This is a test

- 222 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

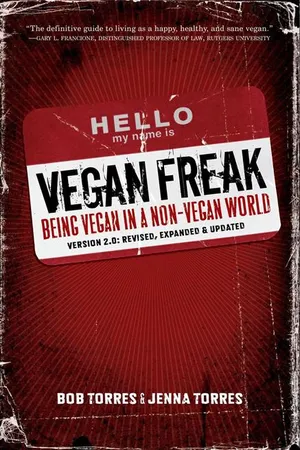

In this second edition of the informative and practical guide, two seasoned vegans help readers learn to love their inner freak. Loaded with tips, advice and stories, this book is the key to helping people thrive as a happy, healthy and sane vegan in a decidedly non-vegan world. Sometimes funny, sometimes irreverent and sometimes serious, this is a guide that's truly not afraid to tell it like it really is.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Vegan Freak - 2nd Edition by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Arts culinaires. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Arts culinairesCHAPTER 1

VEGAN AND FREAKY

“IF YOU’RE GOING TO LEAVE WITH ANYONE TODAY, I’D LIKE TO SEE YOU LEAVE WITH HER.”

The “her” in this case was Emmy, a then-eighteen-month-old medium-sized black shepherd mix, with a puffy, wild tail, and a calm but confident demeanor. She was, in every way that we could tell, a sweet and gentle dog, which is why what the director of the animal shelter told us came as a huge shock.

“She’s been here a year, and she really just needs to be in a loving home. Don’t get the wrong idea: she’s a wonderful dog—we love her! She’s friendly and house-trained, and great around cats. We just can’t seem to adopt her out because she is black.”

Naive as we were at the time, we’d not known about what’s called “Black Dog Syndrome,” the problem where black dogs are adopted at much lower rates because people have some kind of baseless fear about black dogs being more aggressive, or simply because black dogs don’t match their furnishings or something. Whatever the ridiculous reason, it was apparently why a dog as sweet as Emmy had been living in a shelter for a year. At any other shelter that euthanized animals, Emmy would have been killed within weeks; yet, when we arrived at the local no-kill shelter that day, she was every bit the confident, scrappy, and happy little mutt that we’ve come to know her as in the years we lived with her. Full of vigor, and really just ready to get out of her kennel at the pound, Emmy came home with us. We had the room and the resources, and we were only too happy to take in another dog. Emmy was going to be part of our family.

On the way home in the car, it didn’t take Emmy long to warm up to us. Almost immediately, she curled up on Jenna’s lap—quite a feat for a dog who weighs sixty pounds, but it can be done—and from that moment onward, it was as though Emmy had nominated us as her people. Our common bond with her has grown stronger and stronger everyday since, and like all of the other animals with whom we live, Emmy is part of our family. At breakfast every morning, Emmy curls up at our feet under the table, and we’ll occasionally slip her crust from our toast, or maybe a little chunk of banana, food that she always takes carefully and oh-so-gently, as if she might crush it if she weren’t careful. Every night, Emmy stretches out at the foot of our bed (probably because one of our cats often sleeps in her bed, but that’s another story). And every day when we write, Emmy is there to keep us company, with the nudge of a cold nose on the arm when our normal walk time rolls around.

It is probably clear by now, but we love Emmy dearly, just as we love our goofy, excitable, and playful lab Mole, our grass-munching, oversized eighteen-pound kitty Michi, and our two newest additions to the family, Spike and Taco, little kitten-brothers who came to us through a foster family. The little family of non-humans with whom we spend so much of our time has taught us a lot about what it means to be human, and what it means to love and be loved unconditionally. They’ve also taught us a lot about what it means to be non-human, and in doing so, they’ve helped us to overcome a lot of the hubris and pride that have colored our relations with animals in the past. In the years that we’ve been fortunate enough to share our lives with these non-human family members, we’ve come to know them to be as individual as any of us humans, if not more so. Long ago, we stopped thinking of them as “only animals” and have instead recognized how they simply possess a different set of skills and attributes than we humans do. Appreciating our animal family meant fully appreciating these differences.

