What is The Uncanny?

PhD, English Literature (Lancaster University)

Date Published: 01.11.2023,

Last Updated: 17.01.2024

Share this article

Definition and origins

In 1989, Agent Dale Cooper (played by Kyle MacLachlan) enters the town of Twin Peaks, hoping to solve the mysterious murder of homecoming queen Laura Palmer. However, it soon becomes clear that beneath the small town’s quaint and unassuming appearance, everything is not as it seems. Featuring doppelgängers, anthropomorphism, zoomorphism, and a woman who talks to a log, David Lynch and Mark Frost’s Twin Peaks (1990–1991) epitomizes the uncanny: the uneasy, and sometimes terrifying, feeling produced when we encounter something which is oddly familiar.

As Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock writes of Twin Peaks,

A fish in a percolator. An ominous swaying traffic light. A sublime vista of neatly stacked doughnuts. A log that conveys secrets. A Dictaphone (possibly named Diane). Not one but two diaries. A human chess piece. A man who reminds another of a lapdog. Much of the strangeness of the world of David Lynch and Mark Frost’s Twin Peaks, its glorious and disorienting off-kilterness, inheres in its uncanny representation of matter—things out of place, things saturated with affect, defamiliarized things, inspirited things. (“Wondrous and Strange: The Matter of Twin Peaks,” 2015)

Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock & Catherine Spooner

A fish in a percolator. An ominous swaying traffic light. A sublime vista of neatly stacked doughnuts. A log that conveys secrets. A Dictaphone (possibly named Diane). Not one but two diaries. A human chess piece. A man who reminds another of a lapdog. Much of the strangeness of the world of David Lynch and Mark Frost’s Twin Peaks, its glorious and disorienting off-kilterness, inheres in its uncanny representation of matter—things out of place, things saturated with affect, defamiliarized things, inspirited things. (“Wondrous and Strange: The Matter of Twin Peaks,” 2015)

In this serial drama, the uncanny is used to create feelings of unsettling terror in the viewer; something about the town of Twin Peaks, from the perspective of out-of-towners like us, is not quite right.

As exhibited by Twin Peaks, the uncanny can be described as the feeling we experience when a certain event, person, or place is strangely familiar, or when the familiar is made strange; this eerie feeling may unsettle or frighten us. The term was first used by psychologist Ernst Jentsch in his essay “On the Psychology of the Uncanny” (1906) and was later developed by Sigmund Freud in his essay “The Uncanny” (1918) (reprinted in The Uncanny, 2003). Jentsch’s essay was published across two issues of the Psychiatrisch‐Neurotogische Wochenschrift and explores how the uncanny (or unheimlich in German) arises from what is uncertain.

Though exact definitions of the uncanny differ, Jentsch’s core ideas are still present in scholarship analyzing the impact of the uncanny in Gothic literature, art, digital media, and robotics. This guide will go on to explore how Jentsch and Freud define the uncanny, and representations of the uncanny from the nineteenth century to today.

Jentsch and the unheimlich

Discussing the word “unheimlich,” Jentsch writes,

Without a doubt, this word appears to express that someone to whom something ‘uncanny’ happens is not quite ‘at home’ or ‘at ease’ in the situation concerned, that the thing is or at least seems to be foreign to him. In brief, the word suggests that a lack of orientation is bound up with the impression of the uncanniness of a thing or incident. (in Uncanny Modernity, 1906, [2008])

Edited by Jo Collins & J. Jervis

Without a doubt, this word appears to express that someone to whom something ‘uncanny’ happens is not quite ‘at home’ or ‘at ease’ in the situation concerned, that the thing is or at least seems to be foreign to him. In brief, the word suggests that a lack of orientation is bound up with the impression of the uncanniness of a thing or incident. (in Uncanny Modernity, 1906, [2008])

Jentsch argues that it is difficult to provide a succinct explanation for the uncanny and, as such, it is better to discuss the psychological impact and feelings that arise as a result of experiencing the uncanny. Jentsch explains that,

