except on the Benjamin plateau, north-south travel can be accomplished by following the watershed. The terraced hills and valleys of the central range from Manasseh to Judah testify to the measures needed to successfully produce food. Hillsides were terraced for viticulture and horticulture. Areas under 10 degrees of slope, usually valleys, were utilized for cereals and other crops. Stager (1985: 5–9) posits that Iron Age settlers widely employed terracing in the region, although the practice may have been utilized before this period (Sayej 1999: 206–7). Nonenvironmental aspects such as trade via the valley routes also aided in settlement stability, but the same roads could allow foreign powers to invade and subjugate (Aharoni 1979: 26).2

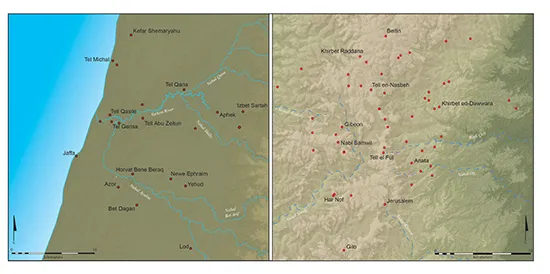

FIGURE 1.2 Map showing the contrast between Iron Age lowland sites (left) and highland settlement locations (right). (Map by author)

The topography of the four major zones and various subregions of ancient Israel affected the placement of settlements (see Figure 1.2). In flatter areas like the coastal plain, sites were located in places with access to the water table or a natural drainage such as a wadi, a seasonal stream bed, or a permanent river to maximize access to agricultural land following Middle and Late Bronze Age settlement patterns (Yasur-Landau, Cline, and Pierce 2008: 66, 77). Sites founded in the central hills during the Iron Age were typically situated on hilltops with terraced hills below (Stager 1982: 116; 1985: 6). However, topography was only one factor affecting settlement location and food production in ancient Israel. Soil and hydrology, together with climate, often played greater roles in affecting food production and procurement in ancient societies.

GEOLOGY AND SOILS

Archaeological sites with agropastoral economies required water sources and arable land. Differences in topography, geology, and soils differentiate each region inhabited by ancient Israel. Soils and the underlying lithology greatly influenced premodern agriculture based on their fertility and drainage capabilities. Rather than being areas of homogeneous soil, each region has a variety of other soils due to differences in underlying geology. Alluvial soils, deposited by runoff and wadi deposition from Upper and Lower Galilee and the central hill country of Ephraim and Judah, also provide a fertile base for agriculture along the coastal plain, the valleys throughout Galilee, and the central hills. These soils require water management to control drainage since excess water can cause soil deterioration (Dan et al. 1972: 42). Except for alluvium in the Huleh basin and Jordan valley, the underlying geology of the land east of the Jordan Rift is basalt with brown Mediterranean soil and basaltic lithosols, soils consisting of weathered rock fragments, overlying the ancient lava flows. These soils have primarily been used in the historical era for fruit and field crops with some grazing (Dan et al. 1972: 41).

The mountains of Upper Galilee, the Carmel Ridge dividing the coastal plain, and the central hills of Ephraim and Judah are composed primarily of Cenomanian limestone, the geologically oldest limestone in the region, with overlying Senonian or Eocene chalk or limestone and dolomite in sedimentation. Terra rossa soil, a clayey-silty soil with neutral pH, is also known as “red Mediterranean soil” and largely occurs with outcrops of limestone and dolomite in the central and northern hills of Israel, forming when rainwater leaches carbon and silicates from the parent rock, leaving soil abundant in iron hydroxides (Dan 1988: 107, 114). This soil is preferred for agriculture, especially for vines in wine production. In addition to cultivars, terra rossa is dominated by Kermes oak (Quercus calliprinos) and terebinth (Pistacia palaestina) and has been used as rangeland in certain areas. Rendzina, a clay-loam composite suitable for horticulture and viticulture, is prevalent in the Judean Shephelah with shallower areas of soil on rocky outcrops used for grazing (Dan et al. 1972: 38).

