The Labor Progress Handbook

Early Interventions to Prevent and Treat Dystocia

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Labor Progress Handbook

Early Interventions to Prevent and Treat Dystocia

About This Book

The third edition of The Labor Progress Handbook builds on the success of first two editions and remains an unparalleled resource on simple, non-invasive interventions to prevent or treat difficult labor. Retaining the hallmark features of previous editions, the book is replete with illustrations showing position, movements, and techniques and is logically organized to facilitate ease of use.

This edition includes two new chapters on third and fourth stage labor management and low-technology interventions, a complete analysis of directed versus spontaneous pushing, and additional information on massage techniques. The authors have updated references throughout, expertly weaving the highest level of evidence with years of experience in clinical practice.

The Labor Progress Handbook continues to be a must-have resource for those involved in all aspects of birth by providing practical instruction on low-cost, low-risk interventions to manage and treat dystocia.

Frequently asked questions

Information

- The powers (the uterine contractions)

- The passage (size, shape, and joint mobility of the pelvis and the stretch and resilience of the vaginal canal)

- The passenger (size and shape of fetal head, fetal presentation and position)

- The pain (and the woman’s ability to cope with it)

- The psyche (anxiety, emotional state of the woman).

- Environment (the feelings of physical and emotional safety generated by the setting and the people surrounding the woman)

- Ethnocultural factors (the degree of sensitivity and respect for the woman’s culture-based needs and preferences)

- Hospital or caregiver policies (how flexible, family- or woman-centered, how evidence based)

- Psychoemotional care (the priority given to nonmedical aspects of the childbirth experience)

- Progress may slow or stop for any of a number of reasons at any time in labor—prelabor, early labor, active labor, or during the second or third stage.

- The timing of the delay is an important consideration when establishing cause and selecting interventions.

- Sometimes several causal factors occur at one time.

- Caregivers and others are often able to enhance or maintain labor progress with simple nonsurgical, nonpharmacologic physical and psychological interventions. Such interventions have the following advantages:

- compared to most obstetric interventions for dystocia, they carry less risk of harm or undesirable side effects to mother or baby.

- they treat the woman as the key to the solution, not the key to the problem.

- they build or strengthen the cooperation between the woman, her support people (loved ones, doula [trained labor support provider]), and her caregivers.

- they reduce the need for riskier, costlier, more complex interventions.

- they may increase the woman’s emotional satisfaction with her experience of birth.

- The choice of solutions depends on the causal factors, if known, but trial and error is sometimes necessary when the cause is unclear. The greatest drawbacks are that the woman may not want to try these interventions; they sometimes take time; or they may not correct the problem.

- Time is usually an ally, not an enemy. With time, many problems in labor progress are resolved. In the absence of clear medical or psychological contraindications, patience, reassurance, and low or no risk interventions may constitute the most appropriate course of management.

- The caregiver may use the following to determine the cause of the problem(s):

- objective observations: woman’s vital signs; fetal heart rate patterns; fetal presentation, position, and size; cervical assessments; assessments of contraction strength, frequency, and duration; membrane status; and time

- subjective observations: woman’s affect, description of pain, level of fatigue, ability to cope with self-calming techniques.

- direct questions of the woman and collaboration with her in decisions regarding treatment:“What was going through your mind during that contraction?”“Please rate your pain during your previous contraction.”“Why do you think labor has slowed down?”“Which options for treatment do you prefer?”

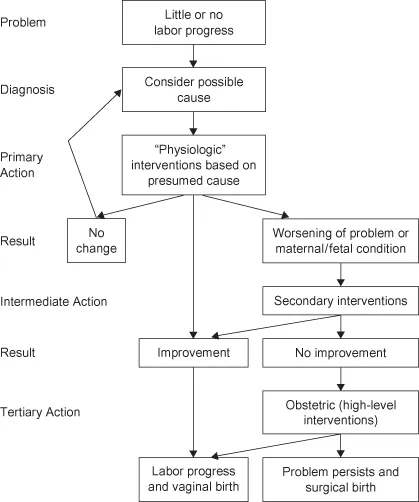

- Once the probable cause and the woman’s perceptions and views are determined, appropriate primary interventions are instituted and labor progress is further observed. The problem may be solved with no further interventions.

- If the primary interventions are medically contraindicated or if they are unsuccessful, then secondary, relatively low-technology interventions are used, and only if those are not successful are the tertiary, high-technology obstetric interventions instituted under the guidance of the doctor or midwife.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Foreword to the third edition

- Foreword to the second edition

- Foreword to the first edition

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Dysfunctional Labor: General Considerations

- Chapter 3 Assessing Progress in Labor

- Chapter 4 Prolonged Prelabor and Latent First Stage

- Chapter 5 Prolonged Active Phase of Labor

- Chapter 6 Prolonged Second Stage of Labor

- Chapter 7 Optimal Newborn Transition and Third and Fourth Stage Labor Management

- Chapter 8 Low-Technology Clinical Interventions to Promote Labor Progress

- Chapter 9 The Labor Progress Toolkit: Part 1. Maternal Positions and Movements

- Chapter 10 The Labor Progress Toolkit: Part 2. Comfort Measures

- Epidural Index

- Index