It is thus comprehensible if a correlation ‘new/foreign/hostile’ corresponds to the psychical association of ‘old/known/familiar’. In the former case, the emergence of sensations of uncertainty is quite natural, and one’s lack of orientation will then easily be able to take on the shading of the uncanny; in the latter case, disorientation remains concealed for as long as the confusion of ‘known/self-evident’ does not enter the consciousness of the individual. (in Uncanny Modernity, 1906, [2008])

It is quite normal, as Jentsch points out, to feel disorientated in an unfamiliar situation. It is when we feel this sense of unfamiliarity or uncertainty when we are in environments or situations known to us that produces the sensation of the uncanny. Jentsch highlights that such feelings arise when people visit wax museums, as “in semi-darkness it is often especially difficult to distinguish a life-size wax or similar figure from a human person” (1906, [2008]). Wax figures, porcelain dolls, and lifelike robots can create feelings of unease as they are familiar and yet there is something clearly not human about them. This uncertainty, Jentsch argues, can be effectively harnessed by writers and artists:

In storytelling, one of the most reliable artistic devices for producing uncanny effects easily is to leave the reader in uncertainty as to whether he has a human person or rather an automaton before him in the case of a particular character. (in Uncanny Modernity, 1906, [2008])

Here, Jentsch specifically refers to “The Sandman” (1816), a short story by E. T. A. Hoffman, in which the protagonist, Nathanael, falls in love with Olimpia who, unbeknownst to him, is a doll-like automaton. In the text, Nathaneal’s friend grows concerned about Olimpia, suspecting there is something inhuman about her:

“[Olimpia] is strangely measured in her movements, they all seem as if they were dependent upon some wound-up clock-work. Her playing and singing has the disagreeably perfect, but insensitive time of a singing machine and her dancing is the same. We felt quite afraid of this Olimpia, and did not like to have anything to do with her; she seemed to us to be only acting like a living creature, and as if there was some secret at the bottom of it all.” (1816, [2018])

E. T. A. Hoffmann

“[Olimpia] is strangely measured in her movements, they all seem as if they were dependent upon some wound-up clock-work. Her playing and singing has the disagreeably perfect, but insensitive time of a singing machine and her dancing is the same. We felt quite afraid of this Olimpia, and did not like to have anything to do with her; she seemed to us to be only acting like a living creature, and as if there was some secret at the bottom of it all.” (1816, [2018])

Olimpia’s lack of humanity, her strangely accurate gestures and movements, evoke a sense of fear and suspicion. This uncertainty, for Jentsch, is at the core of what creates sensations of the uncanny:

The human desire for the intellectual mastery of one’s environment is a strong one. Intellectual certainty provides psychical shelter in the struggle for existence. [...] the lack of such certainty is equivalent to lack of cover in the episodes of that never-ending war of the human and organic world [...] (in Uncanny Modernity, 1906, [2008])

The uncanny, then, disorientates us and makes us challenge the reality of the world around us.

Freud and the return of the repressed

Freud objected to some of Jentsch’s conclusions about the uncanny and its definition. In his essay “The Uncanny,” he expands upon the etymology of the word. Freud writes,

The German word ‘unheimlich’ is obviously the opposite of ‘heimlich’ [‘homely’], ‘heimisch’ [‘native’] – the opposite of what is familiar; and we are tempted to conclude that what is ‘uncanny’ is frightening precisely because it is not known and familiar. Naturally not everything that is new and unfamiliar is frightening, however; the relation is not capable of inversion. We can only say that what is novel can easily become frightening and uncanny; some new things are frightening but not by any means all. Something has to be added to what is novel and unfamiliar in order to make it uncanny. (in Literary Theory, 1918, [2017])

Edited by Julie Rivkin & Michael Ryan

The German word ‘unheimlich’ is obviously the opposite of ‘heimlich’ [‘homely’], ‘heimisch’ [‘native’] – the opposite of what is familiar; and we are tempted to conclude that what is ‘uncanny’ is frightening precisely because it is not known and familiar. Naturally not everything that is new and unfamiliar is frightening, however; the relation is not capable of inversion. We can only say that what is novel can easily become frightening and uncanny; some new things are frightening but not by any means all. Something has to be added to what is novel and unfamiliar in order to make it uncanny. (in Literary Theory, 1918, [2017])

In short, the uncanny is not simply the opposite of what is homely and familiar; something else must be combined with the feelings of unfamiliarity to create uncanny effects. Freud states,

heimlich is a word the meaning of which develops in the direction of ambivalence, until it finally coincides with its opposite, unheimlich. ( in Literary Theory, 1918, [2017])

When we experience the uncanny, according to Freud, what is familiar gradually becomes more alien to us.