Besides the alluvium deposited along the rivers and wadis draining into the Mediterranean Sea, the coastal zone south of Carmel is predominantly composed of sandstone with overlying hamra soil, a reddish sandy loam, and sand dunes in the south with intermittent marshes north of the Yarkon River. Pleistocene coastal landscapes are represented by carbonate-cemented quartz sandstone called kurkar (Goldberg 1995: 49). Kurkar occurs in ridges parallel to the coast with older formations eastward, and these ridges are likely instances of former shorelines. These shore-parallel ridges decrease in number from seven in the south to two in the north (Ronen et al. 2005: 188). Moderately fertile hamra soils originate from coastal sand and kurkar in addition to alluvial sediments and are typical for the central coastal plain (Dan 1988: 117–18). Low hills of red hamra inland from the kurkar ridges are separated from the hills of Samaria farther east by an alluvial trough valley as wide as 6 km that runs southward to the Yarkon River basin.

The sand of the coastal plain consists of unconsolidated dune sand originating in the Nile Delta and transported by water and wind currents for the last million years (Dan 1988: 125; Ronen et al. 2005: 188). At the onset of the Middle Bronze Age (ca. 1950 BCE), people began to settle on the kurkar formations along the coast, and the sea level was 1–2 m lower than present (Sivan, Eliyahu, and Raban 2004: 1046). It was also at this time that wind-blown sands began to be deposited along the coast. The youngest sand deposits are post-Roman period in date, given their coverage of Late Roman and Byzantine sites and the presence of Early Islamic and Crusader period burials in the stabilized dunes, although some ingression of sand occurred after the Middle Ages (Neev, Bakler, and Emery 1987: 23).

The biblical Negev, the northern portion of the modern Negev, is a semi-arid marginal zone situated between areas receiving 300 mm of rain to the north and 100 mm to the south. The Negev is covered by loessial soils deposited by wind. With an average rainfall of 225–250 mm per year, agriculture, as practiced by residents in antiquity, would have been difficult without management of the winter rainfall. Historically, areas that were cultivated were primarily planted with cereals (Dan et al. 1972: 43). Settlements were mainly located along wadi channels to utilize the water that collected in the seasonal riverbeds (Aharoni 1979: 26).

The variety of soils in the immediate exploitation area of the site was a likely factor in determining settlement location and sustaining different activities. Webley (1972: 170) classified soils based on arability or grazing potential. Colluvial-alluvial, terra rossa, and Mediterranean brown forest soils provide the best suitability for agriculture, while alluvium (soil deposited by water), vertisols (heavily clay soils with little organic matter), and rendzina are less arable. He also posited that sites with long occupational histories have a maximum diversity of soil types available for exploitation, citing Hazor’s location near six soil types and the nearby Huleh basin as an example (Webley 1972: 170). Examination of the soil and settlement distribution for several regions in various periods from the Early Bronze Age through Iron Age II largely confirms this hypothesis, but other strategic or ritual factors could also be causal (Pierce 2005: 18–19; 2015; Yasur-Landau, Cline, and Pierce 2008).

HYDROLOGY

An examination of the surface hydrology of the southern Levant, both seasonal and permanent, reveals their importance for the ancient inhabitants of each region. Two central hydrological features of the area, in addition to the bodies of water in the rift valley (Lake Huleh, Sea of Galilee, and the Dead Sea), are the drainage systems that consist of the permanent Jordan River fed by three rivers emerging from Mt. Hermon and southern Lebanon (the Dan, Hasbani, and Banias Rivers) and several streams, and the Yarkon River (Nahr el-’Auja), which includes the seasonal Ayalon River (Wadi Musrara) and other wadis that drain into the Yarkon basin. Such stability would have influenced the decision to establish a settlement near one of these systems or their seasonal tributaries. The springs at Rosh Ha-‘Ayin (Aphek-Antipatris), from which the Yarkon River emerges, are the second most stable water source in Israel after the Jordan River, producing as much ...