![]()

1

From Slavery to Middle-Class Respectability

Trust God—trust him for success, for support, for life. If in this way you will trust God, he by his word, by his Spirit and by his providence, will lead you into the highest usefulness of which, in your day and generation, you are capable.

John G. Fee, founder of Berea College, 1891

The year 1908 represented new beginnings for the Wheelers. On New Year’s Day, John Leonidas and Margaret Hervey Wheeler welcomed their second child into the world, a son they named John Hervey Wheeler. Across the country on that date, African Americans celebrated the annual Emancipation Day, gathering to rejoice in their freedom from enslavement and seeking full citizenship. In May, John Leonidas Wheeler resigned from his position as president of Kittrell College to take a job as an insurance agent with the North Carolina Mutual and Provident Association (later named North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company, or NC Mutual), the Durham enterprise founded a decade earlier. Both Wheelers had taught at Kittrell, a small college in Vance County, about thirty-seven miles north of Raleigh, from the time they arrived in North Carolina in 1898. Kittrell graduate John Moses Avery, a former student of John Leonidas and the company’s assistant manager, convinced him to join the NC Mutual family.1

“It was an inducement of making much money,” John Leonidas later explained. One generation removed from slavery, the Wheelers came to enjoy middle-class respectability through a post–Civil War vision of racial uplift alongside the hopes and aspirations of freedom rooted in educational attainment. The family’s transition from education to business, and their move to Durham, underscored the economic opportunities available in the city with its growing black community. The industrialization that had taken place there in the late nineteenth century was making Durham “the quintessential city of the New South.”2

Like John Leonidas, many black leaders delved into both education and business, and both black business and economic advancement are important for understanding black community development across the South. In the South in the 1890s, black business leaders had publicly articulated that the only path toward racial equality would be investments in black economic uplift. Shortly after the 1898 Wilmington Race Riot, NC Mutual president John Merrick asked, “What difference does it make to us who is elected[?] We got to serve in the same different capacities of life for a living.” In the first half of the twentieth century, many black business leaders hoped to achieve equality through expanding black enterprise. Early on, John Hervey came to appreciate the importance of economics to the overall plight of black people and to the New South more broadly.3

The NC Mutual had a profound impact on John Hervey’s early life in several ways. By 1912, the company promoted John Leonidas, and the Wheeler family moved to Atlanta. There, they regularly opened their home to company officials, including its founders, John Merrick and Dr. Aaron McDuffie Moore. The young boy would “listen carefully to the conversations” and observed: “Although he was a man of few words, Dr. Moore’s brain appeared to be a constant beehive of activity and his personality indicated a constant searching for truth and for new and better ways of doing things. For a youngster ten years old, these experiences left upon me a lasting impression of the all-inclusive manner in which Mr. Merrick and Dr. Moore worked so hard to place the company on a firm footing.” The two men, he said, “were in every sense of the word, social engineers, possessed with a oneness of purpose” and “exercised a strong influence upon my life as well as upon the lives of countless others.”4

John Hervey’s parents achieved economic success and middle-class respectability, which set them apart from the economic struggles of the black masses. They worked hard to place their children on a level playing field by building important community institutions and organizations. Nevertheless, their generation could not end Jim Crow segregation. John Hervey and his two sisters, Ruth and Margery, needed to carry their parents’ legacy forward to ensure they would have equality commensurate with their skill, potential, and intellect.5

“To Be Helped to Places of Usefulness and Respectability”

The Wheeler family came from Nicholasville, Kentucky, the seat of Jessamine County in the central part of the Bluegrass State. John Leonidas was born to Phoebe Wheeler on July 8, 1869, four years after the American Civil War ended. Phoebe and her parents, Lucius and Winnie Wheeler, had been slaves in Jessamine County, and her son joined “freedom’s first generation,” black people born during the war or to their ex-slave parents in the postwar era. During this adjustment period, blacks asserted their claims to full citizenship for the first time. John Leonidas’s father was white, reportedly his mother’s former owner, whose surname was Willis. Although John Leonidas never knew his white father, the family’s oral tradition held that he was a banker and one of Nicholasville’s leading citizens. The family selected the Wheeler surname upon emancipation.6

In 1863, the Union army established Camp Nelson in the county, and the military outpost soon became a symbol of freedom for enslaved Ken-tuckians. “Here,” writes historian Richard D. Sears, “the country’s newest citizens heard their first news about voting and citizenship and equality.” Margaret Hervey was another child born to ex-slaves in the Bluegrass Region. Born on April 12, 1877, at the end of Reconstruction, she was one of seven children born to John and Jennie Thomas Hervey. The senior Herveys may have been freed and bought farmland before the Civil War, though this is not documented. John Hervey estimated that his maternal grandparents owned about 150 acres where they grew tobacco and corn, putting them in a much better economic situation than most black families. Margaret Hervey took pride in having received her early education at a school that abolitionist John G. Fee built at Camp Nelson.7