Freud argues that this faint recognition is caused by the return of the repressed. In Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, he argues that the unconscious mind contains thoughts and memories which have been repressed, and can only be accessed through psychoanalytic therapy. The repression of thoughts and memories, Freud argues, is the mind’s way of protecting itself against psychological trauma. When we experience the uncanny, according to Freud, it is because something is familiar for reasons we are unable to identify. This occurs due to our experience with something which is connected to, or reminds us of, our repressed memories. As Freud states, the uncanny is “something which is secretly familiar [...] which has undergone repression and then returned from it, and that everything that is uncanny fulfils this condition” (1918, [2017]).

Freud’s notion of the return of the repressed enables him to draw different conclusions from Hoffman’s short story than Jentsch. Freud argues that the uncanniness in “The Sandman” does not derive mainly from Olimpia, but the figure of the Sandman himself, a folkloric entity that removes the eyes of children who won’t go to sleep.

Freud argues that the fear of losing or harming one’s eyes is deeply entrenched and linked to fears of castration. Freud turns to the Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex to explain how the self-blinding of Oedipus is a “mitigated form of the punishment of castration”(1918, [2017]). This explanation is part of Freud’s theory of the Oedipus Complex. As such, when we encounter stories where eyes are removed, this creates a sense of the uncanny as losing our eyes, according to Freud, is a repressed fear from childhood.

Gothic doubles

Freud’s essay further details other instances which can give rise to the uncanny. In particular, Freud focuses on the presence of a double or doppelgängers. This unease is caused by a presumption that people who look alike, or even exactly the same, will have access to the thoughts and feelings of the other, like telepathy. Secondly, the person who sees another version of themselves may begin to strongly identify with their double to the extent to which they lose their sense of self. The terror of the double has been the basis for much Gothic fiction and contemporary horror. Freud writes,

This invention of doubling as a preservation against extinction has its counterpart in the language of dreams, which is fond of representing castration by a doubling or multiplication of a genital symbol. [...] Such ideas, however, have sprung from the soil of unbounded self‐love, from the primary narcissism which dominates the mind of the child and of primitive man. But when this stage has been surmounted, the ‘double’ reverses its aspect. From having been an assurance of immortality, it becomes the uncanny harbinger of death. (in Literary Theory, 1918, [2017])

Doubles, therefore, remind us of our own mortality, as well as what lies repressed within us. This figure made for fertile ground for Gothic writers in the nineteenth century. Doppelgängers can destablize a character’s sense of self in texts such as James Hogg’s The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824). The double in Victorian Gothic fiction often represents repressed desire, subconscious thoughts or feelings, or as a dissociated split self. We can see this in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in which Dr. Jekyll creates his double, Mr. Hyde. Freud argues that Hyde is an embodiment of the “primary narcissism” present in children and primitive beings (1918, [2017]). Jekyll’s double emerges as a “thing of terror” (1918, [2017]). The return of this repressed part of Jekyll creates the feeling of uncanniness as he is encountering an aspect of his forgotten past that has taken on a more malevolent and sinister aspect in adulthood.

Doppelgängers continue to be a staple of Gothic stories and are commonly used in horror cinema. For example, in Jordan Peele’s Us (2019), a family encounters their frightening doubles while on vacation. While the doubles are almost identical versions of the family, their sadistic behavior, altered movements, and inability to speak (or ability to speak only in raspy croaks in the case of the mother’s double, Red) render them uncanny. These monstrous versions of the family, referred to as “the tethered,” threaten to replace their counterparts.

