Psychology

Carl Wernicke

Carl Wernicke was a German neurologist known for his work on the localization of brain function. He is particularly famous for identifying the area in the brain associated with receptive language, now known as Wernicke's area. His research laid the foundation for understanding the neurological basis of language and has had a lasting impact on the fields of psychology and neuroscience.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

8 Key excerpts on "Carl Wernicke"

Learn about this page

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.

- eBook - ePub

A History of the Brain

From Stone Age surgery to modern neuroscience

- Andrew P. Wickens(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Psychology Press(Publisher)

9 he was able to predict the consequences of their damage. Using little more than his imagination, Wernicke reasoned if a patient had damage to this connection, they would still be able to comprehend language since the ‘sound area’ of the temporal lobe was intact. In addition, the same person would have fluent speech as the frontal motor area still functioned normally. The deficit, therefore, must involve the passing of linguistic information, and Wernicke deduced this would manifest itself by the person being unable to fluently or accurately repeat words spoken to them. We now know Wernicke was remarkably prescient. Patients with this type of brain damage (i.e. to the arcuate fasciculus) do indeed have problems repeating verbal material, especially abstract words, despite being fully aware of their mistakes. Today, this type of neurological condition is called conduction aphasia.Source: National Library of Medicine.FIGURE 9.3 (A) Carl Wernicke (1848–1904). German doctor who discovered a second language centre in the temporal lobes in 1874 involved in verbal comprehension.Source: From Wernicke 1874.FIGURE 9.3 (B) The processing of language envisaged by Wernicke, which shows the acoustic nerve projecting to a centre for language comprehension (labelled a) and a centre for motor imagery and production (labelled b) extending to brainstem areas.Wernicke’s theory had shown how language and cognition could be modelled by integrating neuroanatomy with clinical observation, and it also made a number of other predictions that were testable through observation and experimentation. One of these concerned the possibility of a brain region specifically responsible for the encoding of written words (i.e. reading). Wernicke suspected this site lay close to the speech comprehension area in the temporal lobes. He was proved correct in 1892 when Frenchman Joseph Dejerine described a patient who suddenly lost the ability to read, despite having no obvious visual deficit. The autopsy revealed a stroke to the angular gyrus – a site lying between the visual cortex and the temporal ‘sound area’. Wernicke’s model of language processing was not only accurate, but it has proven remarkably enduring, with its basic tenets still accepted today.10 In addition to his work on aphasia, Wernicke described other medical conditions, including one resulting from thiamine deficiency commonly found among alcoholics. Today, this is known as Wernicke’s encephalopathy . He also found time to write a textbook entitled Foundations of Psychiatry - eBook - ePub

The Neurolinguistics of Bilingualism

An Introduction

- Franco Fabbro(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Psychology Press(Publisher)

In 1874 a young German neurologist, Carl Wernicke, published a short monograph entitled: “The aphasic symptomatic complex. A psychological study on an anatomical basis” (Wernicke, 1874/1974). This short book, only 72 pages long, was unusual for the German cultural style of that time, which was characterized by more voluminous neurological works, but it became one of the fundamental texts for the study of language disorders caused by cerebral lesions. The significance of this book lies in the fact that Wernicke not only described new cases of aphasia but also, on the basis of knowledge at that time, attempted to explain the way in which voluntary movement and language—a particular type of movement—were organized in the brain. Nowadays some of his explanations are simplistic and outdated, but certainly some intuitive ideas and the general framework of Wernicke’s theories are still valid and useful in the development of experimental and clinical studies on brain functions. Wernicke learnt and developed many of the ideas expressed in his book during his stay in Vienna with Theodor Meynert, a renowned clinical neurologist. In fact, in the preface to his book Wernicke writes that “whatever will be considered of value in the present book is to be ascribed to Meynert”. Subsequent neurological studies substantiated Wernicke’s acknowledgment. Indeed, most of Wernicke’s theories on cerebral organization of language had already been published a few years earlier by Meynert in a medical review in Vienna (Whitaker & Etlinger, 1993; Whitaker, 1998).Wernicke proposed that the cerebral cortex was organized in a system of very simple psychic functions, for instance in areas accounting for visual perception, in areas accounting for olfactory perception, and in areas accounting for tactile perception. These areas were anatomically connected. In Wernicke’s opinion, such an organization could explain memory - eBook - ePub

- Simon Greene(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Psychology Press(Publisher)