Former slaves received emancipation in 1865, and once Reconstruction began, their hopes centered on education, land ownership, political rights, and control over their own labor. But only in February 1874 did the Kentucky state legislature finally establish a public school system for blacks. The new law unfairly taxed black Kentuckians, provided less state money for black education than white, and called for racially segregated schools. It also essentially withheld control over black education from black leaders, leaving white administrators to determine the direction of black education in the state.8

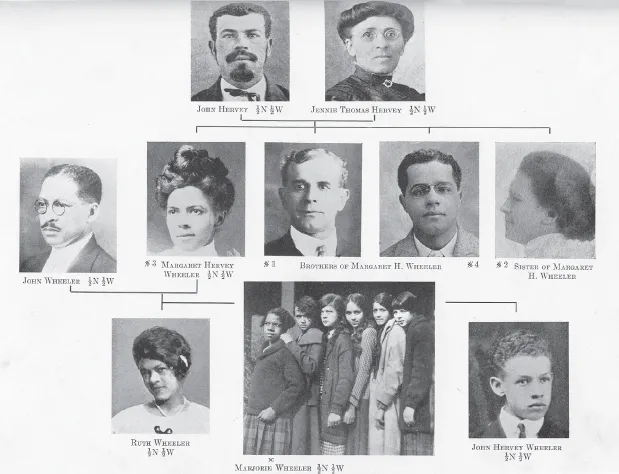

The Hervey-Wheeler family, showing the offspring of John and Jennie Thomas Hervey and their daughter Margaret Hervey, who married John Leonidas Wheeler on September 25, 1901. Their children, Ruth Hervey, John Hervey, and Margery Janice, are also pictured here. Three of Margaret’s siblings are included, two brothers and sister Ida Hervey (later Smith). Reprinted by permission from Caroline Bond Day and Earnest A. Hooton, A Study of Some Negro-White Families in the United States, Harvard African Studies, v. 10, Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University (Cambridge, Mass., 1932), plate 16.

Despite the challenges, John Leonidas attended public school, and he began teaching in Kentucky public schools in the late 1880s. Through determination and financial sacrifice, he saved up enough money to move to Xenia, Ohio, in 1889 and began attending Wilberforce University in 1890.9

Margaret Hervey also studied at Wilberforce, the AME Church’s flagship institution and the embodiment of black aspirations for freedom during the post–Civil War era. Founded in 1856, it was the premier hub for Christian liberal arts education for blacks. The school emphasized Christian values, piety, morality, and clean living, as well as the need for students to understand the extent to which they represented their race in everything they did. It is highly likely that John Leonidas and Margaret Hervey courted during their days at Wilberforce, and their courtship may have even had its origins in Kentucky, given that the two came from the same area. In college, they joined a rising postwar generation destined “to be helped to places of usefulness and respectability.” John Leonidas demonstrated a strong work ethic, paying his way by working in hotels and as a cook. A year after he enrolled, he received a scholarship that “was of great assistance to him.” Margaret Hervey’s training would have primarily centered on the domestic arts, while John Leonidas studied classics. One of his professors was W. E. B. Du Bois. Having graduated at the head of his class, John Leonidas received an invitation in December 1897 to chair the new classics department at Kittrell College in Kittrell, North Carolina. He accepted and moved there in 1898.10

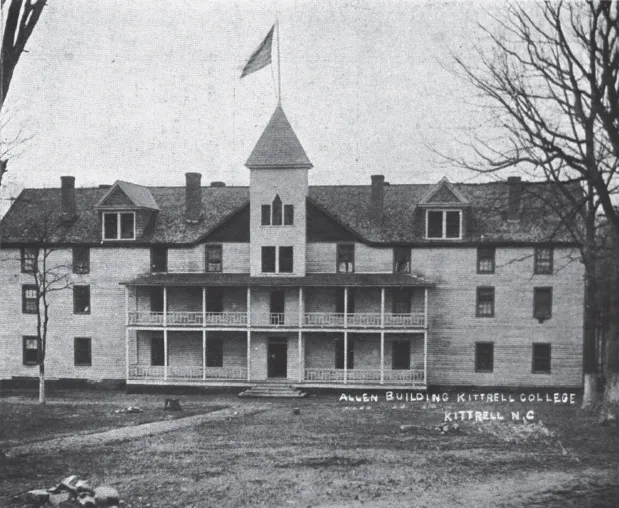

The Allen Building on the campus of Kittrell College housed the Industrial Department and doubled as a dormitory for male students until it burned to the ground on April 7, 1913. Reproduced from An Era of Progress and Promise, 1863–1910: The Religious, Moral, and Educational Development of the American Negro since His Emancipation, by William Newton Hartshorn (Boston: Priscilla, 1910). Courtesy of the State Library of North Carolina, Raleigh.