The following is a clip from Peele’s film which perfectly captures the horror of the uncanny:

In addition to the traditional double which appears as a separate physical presence, the split self can also create uncanny effects. In Darren Aronofsky’s psychological thriller Black Swan (2010), ballet performer Nina experiences a splitting of her psyche, envisioning a dark double as a result of the pressures she faces in preparation for her role as the titular black swan. The viewer, much like Nina, spends a large proportion of the film wondering how much of what Nina is seeing is a hallucination.

Ghost stories

A further example of the Gothic uncanny can be seen in the haunted house. Haunting apparitions challenge home as a place which is safe and familiar in Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw (1898), and the appearance of haunting presences in novels such as Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847) and Charlotte Brontë’s Villette (1853) disturb the boundary between reality and fantasy, causing characters to question the rational and consider the possibility of psychic phenomenon. As Freud states,

an uncanny effect is often and easily produced when the distinction between imagination and reality is effaced, as when something that we have hitherto regarded as imaginary appears before us in reality, or when a symbol takes over the full functions of the thing it symbolizes, and so on. It is this factor which contributes not a little to the uncanny effect attaching to magical practices. The infantile element in this, which also dominates the minds of neurotics, is the over‐accentuation of psychical reality in comparison with material reality – a feature closely allied to the belief in the omnipotence of thoughts. (in Literary Theory, 1918, [2017])

We experience the uncanny when the fears that we have in childhood, that have since been repressed or rationalized in our adult lives, resurface in adulthood. The inability to distinguish between reality and fantasy produces these uncanny effects. As David Punter writes,

If we are afraid, then more often than not it is because we are experiencing fear of the unknown: but if we have a sense of the uncanny, it is because the barriers between the known and the unknown are teetering on the brink of collapse. We are afraid, certainly; but what we are afraid of is at least partly our own sense that we have been here before. (2007)

Edited by Catherine Spooner & Emma McEvoy

If we are afraid, then more often than not it is because we are experiencing fear of the unknown: but if we have a sense of the uncanny, it is because the barriers between the known and the unknown are teetering on the brink of collapse. We are afraid, certainly; but what we are afraid of is at least partly our own sense that we have been here before. (2007)

The affinity between Freud’s work and the Gothic is clear. After all, a large body of Gothic literature, both classic and contemporary, deals with the realization that what is deemed imaginary “appears before us in reality.” The Victorian ghost story is a clear example of this. As Emma Liggins states,

"Freudian notions of the uncanny and the familiar/unfamiliar distinction have become essential to our understandings of the nineteenth-century ghost story and the haunted house." (2020)

She further adds,

"The uncanny can be an experience of disorientation, or the feeling of being lost in an unfamiliar environment. These contradictory meanings of the term cluster around notions of space and spectrality, as if, paradoxically, intimacy and homeliness both incorporate and exclude the ghostly." (Liggins, 2020)

Emma Liggins

"Freudian notions of the uncanny and the familiar/unfamiliar distinction have become essential to our understandings of the nineteenth-century ghost story and the haunted house." (2020)

She further adds,

"The uncanny can be an experience of disorientation, or the feeling of being lost in an unfamiliar environment. These contradictory meanings of the term cluster around notions of space and spectrality, as if, paradoxically, intimacy and homeliness both incorporate and exclude the ghostly." (Liggins, 2020)

The idea that the home has become an unfamiliar space, or one which is susceptible to supernatural intruders, shifts our understanding of what we consider homely, rendering no space sacred or safe.

The uncanny in art

Numerous visual artists have sought to create a feeling of the uncanny with their work. An artist renowned for producing this eerie and unsettling effect is Ron Mueck. Mueck creates lifelike, often oversized, sculptures, including “In Bed” (Figure 1), “A Girl” (2006), and “Dead Dad” (1996–97). Mueck’s artworks are incredibly detailed, capturing liverspots, body hair, and textured skin. However, such works create a feeling of uncanniness, primarily due to the combination of these hyperrealistic details with the gigantic scale of the works themselves. “A Girl,” for example, depicts a newborn baby that is just over five meters in length.