Separation of the angular gyrus/visual cortex system from Wernicke’s area prevents reading but leaves speech and writing intact. Damage to the arcuate fasciculus leaves language comprehension and production systems intact but desynchronised.Shortly afterwards Carl Wernicke (1874) reported on a series of patients who suffered from a different form of aphasia. They could speak in organised and grammatical sentences, although what they said often had little connection with the ongoing conversation. On the other hand they seemed to have little or no understanding of words that were spoken to them, failing to comprehend instructions, to answer simple questions, or to repeat words spoken to them. When their brains were examined at autopsy, they all had damage to an area at the top of the left temporal lobe. This type of aphasia is known as receptive or sensory aphasia, or sometimes Wernicke’s aphasia, and the area of temporal lobe implicated by Wernicke is known, quite reasonably, as Wernicke’s area (see diagram on previous page).These were the first aphasic syndromes to be described and related to particular parts of the cortex. Since then the work of Broca and Wernicke has been extended and refined, but their original ideas have stood the test of time remarkably well. Broca’s aphasia is now thought to require damage to cortical and subcortical regions extending beyond the classical Broca’s area but otherwise their work stands as a basic model of speech processes and the brain.The speech zones they identified also fit in with the sensory and motor cortical mechanisms described in the last chapter. Wernicke’s aphasia represents a problem with the processing of speech input. As a “sound” stimulus the spoken word enters our ears and eventually the neural representation (trains of nerve impulses in the auditory nerve) reaches the primary auditory cortex in the temporal lobe. This area is close to Wernicke’s area, which is where the “word analyser”, containing the auditory or sound patterns of words essential to converting speech sounds into words, is located. If Wernicke’s area is damaged, this processing cannot take place and the sounds cannot be identified as speech and comprehended. - eBook - ePub

- John Stirling(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

pure word deafness. In this condition, people can hear speech, but they cannot understand it. Recent anatomical and imaging research has shown that pure word deafness probably results from damage either to Wernicke’s area itself, or to the pathway connecting Hechl’s gyrus to it. Wernicke’s aphasia, on the other hand, depends on damage to more extensive cortical regions where the temporal and parietal lobes converge, and to the white matter underlying Wernicke’s area (Dronkers 1996).Evaluation of the neurological approach to language

The study of language impairment in people with brain damage has provided a wealth of information about the role(s) of left-sided cortical regions involved in mediating language. The types of aphasia identified over 100 years ago are still seen today, and careful case study has thrown up several other forms of language disorder which can be related to lesions/damage to other components of the brain’s language system. On the other hand, human brain damage is, inevitably, highly variable. Recent research has led psychologists to conclude that the forms of aphasia identified by Broca and Wernicke probably depend on more extensive damage to either frontal or posterior regions than was initially thought. Also, it appears that several other ‘centres’ (and interconnecting pathways) in addition to Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas and the arcuate fasciculus are involved. These contribute to a distributed control network that is responsible for the full range of language skills. Finally, it is worth mentioning again that there is potential danger in relying on the study of damaged brains to form an understanding of normal brain function.The psycholinguistic approach

Psycholinguistics is, primarily, the study of the structure of language in normal individuals, rather than the study of language impairments of neurological patients. As the discipline grew, researchers developed theories about the form and structure of language relatively independent of the neurological work described in the previous section. Indeed, it would be fair to say that, initially at least, the two approaches represented quite distinct levels of inquiry into the study of language. The psycholinguistic approach is essentially ‘top-down’, whereas the neurological approach is very much ‘bottom-up - eBook - ePub

Origins of the Modern Mind

Three Stages in the Evolution of Culture and Cognition

- Merlin Donald(Author)

