This is a test

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Taphonomic studies are a major methodological advance, the effects of which have been felt throughout archaeology. Zooarchaeologists and archaeobotanists were the first to realise how vital it was to study the entire process of how food enters the archaeological record, and taphonomy brought to a close the era when the study of animal bones and plant remains from archaeological sites were regarded mainly as environmental indicators. This volume is indicative of recent developments in taphonomic studies: hugely diverse research areas are being explored, many of which would have been totally unforeseeable only a quarter of a century ago.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Biosphere to Lithosphere by Terry O'Connor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. Some taphonomic investigations on reindeer (Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus) in West Greenland

Kerstin Pasda

In 1999 and 2000 an archaeological survey took place in the southeastern part of the Sisimiut-district in West Greenland (Fig.1.1: area 1 and 2). Research by wildlife biologists on reindeer in this region had been carried out recently (e.g. Thing 1984). Archaeological, ethnohistorical (Grønnow et al.1983) and archaeozoological (Meldgaard 1986) investigations supplement the picture. In this inland tundra with a mainly continental climate (Bøcher et al. 1980, 26, 44), the vegetation growth and cover is quite strong (Grønnow 1986, 67). Numerous remains of reindeer that died mostly of natural causes can be found in different stages of skeletal decay (e.g. Beyens 2000, 61; Vibe 1967, Fig.92, 93). The condition of the carcasses ranges from relatively fresh (still covered with skin and sinew) to completely defleshed and disarticulated skeletons, and isolated bones.

Throughout the survey 154 reindeer cadavers and about 670 single bones have been examined. For the determination of the biological age the methods of Hufthammer (1995) and Miller (1976) have been used. For sex determination, the shape and thickness of the ventro-medial wall of the acetabulum have been used visually; as in other artiodactyls, this part of the pelvis has diagnostic value (Boessneck et al. 1964, 89; Lemppenau 1964, 20). Various taphonomic aspects of those skeletons found in the tundra were examined:

a. their demography was compared to that of the living population,

b. the decomposition of reindeer cadavers in an arctic tundra,

c. the representation of skeletal parts in different locations (e.g. fox dens) and their comparison with archaeological sites,

d. carnivore gnawings and the pattern of bone fracturing.

The result of the examinations of reindeer skeletons in a recent arctic landscape contribute to the understanding of the development of bone accumulation in archaeological sites.

Demographic investigations

Thing (1984, 9–10; 1980a; 1980b, 151) describes today’s distribution of reindeer in their winter and summer habitat and their migration routes (Fig.1.1). Outside these areas reindeer are rare but present all year round. The major calving area (Fig.1.1: area 2) lies within the summer range. The summer range (Fig.1.1: S1) is occupied mainly from the first half of May until the first half of September. At the beginning of winter reindeer migrate usually within two or three weeks c. 50 – 70 km into their main winter habitat (Fig.1.1: W1). Little is known about the second summer habitat (Fig.1.1: S2) south of Kangerlussuaq. It is likely that in times of maximum population reindeer live here all year round. Only a part of them migrates into the main winter habitat (Meldgaard 1986, 21). A few animals migrate from the main summer habitat S1 into the second winter habitat W2 near the icecap.

Altogether, the sex and age of 154 complete carcasses, skeletons, and skeletal parts could be determined (Table 1.1). The spatial distribution of these carcasses show that the thanatocoenose in the examined area is a reflection of the seasonal activities of the living population: among the 79 subadult and adult carcasses 68% were females. The dominance of female skeletons is not surprising, as in living populations adult females usually predominate (e.g. Bergerud 1980, 565–566; Skogland 1985). The sex proportion is based on the different mortality of males and females. This begins at 3–4 years and increases with age to the disadvantage of the males. This sex proportion can also be seen in Pleistocene bone assemblages in Europe (Weinstock 2000, 57–58). Adult females die mostly around calving time or during lactation in late winter or early spring (Ringberg et al. 1980, 333–340; Thing and Clausen 1980, 434; Weinstock 2000, 57). This can be seen in the area under study (Table 1.1): All dead adult animals (n=22) within the radius of about 10 km around the calving area (Fig.1.1: area 2) are females. This confirms observations of spatial distribution of the living population (Thing 1984, 9). A seasonal determination of reindeer carcasses through the size and morphology of antlers was not possible, because nearly 60% of the females of this region are antlerless (Meldgaard 1986, 52–3). Remnants of skin on the carcases – consisting mainly of very long white hairs – suggests that death occured during winter. Those adult females that died in area 2 were probably weakened by pregnancy and birth. They probably died just before or after calving. The old age of most of the female carcasses – which can be inferred by the advanced wear of their teeth – may have contributed to this.