(Fig. 1. In Bed, Ron Mueck. Photographed by Alexandre Van de Sande, 2005, Flickr)

We can also see the uncanny in the work of Sarah Lucas, who uses everyday objects to create the unsettling sensation of a body out of place. In the exhibition NUD Cycladic, Lucas displayed hosiery stuffed and arranged to create the illusion of intestines, or twisting limbs (Figure 2). This mass of what appears to be human and organic, combined with the synthetic material nylon creates a strange disconnect. Moreover, the experience of seeing these body parts, enlarged and outside of the body, can create feelings of abjection, a concern for the bodily integrity of the viewer.

(Fig. 2. “Untitled” by Sarah Lucas at the Museum of Cycladic Art. Photographed by Konstantinos Koukopoulos, 2010, Flickr.)

Artists drawn to creating uncanny works have often, like Mueck and Lucas, experimented with scale, media, and textures to create an unsettlingly familiar effect in the viewer.

The uncanny valley: robotics and digital media

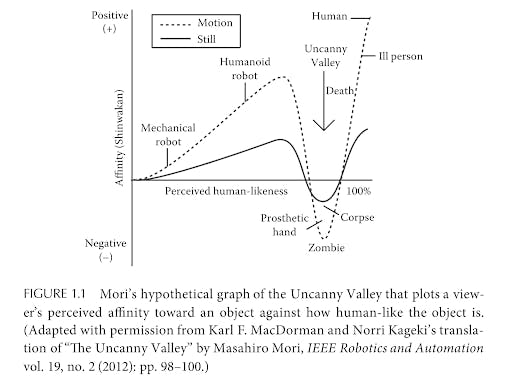

The uncanny valley is likely what the majority of people think of when asked about the uncanny. This concept was first discussed by robotics professor Masahiro Mori in his essay “Uncanny Valley” (1970, [2012]). The essay explains that robots designed to have a functional role working alongside engineers were off-putting to the engineers due to their mechanical features and movements. In response, human-like robots were created with the purpose of building a sense of rapport between the machines and the engineers and putting them at ease. Mori felt this attempt would be unsuccessful as the androids would not be able to fully replicate a human, making them appear unsettling.

Mori plotted a graph to represent how he predicted humans would feel towards robots depending on how lifelike the robot appeared. For example, as we can see on the graph (Figure 3), an industrial or mechanical robot is very unlike a human and thus humans will have a low affinity to the robot, not being able to recognize themselves in it or identify with it. As we move further along, people may have an increased affinity to things seen as more human such as dolls or toys. However, there is a certain point, Mori noted, where the robot becomes too lifelike yet too inhuman and affinity is lessened. This is particularly the case with corpses, prosthetic hands, and zombies as they are incredibly human-like, but not quite human. This dip — where something inanimate becomes so lifelike as to create a sense of uncanniness — is called “the uncanny valley.”

(Fig. 3. “Mori Uncanny Valley” in Angela Tinwell, The Uncanny Valley in Games and Animation, 2014 )

Movement can also impact whether we view something as canny or not. Mori writes that,

Since negative effects of movement are apparent even with a prosthetic hand, a whole robot would magnify the creepiness. And that is just one robot. Imagine a craftsman being awakened suddenly in the dead of night. He searches downstairs for something among a crowd of mannequins in his workshop. If the mannequins started to move, it would be like a horror story. (2012)

Examples of robots that many consider to be within the uncanny valley include Geminoid HI-1 (Figure 4), modeled after its creator, Hiroshi Ishiguro, in appearance, movement, and sound.

