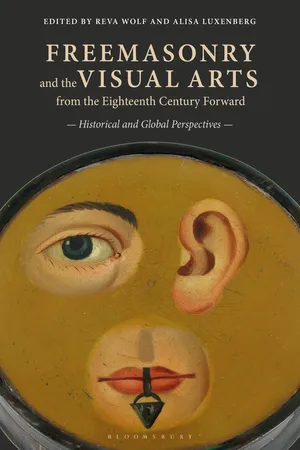

Freemasonry and the Visual Arts from the Eighteenth Century Forward

Historical and Global Perspectives

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Freemasonry and the Visual Arts from the Eighteenth Century Forward

Historical and Global Perspectives

About this book

Choice Outstanding Academic Title for 2020 With the dramatic rise of Freemasonry in the eighteenth century, art played a fundamental role in its practice, rhetoric, and global dissemination, while Freemasonry, in turn, directly influenced developments in art. This mutually enhancing relationship has only recently begun to receive its due. The vilification of Masons, and their own secretive practices, have hampered critical study and interpretation. As perceptions change, and as masonic archives and institutions begin opening to the public, the time is ripe for a fresh consideration of the interconnections between Freemasonry and the visual arts. This volume offers diverse approaches, and explores the challenges inherent to the subject, through a series of eye-opening case studies that reveal new dimensions of well-known artists such as Francisco de Goya and John Singleton Copley, and important collectors and entrepreneurs, including Arturo Alfonso Schomburg and Baron Taylor. Individual essays take readers to various countries within Europe and to America, Iran, India, and Haiti. The kinds of art analyzed are remarkably wide-ranging-porcelain, architecture, posters, prints, photography, painting, sculpture, metalwork, and more-and offer a clear picture of the international scope of the relationships between Freemasonry and art and their significance for the history of modern social life, politics, and spiritual practices. In examining this topic broadly yet deeply, Freemasonry and the Visual Arts sets a standard for serious study of the subject and suggests new avenues of investigation in this fascinating emerging field.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Freemasonry in Eighteenth-Century Portugal and the Architectural Projects of the Marquis of Pombal

The Symbolism of the Baixa

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The Mystery of Masonry Brought to Light

- 1 Freemasonry in Eighteenth-Century Portugal and the Architectural Projects of the Marquis of Pombal

- 2 The Order of the Pug and Meissen Porcelain: Myth and History

- 3 Goya and Freemasonry: Travels, Letters, Friends

- 4 Freemasonry’s “Living Stones” and the Boston Portraiture of John Singleton Copley

- 5 The Visual Arts of Freemasonry as Practiced “Within the Compass of Good Citizens” by Paul Revere

- 6 Building Codes for Masonic Viewers in Baron Taylor’s Voyages pittoresques et romantiques dans l’ancienne France

- 7 Freemasonry and the Architecture of the Persian Revival, 1843–1933

- 8 Solomon’s Temple in America: Masonic Architecture, Biblical Imagery, and Popular Culture, 1865–1930

- 9 Freemasonry and the Art Workers’ Guild: The Arts Lodge No. 2751, 1899–1935

- 10 Picturing Black Freemasons from Emancipation to the 1990s

- 11 Saint Jean Baptiste, Haitian Vodou, and the Masonic Imaginary

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

- Plate Section

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app