As we began to evolve into this consciousness about the animals with whom we lived, we began to think critically and carefully about other animals, particularly the ones who died unnecessarily on a daily basis, only to end up on our plates as food. It doesn’t take a great logical or emotional leap to wonder if these billions upon billions of animals were every bit as desirous for companionship and freedom as the dogs and cats with whom we shared our lives. Having taken one of his bachelor’s degrees in agricultural science, Bob knew cows and pigs and chickens who responded by name, who recognized their “keepers,” and reacted excitedly when they came to visit. These same animals were obviously happy when they were with their families and saddened when separated from those they felt companionship with. If pigs, cattle, chickens, sheep, and other animals were so much like the animals so many of us live with, the question for us was a simple one: what made pigs, cattle, chickens, and sheep so different from dogs and cats such that we killed one for food and cuddled with another on the couch?

Once we were honest with ourselves, the answer was surprisingly simple: there really isn’t any difference that matters when it comes to the essential aspects of how we’d all like to be treated. In so far as all of those animals are sentient and have clear psychological, lasting, and subjective experiences of reality, their imprisonment, slaughter, and outright exploitation are no more just than the imprisonment, slaughter, or outright exploitation of our dogs, our cats, or even of any of us members of the human community. Being the well-socialized beings that we are, we all have little internal voices with answers at the ready for times like this. Like a good little cop for the existing order of things, the brain sounds the klaxons, puts up “DO NOT ENTER” signs, and spits back familiar yet comfortable responses. “Animals are ours to use.” “They were brought into existence to serve us.” “They’re not as smart as we are.” “They’re tasty.” “What would we eat if we didn’t eat animals?” “If I didn’t eat animal protein, I might die, or at least I’d look like some skinny-ass, pale vegan.” Unfortunately for the billions of animals a year that die for no other good reason than the fact that we humans like to eat them, these are the scripts that we all have in our heads about the way the world operates; these ideas not only reflect the current order of things, they also espouse a sense of how many of us believe things should be.

Veganism as a process and as a way of life is all about asking you to rewrite those internal scripts to recognize the inherent worth of animals. Coming to this awareness is complex and at times frustrating, making ethical veganism a complex gift. We’d be lying to you if we said it was easy to buck thousands of years of tradition and to deny the received social and cultural wisdom that says that doing things the same old way is just fine. Running against history is never easy, and there are times when it sucks. Yet, if we’re serious about justice and compassion, we must be serious about it for even what many would consider the least of us. In order to be consistent in our ideas of what constitutes equity, our notions of justice and compassion must expand outward to include non-human animals. As a vegan, or a soon-to-be-vegan, you will be at the forefront of this new and evolving cultural and social understanding. You will be the one who helps to right the thousands of years of wrongs. You will be the one who recognizes that the old way of doing things can’t be the way we continue to do things. You will be one of the many to stand up and say enough.

Our goal is to help you along on this journey. When we first heard about veganism, we thought it was a bit nuts, too. We weren’t sure that it was necessary, desirable, or even achievable, and we certainly weren’t sure that we wanted to bother with going much beyond regular old vegetarianism. We weren’t born into vegan families, and so we’ve come to this on our own terms. Though we have built up years of experience on the topic by teaching, writing, and speaking about it, we still clearly remember those first few fledgling weeks as proto-vegans, and we bring that awareness to what we’re doing here. With measured doses of humor, logic, advice, and tough love, we’ll help you to go vegan, or, if you’re already vegan, we are going to encourage you to think about veganism in new ways that will reinvigorate the passion that got you to go vegan in the first place.

Vej-uns, VAYguns, and Vegans Oh My

“But you don’t looooook like a VAY-gun.”

Oh? And what does a VAY-gun look like? And what the hell is a VAY-gun anyway?

We’ve both heard this particular refrain—we never can decide if it is a compliment or an insult—on more occasions than we care to count. Why can’t people just get the pronunciation right? We aren’t VAY-guns or VEEJ-uns, we’re vegans, you know, with a long “e,” like if you say the letter “v” and then add the word “gun” to it. Said correctly, the term “vegan” rhymes with the way a Canadian or American would say the name Tegan, as in half of the group Tegan and Sara. Vegan does not rhyme with “ray gun,” though “ray gun” is a fabulous way to say the last name of the 40th president of the United States, given his penchant for space weaponry and lasers and shit like that.