Figure 1.1: Central West Greenland (Sisimiut- and Maniitsoq-district), winter (W1, W2) and summer range (S1, S2) and migration routes (arrows) of reindeer (after Thing 1984, fig.3). Area 1: examined area in 1999 and 2000. Area 2: calving area in S1 as observed by wildlife biologists.

Comparatively many (29 of 54 or 54%) of the newborn calves and the few-weeks-old animals were found within and around the calving area (area 2; Table 1.1). In one case the remnants of a foetus were found in the abdomen of a rather old female. The percentage of very young animals in area 1 is at 33% comparatively low. The percentage of adolescent animals here, however, is, at 10%, higher than in area 2. Thing and Clausen (1980, 434) report that in the examined area in 1977 the death rate of 2–3-month-old calves was 50%. This high percentage results from calves’ illnesses such as infections, infestation of parasites or diarrhoea. These were often caused by the bad general condition of the mothers during pregnancy which led to the weakening and the susceptibility of the young animals (e.g. Espmark 1980, 495). Miller and Broughton (1974) documented in Canada that a huge percentage of the calves died because of bad weather conditions or because of being deserted by their mothers (see Skogland 1989, 55). Foxes and ravens are supposed to play an important role in the newborn reindeers’ deaths in Canada (Nowosad 1975, 207).