(Fig.4. “Hiroshi Ishiguro / Geminoid HI-4” Photographed by nrkbeta, 2016, Flickr)

Attempts to create lifelike characters can also be seen through the emergence of CGI (computer-generated imagery) in the early twenty-first century. In The Uncanny Valley in Games and Animation, Angela Tinwell examines the impact of CGI in films and games. In the film Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within (2001), Tinwell writes that,

The main protagonist character, Doctor Aki Ross, was designed to be regarded as an empathetic, human-like character, yet her jerky movements and unnatural and emotionally limited facial expression evoked an adverse reaction from the audience. Instead of being perceived as attractive and likeable, she was regarded as creepy and strange. (2014)

Angela Tinwell

The main protagonist character, Doctor Aki Ross, was designed to be regarded as an empathetic, human-like character, yet her jerky movements and unnatural and emotionally limited facial expression evoked an adverse reaction from the audience. Instead of being perceived as attractive and likeable, she was regarded as creepy and strange. (2014)

Tinwell further highlights the 2004 children’s animation The Polar Express had similar effects, with the unnatural movement of Tom Hanks’ character, the Conductor (2014).

Video game developers face similar challenges in conveying characters’ emotions and movements realistically. Tinwell points to Quantic Dream’s Heavy Rain:

[The] female protagonist was intended to evoke pity from the audience for her misfortune, yet viewers failed to empathize with her and were put off by her strange and bizarre behavior. The audience was also aware of a distinct asynchrony of speech with her lip movement. (2014)

In 2018, Quantic Dream released Detroit: Become Human, set in a world where androids and humans co-exist; the inclusion of non-human characters helped the developers sidestep the uncanny valley.

Video games, and other forms of digital media, have developed substantially in recent years, making encountering the uncanny less of a concern for creators. As we become acclimated to these advances in technology, the benchmark of what we consider to be uncanny shifts. This may have interesting implications for how we adjust to artificial intelligence as we approach a posthuman society. In The Unconcept, Anneleen Masschelein writes,

By heightening [robots’] uncanny qualities in fiction, we get used to them and may be prepared for their actual arrival in our posthuman world as the technology is perfected. The scientific literature dealing with human-robot interaction or with state of the art photo-realistic animation usually focuses on the realm of the service and the entertainment industries (movies and games). [...] This double drive, threatening and ludic at the same time, belatedly prepares us for technological innovations in our daily lives but also warns us never to be too much at home or at ease with technology. (2012)

Anneleen Masschelein

By heightening [robots’] uncanny qualities in fiction, we get used to them and may be prepared for their actual arrival in our posthuman world as the technology is perfected. The scientific literature dealing with human-robot interaction or with state of the art photo-realistic animation usually focuses on the realm of the service and the entertainment industries (movies and games). [...] This double drive, threatening and ludic at the same time, belatedly prepares us for technological innovations in our daily lives but also warns us never to be too much at home or at ease with technology. (2012)

We can see this today with discussions around artificial intelligence (AI), prompted largely by the popularization of ChatGBT. In addition, programs such as Colossyan enable the creation of AI videos with the use of avatars, intended for workplace learning. Our familiarity with digital media, CGI, and these newer forms of AI means that what we consider uncanny is evolving and adapting, according to our exposure to new technology.

Concluding thoughts

The presence of the uncanny in literature, art, and other media continues to fascinate us today. Objects and environments which give rise to the uncanny are manifold, crossing between fiction and reality. While some forms of media (such as video games) strive for verisimilitude to create a sense of immersion for players, some forms of media such as horror films aim to achieve the exact opposite: an unsettling familiarity that makes the reader question their pre-existing notions of what is real. Attempts to bring about or eschew the uncanny all point to one thing: the effect of the uncanny is powerful, producing feelings of terror, discomfort, or disgust. Whether it is a doppelgänger who destabilizes our sense of self or evokes feelings of repressed (and often taboo) desires, or the presence of something suspiciously abhuman, the uncanny works to distort the familiar and points to a concealed aspect of ourselves, and our history, that has been long forgotten.

Further reading on Perlego

On Freud's "The Uncanny" (2019) edited by Catalina Bronstein and Christian Seulin

Uncanny Bodies (2007) by Robert Spadon

The Queer Uncanny: New Perspectives on the Gothic (2012) by Pauline Palmer

Uncanny Histories in Film and Media (2022) edited by Patrice Petro

What is the uncanny in simple terms?

What is an example of the uncanny?

