- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Psychiatry

About this book

Wondering what psychiatry is all about?

Want just the key facts?

Lecture Notes: Psychiatry provides essential, practical, and up-to-date information for students who are learning to conduct psychiatric interviews and assessments, understand the core psychiatric disorders, their aetiology and evidence-based treatment options.

It incorporates the latest NICE guidelines and systematic reviews, and includes coverage of the Mental Capacity Act and the new Mental Health Act. Featuring case studies throughout, it is perfect for clinical preparation with example questions to ask patients during clinical rotations.

Each chapter features bulleted key points, while the summary boxes and self-test MCQs ensure Lecture Notes: Psychiatry is the ideal resource, whether you are just beginning to develop psychiatric knowledge and skills or preparing for an end-of-year exam.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

- Psychiatry is part of medicine.

- Psychiatric knowledge, skills and attitudes are relevant to all doctors.

- Psychiatry should be as effective, pragmatic and evidence based as every other medical specialty.

- Psychiatry, like the rest of medicine, is becoming less hospital based. Most psychiatric problems are seen and treated in primary care, with many others handled in the general hospital. Only a minority are managed by specialist psychiatric services. So psychiatry should be learned and practised in these other settings too.

- Psychiatry is becoming more evidence based. Diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic decisions should, of course, be based on the best available evidence. It may come as a surprise to discover that current psychiatric interventions are as evidence based (and sometimes more so) as in other specialties.

- Psychiatry is becoming more neuroscience based. Developments in brain imaging and molecular genetics are beginning to make real progress in the neurobiological understanding of psychiatric disorders. These developments are expanding the knowledge base and range of skills which the next generation of doctors will need. These developments do not, however, make the other elements of psychiatry—psychology and sociology, for example—any less important, as we will see later.

- A basic knowledge of the common and the ‘classic’ psychiatric disorders.

- A working knowledge of psychiatric problems encountered in all medical settings.

- The ability to assess effectively someone with a ‘psychiatric problem’.

- Skills in the assessment of psychological aspects of medical conditions.

- A holistic or ‘biopsychosocial’ perspective from which to understand all illness.

- Make the patient feel comfortable enough to express their symptoms and feelings clearly.

- Use basic psychotherapeutic skills. For example, knowing how to help a distressed patient and how best to communicate bad news.

- Discuss and prescribe antidepressants and other common psychotropic drugs with confidence.

- Suffering is real even when there is no ‘test’to prove it.

- Psychological and social factors are relevant to all illnesses and can be scientifically studied.

- Much harm is done by negative attitudes towards patients with psychiatric diagnoses.

- Your own experience and personality will influence your relationship with patients—your positive attributes as well as your vulnerabilities and prejudices.

- It forms the main part of the psychiatric assessment by which diagnoses are made.

- It can be used therapeutically—in the psychotherapies the communication between patient and therapist is the currency of treatment (Chapter 7).

- To elicit the information needed to make a diagnosis, since a diagnosis provides the best available framework for making clinical decisions. This may seem obvious, but it hasn’t always been so in psychiatry.

- To understand the causes and context of the disorder.

- To form a therapeutic relationship with the patient.

- The interview provides a greater proportion of diagnostic information. Physical examination and laboratory investigations usually play a lesser, though occasionally crucial, role.

- The interview includes a detailed examination of the patient’s current thoughts, feelings, experiences and behaviour (the mental state examination) in addition to the standard questioning about the presenting complaint and past history (the psychiatric history).

- A greater wealth of background information about the person is collected (the context).

- This two-stage core and module approach considerably shortens most assessments—to 30–45 minutes or less. It also happens to be what psychiatrists actually do—as opposed to what they tell their students to do.

- There is an American alternative to ICD-10, called the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV), widely used in research. The two systems are broadly similar.

- Whatever the classification, remember the underused category of ‘no psychiatric disorder’.

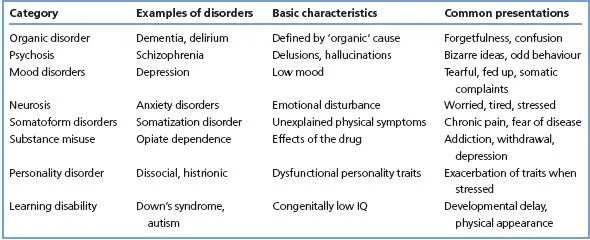

- A term such as ‘nervous breakdown’ has no useful psychiatric meaning—it may describe almost any of the categories in Table 1.1.