Decomposition of carcasses

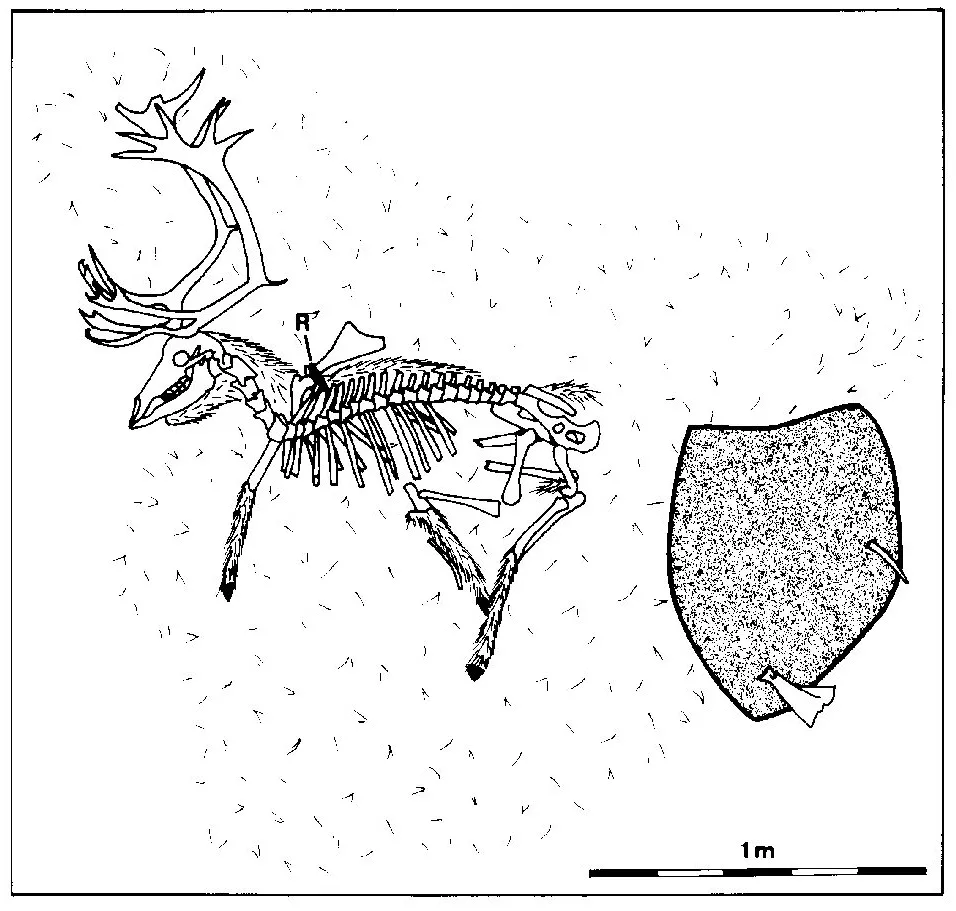

In the examined area twelve reindeer carcasses were drawn on a scale of 1:20 (e.g. see Fig. 1.2). A further skeleton was documented by photographs. Their geographical position was determined by GPS. Skeletons of different stages of decomposition and skeletal decay and of different ages were chosen for the documentation. They ranged from complete skeletons with sinews and remnants of skin to totally defleshed bones. All reindeer died a natural death. No typical location could be detected where remnants of reindeer lay: they were found on the banks of lakes, in the water, in valleys, on hills, under cliffs or on slopes. Big antlers, which rose above the low vegetation, could be spotted most easily. Sometimes skeletons could be seen through binoculars from elevated locations.

Table 1.1: Age and sex of documented reindeer carcasses in the study region.

area 1: summer range S1 and migration route to W1 (Fig. 1.1)

area 2: calving area in S1 (Fig. 1.1)

Figure 1.2: Nearly complete reindeer carcass with feather of a raven (R) between ribs and remains of hair (grey: boulder).

Four of the skeletons that had been drawn or photographed in the year 1999 had been revisited in the following year to observe their decomposition. Surprisingly, it turned out that their situation had changed very little after 12 months (Figs 1.3 and 1.4). The position of their bones and their disarticulation had progressed very little. The skin, sinews and maggots that had been observed the year before, were still present. However, Fig. 1.4 shows that the amount of skin was reduced compared with the year before (Fig. 1.3). The skin cover of the skull had decreased. The sinews on the vertebral spines had disappeared and the cover of sinews on the whole skeleton had decreased within the year. The left hind leg visible on the 1999 photograph was, one year later, still in articulation with the pelvis. The right hind leg was also still at the same position, though the amount of sk...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface: Peter Rowley-Conwy, Umberto Albarella and Keith Dobney

- Introduction: Terry O’Connor

- 1. Some taphonomic investigations on reindeer (Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus) in West Greenland: Kerstin Pasda

- 2. Magnitude of faunal accumulations by carnivores and humans in the South American Andes: Mariana Mondini

- 3. Anthropogenic versus non-anthropogenic bird bone assemblages: new criteria for their distinction: Véronique Laroulandie

- 4. Owls, diurnal raptors and humans: signatures on avian bones: Zbigniew Bochenski

- 5. Predator bias and fluctuating prey populations: Jim Williams

- 6. Taphonomic consequences of the use of bones as fuel. Experimental data and archaeological applications: Sandrine Costamagno, Isabelle Théry-Parisot, Jean-Philip Brugal and Raphaële Guibert

- 7. Taphonomic influences on cremation burial deposits: implications for interpretation: Fay Worley

- 8. Microfossils in Camelid dung: taphonomic considerations for the archaeological study of agriculture and pastoralism: M. Alejandra Korstanje

- 9. Why ancient DNA research needs taphomony: Eva-Maria Geigl

- 10. Bone density variation between similar animals and density variation in early life: implications for future taphonomic analysis: Robert Symmons

- 11. Contribution to knowledge of the Pleistocene mammal-bearing deposits of the territory of Siracusa (southeastern Sicily): Corrado Marziano and Salvatore Chilardi

- 12. Using comparative micromammal taphonomy to test palaeoecological hypotheses: ‘Ubeidiya, a Lower Pleistocene site in the Jordan Valley, Israel, as a case study: Miriam Belmaker

- 13. Fragments of information: preliminary taphonomic results from the Middle Palaeolithic breccia layers of Misliya Cave, Mount Carmel, Israel: Guy Bar-Oz, Mina Weinstein-Evron, Perry Livne and Yossi Zaidner

- 14. Bone weathering and food procurement strategies: assessing the reliability of our behavioural inferences: Nellie Phoca-Cosmetatou

- 15. Social changes in the early European Neolithic: a taphonomy perspective: Arkadiusz Marciniak