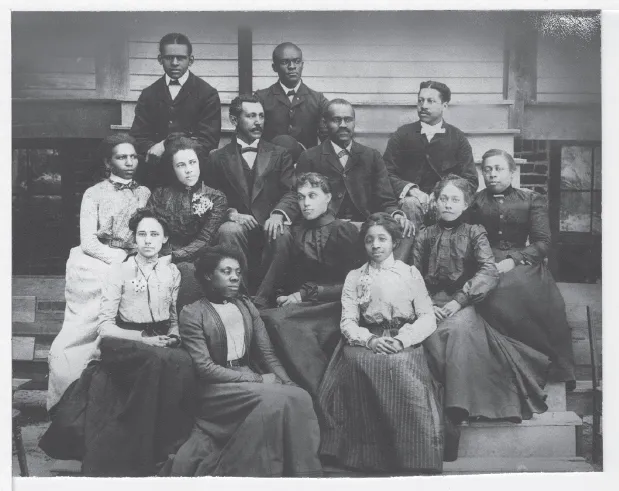

Kittrell College faculty. Men, left to right: Earle Finche, John R. Hawkins, George W. Adams (later M&F Bank cashier), Pinkney W. Dawkins, and John Leonidas Wheeler. The photograph’s original description includes the names of only five women, pictured here in no particular order: Mrs. John R. Hawkins, Kate Telfare, Mrs. Hawkins, Lena Cheek, and Rosa Alexander. Kittrell College Faculty, Scrapbook 2, undated, John H. Wheeler Collection, Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library.

Kittrell College began in 1858 as a resort, the Kittrell’s Springs Hotel, built exclusively for the use of wealthy white families. When the Civil War broke out, the Confederate army converted it into a Confederate general hospital. After the war, it briefly became a school for white women and then, again, a hotel. Just four days before the AME Church’s North Carolina Conference took possession of the site, a mysterious fire broke out, probably at the hands of an arsonist angered that the formerly all-white edifice would now be used to educate and uplift blacks. The fire left the two largest buildings in shambles. But the AME Church continued its plans and opened the school’s doors on February 7, 1886. A place built to serve whites and later used to protect the institution of slavery had become a place of black uplift and refuge, and its historical backdrop remained visible while the Wheelers lived at Kittrell.11

Margaret Hervey arrived after she graduated from Wilberforce in 1900, and the couple married in 1901. They would have expounded to their students the same principles they had learned at Wilberforce and through the AME Church. Kittrell’s annual reports and catalogues for this period reveal that the school’s primary objective was to foster in students “a spirit of self reliance and Christian manhood and womanhood.” In 1901, John Leonidas became president of what by that time was Kittrell College.12

“Planted on a Firm Basis”: The Industrial New South and the Rise of NC Mutual

By 1900, southern cities such as Durham, Atlanta, and Richmond had gained prominence because of industrialization in the latter half of the nineteenth century. In Durham, tobacco-manufacturing titans and other industrialists helped remake a region in shambles after the Civil War into what white southern newspaper editors deemed the “New South.” The idea described the South’s transition away from the “Old South” plantation society, which depended heavily on the slave economy. Southerners shifted gears to keep up with the North, which by that time outpaced the region industrially. The southern industrialists focused on the region’s economic advancement, which supposedly precluded racial antagonism, and the development of communities and towns around factories. These industrial centers, or New South cities, became known for manufactured goods that fueled economic growth, prosperity, and commerce.13

In the first thirty years after the war, Durham gained a reputation as an important and prosperous manufacturing town. At the center of its economic boom stood the tobacco industry, closely followed by cotton textile manufacturing, which helped place Durham on the map in relation to the regional, national, and global economies. The tobacco industry spurred development of financial institutions such as banks and insurance companies.14 The 1895 Hand-Book of Durham, North Carolina: A Brief and Accurate Description of a Prosperous and Growing Southern Manufacturing Town, a promotional publication implicitly for whites, described the city’s assets this way:

Durham has four lines of railroad; five tobacco factories, two of which are the largest in the world; four large cotton mills; four cigar factories; one fertilizer factory; one bag factory; one soap factory; two sash, door and blind factories; three banks; four tobacco warehouses for the sale of leaf tobacco; about 100 leaf tobacco brokers; two foundries; four machine shops; two carriage factories; four job painting offices; one book-bindery; one laundry; one marble yard; one cotton roller covering works; four insurance agencies; two daily papers; two weekly papers and two monthlies; four furniture stores; five drug stores; three hardware stores and about 100 other merchants representing various lines. Has twelve churches; one college; two graded schools and other industrial, educational and benevolent institutions.15

The list captured the mood of American industrial capitalism in the city, where world-renowned tobacco brands such as “Bull Durham” became synonymous with the Piedmont city. Black Durham’s rise, also spawned by industrialization, began before 1877, by which time the city’s largest black section was already referred to as “Hayti” (pronounced Hay-tī), a name ...