To get back to the idea of neither of us looking like vegans, we begin to honestly wonder: just what kinds of absurd stereotypes are people walking around with in their heads to get them to say such a ridiculous thing out loud? On the few occasions when either of us have asked people what they meant and people are honest enough to answer us, we usually we get some kind of combination of answers that draw almost fully on misconceptions about vegans. To most people who even know what a vegan is—admittedly, less of a problem now than when we did the first edition of this book—one of a few different stereotypes springs to mind. The most predominant misconception that we hear is that vegans are dreadlocked, stinky hippies, endlessly fascinated with hemp, hemp seeds, hemp milk, and/or marijuana. To most people who think of vegans as hippies, we’re clearly too busy chewing on granola and hanging out with the Rainbow Family in some national forest to really wrap our heads around how the world works. Some people think of vegans as impossibly skinny and malnourished, with yellow skin, thinning hair, and brittle nails because all we eat is tofu and apple juice. Yet others see vegans as judgmental, moralizing nut jobs who drive hybrid cars, endlessly lecture people on sustainability and “carbon footprints,” buy shoes made out of recycled tires, and refuse to eat anything that casts a shadow (Admittedly, this stereotype may actually have some truth to it). Neither of us really fit any of the above stereotypes, so people probably get confused, and end up telling us that we don’t look like VAY-guns. The thing is, there are actually vegan hippies (shocker, right?). There are also vegans who are malnourished because they subsist only on hummus, cupcakes, potato chips, and Coke. And there are obviously vegans who are judgmental assholes—actually there are plenty of them in our experience. But there are also vegan writers (including at least one Nobel Prize winner), vegan chefs, vegan firefighters, vegan people in the military, vegan moms and dads, vegan teachers, vegan congressmen, and probably even vegan ninjas and pirates (for the record: we think ninjas are cooler than pirates). There are vegans who are, without a doubt, insane, and vegans who are the very definition of sanity and composure. There are punk vegans and skinny PBR-drinking hipster vegans with fixed-gear bikes who wear chunky black glasses and Goth vegan vampires. There are vegans in Vienna and Venezuela. There are vegans who look like your mom and dad and your sister and brother. The point is that vegans come from all walks of life, from all ages, all genders (female, male, transgender, and otherwise), all sexual orientations, all body sizes, all races, all income levels, all political orientations (though really, we wonder about conservative vegans), and many nationalities. Of course, if you don’t actually know a vegan in real life, it is easy to let a stereotype constructed by the media give you all the details about how vegans look and act. Take it from the half of this dynamic writing duo with the Ph.D. in sociology: if nothing else, we humans are social creatures who value predictability, and that translates into us working most easily in generalities and their closely related cousin, the ever-dreaded stereotype. But as with all stereotypes, casting a single group under such a broad umbrella and making assumptions about people in that group is a troubling business, a business that is fraught with traps for the uninitiated and unfamiliar.

In this book, we need you to understand these stereotypes, because as you move more into veganism, you’re going to have to confront them head-on, whether you like it or not. Ideally, we’ll build a movement of people that is big enough, diverse enough, and vibrant enough so that we can begin to dismantle a bit of the wayward thinking about vegans, but in the meantime, you need to recognize that the stereotypes are out there. One of our primary goals is to give you some tools to deal with living with the ridiculous, unreal, and often bafflingly stupid expectations foisted upon you by unknowing friends, family, and others. It is like we vegans are some kind of exotic tribe that was recently discovered deep in the Amazonian jungle: people are unsure of what we eat, how we act, what we believe, and what we’re all about. We wish people would just chill out already; we’re not that foreign. We have the number zero; we understand how fire works; and we even have rudimentary technology. Granted, we are an odd and ragtag tribe that sometimes gets along and sometimes doesn’t, but what unites us as a tribe of ethical vegans is our shared belief that eating and using animal products is wrong—otherwise, we just wouldn’t be vegans. Just as people would probably misunderstand the habits and customs of the indigenous person from Amazonia regaled in feathers and face paint, they misunderstand our habits and customs and beliefs, too. So, regardless of how “normal” you are, in a world where consuming animal products is the norm, you’re always going to be seen as the freak if you obviously and clearly refuse to take part in an act of consumption that is central to our everyday lives, our cultures, and even our very own personal identities.