- Most diagnoses are syndromes, defined by combinations of symptoms, but some are based on aetiology or pathology. For example, depression can be caused by a brain tumour (diagnosis: organic mood disorder), or after bereavement (diagnosis: abnormal grief reaction) or without clear cause (diagnosis: depressive disorder). This combination of different sorts of category leads to some conceptual and practical difficulties, which will become apparent later.

- Comorbidity: many patients suffer from more than one psychiatric disorder (or a psychiatric disorder and a medical disorder). The comorbid disorders may or may not be causally related, and may or may not both require treatment. As a rule, comorbidity complicates management and worsens prognosis.

- Hierarchy: not all diagnoses carry equal weight. Traditionally, organic disorder trumps everything (i.e. if it is present, coexisting disorders are not diagnosed), and psychosis trumps neurosis. This principle is no longer applied consistently, partly because it is hard to reconcile with the frequency and clinical importance of comorbidity.

- Categories versus dimensions. The current system assumes there are distinctions between one disorder and another, and between disorder and health. However, such cut-offs are notoriously difficult to demonstrate, either aetiologically or clinically, whereas there is good evidence that there are continuums—for example, between bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, and for the occurrence of psychotic symptoms in ‘normal’ people. However, clinical practice requires ‘yes/no’ decisions to be made (e.g. as to what treatment to recommend) and so a categorical approach persists.

- Psychiatric classification is not an exact science. All classifications have drawbacks, and psychiatry has more than its share, as illustrated by the above points. Nevertheless, despite the imperfections, rational clinical practice requires a degree of order to be created, and most of the current diagnostic categories at least have good reliability, and utility in predicting treatment response and prognosis.

- Make a (differential) diagnosis, according to ICD10 categories (Appendix 1), using your knowledge of the key features of each psychiatric disorder.

- Attempt to understand how and why the disorder has arisen (Chapter 6).

- Develop a management plan, based on an awareness of the best available treatment (Chapter 7), how psychiatric services are organized (Chapter 8) and the patient’s characteristics, including their risk of harm to self or others (Chapter 4).

- Communicate your understanding of the case (Chapter 5).

- Psychiatry is a medical specialty. It mostly deals with conditions in which the symptoms and signs predominantly concern emotions, perception, thinking or memory. It also encompasses learning disability and the psychological aspects of the rest of medicine.

- Knowledge, skills and attitudes learned in psychiatry are relevant and valuable in all medical specialties.

- Be alert to the possibility of psychiatric disorder in all patients, and be able to recognize and elicit the key features.

- The major diagnostic categories are: neurosis, mood disorder, psychosis, organic disorder, substance misuse and personality disorder.

- To use the core and module strategy successfully you need a working knowledge of psychiatric disorders and their symptoms, in order to generate the diagnostic hypotheses that guide your assessment. This basic knowledge can be attained rapidly. A useful start is to learn Table 1.1 and to browse the key points at the end of Chapters 9–17.

- What is the time frame? Classically, the MSE is limit...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Getting started

- Chapter 2: The core psychiatric assessment

- Chapter 3: Psychiatric assessment modules

- Chapter 4: Risk: harm, self-harm and suicide

- Chapter 5: Completing and communicating the assessment

- Chapter 6: Aetiology

- Chapter 7: Treatment

- Chapter 8: Psychiatric services and specialties

- Chapter 9: Mood disorders

- Chapter 10: Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders

- Chapter 11: Eating, sleep and sexual disorders

- Chapter 12: Schizophrenia

- Chapter 13: Organic psychiatric disorders

- Chapter 14: Substance misuse

- Chapter 15: Personality disorders

- Chapter 16: Childhood disorders

- Chapter 17: Learning disability (mental retardation)

- Chapter 18: Psychiatry in other settings

- Multiple choice questions

- Answers to multiple choice questions

- Appendix 1: ICD-10 classification of psychiatric disorders

- Appendix 2: Keeping up to date and evidence based

- Further reading

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app