When do we experience the uncanny?

What is the uncanny valley?

Bibliography

Brontë, C. (2015) Villette. Harper Perennial. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/583886/villette-pdf

Brontë, E. (2012) Wuthering Heights. Dover Publications. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/110034/wuthering-heights-pdf

Freud, S. (2003) The Uncanny. Penguin.

Freud, S. (2017) “The Uncanny,” in Rivkin, J. and Ryan, M. (eds.) Literary Theory: An Anthology. Wiley-Blackwell. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/992490/literary-theory-an-anthology-pdf

Hoffman, E. T. A. (2018) “The Sandman.” Re-Image Publishing. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1939218/the-sandman-pdf

Hogg, J. (2013) The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner. Start Publishing LLC. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/784082/private-memoirs-and-confessions-of-a-justified-sinner-pdf

James, H. (2012) The Turn of the Screw. William Collins. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/670622/the-turn-of-the-screw-pdf

Jentsch, E. (2008) “On the Psychology of the Uncanny,” in Collins, J., and Jervis, J. (eds.) Uncanny Modernity: Cultural Theories, Modern Anxieties. Palgrave Macmillan. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3502684/uncanny-modernity-cultural-theories-modern-anxieties-pdf

Liggins, E. (2020) The Haunted House in Women’s Ghost Stories: Gender, Space and Modernity, 1850–1945. Palgrave Macmillan. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3481555/the-haunted-house-in-womens-ghost-stories-gender-space-and-modernity-18501945-pdf

Masschelein, A. (2012) The Unconcept: The Freudian Uncanny in Late-Twentieth-Century Theory. SUNY Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2673263/the-unconcept-the-freudian-uncanny-in-latetwentiethcentury-theory-pdf

Mori, M. (2012) “The Uncanny Valley.” IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine.

Punter, D. (2007) “The Uncanny,” in Spooner, C. and McEvoy, E. (eds.) The Routledge Companion to Gothic. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1606922/the-routledge-companion-to-gothic-pdf

Stevenson, R. L. (2019) Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Canongate Books. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1457578/strange-case-of-dr-jekyll-and-mr-hyde-shorter-scottish-fiction-pdf

Tinwell, A. (2014) The Uncanny Valley in Games and Animation. A K Peters/CRC Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1603212/the-uncanny-valley-in-games-and-animation-pdf

Weinstock, J. A. (2015) “Wondrous and Strange: The Matter of Twin Peaks,” in Weinstock, J. A., and Spooner, C. Return to Twin Peaks: New Approaches to Materiality, Theory, and Genre on Television. Palgrave Macmillan. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3508017/return-to-twin-peaks-new-approaches-to-materiality-theory-and-genre-on-television-pdf

Filmography and other media

Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within (2001) Directed by Hironobu Sakaguchi. Columbia Pictures. Available on Amazon Prime.

The Polar Express (2014) Directed by Robert Zemeckis. Warner Bros. Available on Now TV.

Us (2019) Directed by Jordan Peele. Universal Pictures.

Black Swan (2011) Directed by Darren Aronofsky. Available on Disney+.

Twin Peaks (1990–91) Created by Mark Frost and David Lynch. ABC. Available on Paramount+.

Detroit: Become Human (2018) Developed by Quantic Dream. Available on PlayStation 4 and Microsoft Windows.

Photography

“Hiroshi Ishiguro / Geminoid HI-4” (2016) Photographed by nrkbeta

“In Bed” (2005) by Ron Mueck at Fondation Cartier pour l'art contemporain, Paris. Photographed by Alexandre Van de Sande

“Untitled” (2010) by Sarah Lucas at the Museum of Cycladic Art. Photographed by Konstantinos Koukopoulos

PhD, English Literature (Lancaster University)

Sophie Raine has a PhD from Lancaster University. Her work focuses on penny dreadfuls and urban spaces. Her previous publications have been featured in VPFA (2019; 2022) and the Palgrave Handbook for Steam Age Gothic (2021) and her co-edited collection Penny Dreadfuls and the Gothic was released in 2023 with University of Wales Press.