- 1993(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

The early discoveries of Broca (1861) and Wernicke (1874) served as the foundation stones of localizationist models of language. Broca (1861) described the symptoms of expressive aphasia and linked them to the third left inferior frontal convolution of the cerebral cortex, now called Broca’s area. Although others had made the same claim, Broca brought the syndrome into the mainstream of neurology by suggesting that language was controlled from a specific brain region. Broca’s initial model claimed that language was independent of other brain functions (since it could be damaged in isolation from other mental functions) and that it was localized in a particular part of the brain. From a Darwinian standpoint, this made good sense. The tertiary areas of the frontal cortex, of which the speech areas form a part, are a distinctly human evolutionary development. Broca’s proposal thus implied (although he did not explicitly state this) that speech was a unitary skill, dependent upon a special feature of human brain anatomy that had evolved especially to support speech.Broca’s proposal ran into trouble almost immediately. The main problem was that language did not always break down in the same way. It was soon pointed out (Bastian, 1869) that visual language—namely, writing and reading—could be affected by brain damage quite independently of speech. This required that speech and visual language be treated separately in terms of underlying brain anatomy, but it did not completely undermine Broca’s proposal. However, in 1874 Wernicke struck an apparently fatal blow to Broca’s theory: he described a second, distinctly different kind of aphasia, fluent aphasia, that could be attributed largely to the destruction of part of the first temporal gyrus, now called Wernicke’s area. The existence of at least two language areas concerned with speech led Wernicke to suggest a different kind of language model, one which treated speech as a complex of several underlying systems rather than as a unitary system. In his model the sound images of speech were stored in Wernicke’s area and were sent along a neuronal pathway to Broca’s area, which supposedly contained the detailed instructions for the articulation of speech sounds. Other fiber paths connected Wernicke’s area not only to the frontal speech region but also to the various input modalities of language. This allowed Bastian’s (1869) observations on dyslexia and agraphia to be accounted for, and it also led Wernicke to predict the effects of severing the fiber pathways between regions, the so called disconnection syndromes. He predicted the existence of conduction aphasia, a disorder of repetition that results from severing the most direct path from Wernicke’s area to Broca’s area. - eBook - ePub

Your Brain, Explained

What Neuroscience Reveals about Your Brain and its Quirks

- Marc Dingman(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Nicholas Brealey Publishing(Publisher)

But when a hypothesis about how the brain works seems too simple, it usually is, and most experts today agree that the classic model is deficient in some way. One common complaint is that we now have overwhelming evidence that language—which, rather than consisting of just comprehension and production, involves a long list of sub-tasks ranging from selecting words to incorporating syntax to initiating speech-related movements—requires input from many more brain areas than the classic model suggests. Far from being a function that’s localized to two brain regions and the major pathway that connects them, language seems to be distributed across much of the cerebral cortex—on both sides of the brain—as well as the thalamus and other structures we’ll be discussing later in the book like the basal ganglia, cerebellum, and more. And the involvement of these many brain areas by necessity must mean that there are multiple pathways that have to be recruited to connect the diverse regions.Another criticism is that, despite the reliance on Broca’s and Wernicke’s area as cornerstones of language in the brain, there is no precise definition—anatomical or functional—of either of these areas. To illustrate this, language researchers Pascale Tremblay and Anthony Dick conducted a survey in 2015 of neurobiologists who study language, and asked them to pinpoint the locations of Broca’s and Wernicke’s area in the brain. The respondents were divided when it came to Wernicke’s area: their votes were spread across seven different locations, and none of the proposed sites garnered more than 30 percent of the votes. Broca’s area fared slightly better: one location got 50 percent of votes, but the rest of the votes were distributed across six other regions.11Our functional definitions of Broca’s and Wernicke’s area also are a bit unsettled. It has become dogma that Broca’s area is involved with speech production. But the exact role of Broca’s area in producing speech is still uncertain. Is it, for example, critical to generating motor movements that produce speech? Or is it involved with verbal memory? Or syntax? Or grammar? Or all of these? The answer is unclear. - eBook - ePub

Talking Heads

The Neuroscience of Language

- Gianfranco Denes, Philippa Venturelli Smith(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Psychology Press(Publisher)

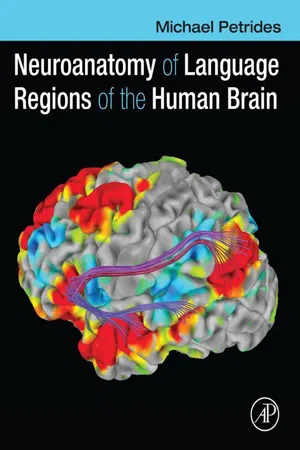

Some years later, Fritsch and Hitzig (1870) demonstrated, in dogs, that electrical stimulation of the frontal area of one hemisphere produced isolated limb movement on the opposite side of the body. There was, moreover, constant correspondence between the area of the cortex undergoing stimulation and the location of the resulting movement. This effect was not witnessed when posterior areas of the cortex were stimulated. In the years that followed, experiments on dogs and other mammals demonstrated that auditory and visual deficits followed lesions to the occipital and temporal lobes. These findings led to the development and consolidation of the notion of cerebral localization of sensory and motor functions.Figure 3.1 Photographs of the brains of Leborgne and Lelong, Broca’s first aphasic patients. (a) The lateral surface of the first patient, Leborgne. The lesion is clearly visible at the height of the inferior section of the frontal lobe. The softening of surrounding superior and posterior regions suggests further cortical and subcortical involvement. (b) Enlargement of Leborgne’s cerebral lesion. (c) The lateral surface of the second patient, Lelong. The size of the frontal, temporal and parietal lobes is reduced because of atrophy, allowing the insula to be seen. (d) Enlargement of Leborgne’s cerebral lesion. It can be seen that the lesion is limited to the posterior area of what we now call Broca’s area, while the anterior area is undamaged (from Dronkers et al., 2007). Reproduced with permission of Oxford University Press.Finally, the fact that around 90% of people show a right-handed preference (Annett, 1982, 1985) under the control of the left hemisphere, led to the conclusion that the left hemisphere is dominant over the controlateral right or ‘minor’ hemisphere, controlling two species-specific skills, language and handedness. It was only later discovered that the right hemisphere was critical for processing a variety of non-verbal cognitive skills (for a review see Denes & Pizzamiglio, 1999).The most important contribution to the development of a neurological model of language was made by a German neurologist, Karl Wernicke, who, in 1874, published a monograph with an extremely significant title: The Aphasic Symptom Complex: A Psychological Study on an Anatomical Basis . Wernicke propounded a model of neurological language processing based on the principles of the functional and anatomical organization of the cerebral cortex proposed by his mentor Theodor H. Meynert: motor functions are represented in the frontal and prefrontal anterior areas of the cerebral cortex, while the processing of sensory stimuli takes place in the parietal, temporal and occipital lobes. To be more precise, acoustic stimuli are processed in the temporal lobes, and visual stimuli in the occipital lobes, while the parietal lobes have the task of analysing thermal, tactile and pain stimuli. Meynert also divided the primary areas from secondary, or association, areas. Each sensory modality projects to a specific primary cortical area where information from the sensory receptors is perceived. The product of this initial analysis is then sent to the specific association areas where it is stored. In this way recognition is possible, through a match between information elaborated in the primary areas and images deposited in the specific association areas. The same procedure occurs for motor functions: the specific patterns for the various motor acts are deposited in the motor association area and are transmitted, when needed, to the primary motor area for execution. The complex of secondary areas can, therefore, be seen as the store for culturally learned information, which reaches the highest level of development in the human species (Figure 3.2 - Michael Petrides(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Petrides et al., 2005 ). Clearly, they are not used in language processing sensu stricto, although we can assume that their fundamental neural computations were essential to support language as it began evolving in the human brain. For further discussion of this issue, see last section on the connectivity of the language areas.Broca’s Region and Wernicke’s Region: Historical Considerations

The scientific exploration of the brain regions that are critically involved in language processing started with the influential observations made by Pierre Paul Broca in Paris in the latter part of the 19th century. In 1861, Broca presented the cases of the two now famous patients who exhibited severe speech production impairments after damage to the posterior part of the ventrolateral frontal lobe in the left hemisphere (Broca, 1861a , b , c ). The first case, Leborgne, was a 51 year old man who had lost his ability to speak several years earlier. When attempting to speak spontaneously or in response to questions, he managed to produce only the syllable “tan”. At autopsy, a large lesion was noted in the posterior part of the third frontal convolution (inferior frontal gyrus) of the left hemisphere (Fig. 1 ). Broca considered this finding to be consistent with the claim, intensely discussed in Paris at the time, that the frontal lobe is critical for language and presented this case to the Anthropological Society (Broca, 1861a ) and the Anatomical Society of Paris (Broca, 1861b ).FIGURE 1 Photographs of the lateral surface of the left hemisphere of the brains of Leborgne and Lelong to show the lesions in the inferior frontal gyrus. In Leborgne, the lesion extends beyond the inferior frontal gyrus and involves the nearby superior temporal region and the adjacent ventral anterior parietal region. Inspection of the expanded region (inset) allows one to appreciate the depth of the lesion, implying damage to the insula and adjacent basal ganglia. Dronkers et al., Paul Broca’s historic cases; high resolution MR imaging of the brains of Leborgne and Lelong, Brain, 2007, 130(5), pp. 1432–1441, by permission of Oxford University Press.