To correct a misunderstanding that many people had about the first edition of this book before having even bothered to read it, we don’t think that all vegans are freaks, and we don’t think you have to be a freak to be a vegan. However, it is patently clear that if you consciously separate yourself from others through everyday choices about food and other aspects of your life, you’re going to be viewed differently by those around you. This difference isn’t something you should run from. On the contrary, you should embrace this freakdom, be at home with it, and fully own it, not only for your own sanity, but also for the efficacy of building a vegan social movement as a whole. This ownership of your vegan freakdom is also the first and most critical step towards keeping you a happy vegan and building genuine vegan community. Whether you’re a new vegan or whether you’ve been a vegan for the last decade or more, recognizing this vital aspect of veganism is essential not only to your own long-term mental health but also to the long-term success of veganism as a community and movement of people who collectively decide say “enough already!” when it comes to the use and abuse of animals for human ends. It should go without saying that we wish being vegan were the most normal thing in the world, but at this point, we all should be honest with ourselves about the need to get more people to go vegan. As of this writing, there are more people in the United States who believe that they’ve had contact with extraterrestrials than there are people who are vegan.[1] This means that our approaches are only middling in their success, or the extraterrestrial biological entities are stepping things up in their plans for intergalactic domination, or, perhaps, both.

What Veganism Is

People are not only confused about what vegans look like—they’re confused about what veganism really is. A great deal of the blame for this can be laid at the feet of wishy-washy, non-committal people who like the label “vegan” for whatever reason but who nevertheless do obviously non-vegan things like eat cheese “on occasion,” or have meat “every once in a while.” Many of these same so-called “vegans” also eat cage-free eggs, or organic meats on occasion because they absurdly believe these products to be somehow “less cruel,” and somehow more acceptable. Let’s just get this out there now, right at the start of the book, Michael Pollan and his localvore meat-eating sycophants be damned: being vegan means avoiding animal products to the greatest extent possible, not because of some conception of personal purity, but because ethical vegans live their politics every single day as a form of protest against the use and abuse of animals for human ends. Veganism is our way of expressing our anger—yes, our anger!—with the injustice perpetuated through industries and practices that exploit animals. As vegans, we take the anger, channel it, and live in a way that, to the greatest extent possible, affirms the intrinsic worth of animals. Veganism is us living in the world the way we want the world to be, and denying the violence done in our names. Equivocating on the issues and simply failing to do what is right because it is more convenient does absolutely nothing to mitigate this violence. For each egg, a chicken suffers in unusually horrible confinement for hours and hours; the production of milk leads to the slaughter of tens of thousands of calves for veal every year in the US alone; and just about every other animal product we can think of leads to the death or suffering of someone who is probably at least as sentient as the dog or cat that you consider to be a family member. Conveniently obscured from the average consumer when they buy animal flesh, eggs, or milk at the grocery store, the suffering is still there, the hidden but ever-present ingredient in every animal product. While most everyone knows somewhere in the back of their brain that animals die for their food, most people fail to acknowledge it fully at either an intellectual or emotional level. For them, the psychological distance between their cheese or eggs or steak and the real, hideous, and sorrowful lives and deaths that animals experience is hidden behind euphemisms—“meat,” instead of flesh; “free range” instead of unfreedom—and cultural fairy tales about animals gamboling about in a rural paradise of verdant pastures. In this ideological cover-up that pervades our entire culture, people get to have their meat, dairy, and eggs and eat them too, all while someone else—most likely, an undocumented, under-aged, exploited worker[2]—does the dirty work to get those products to them. Animals also suffer lives of utter and total misery throughout the whole process, even in “organic,” “local,” “free-range,” and “humane” farming operations that are supposed to be somehow better. We don’t care what Whole Foods says: there is no humane animal product, period.

To be vegan is to have the guts to deny the fairy tale of the harmless animal product. To be vegan is to deny the psychological distance between the flesh in the Styrofoam tray at the supermarket and the someone—not the something—who that meat came from. To be vegan is to live fully and honestly with yourself about how animals are treated, and it is about your not taking place in that exploitative system to the greatest extent possible. Veganism is not only an affirmation about how we want the world to be, it is a lived form of protest, and our reminding people that everything is not quite right when it comes to how we treat animals. A form of everyday heroism in a world gone terribly wrong, veganism is your refusal to participate in a system that is ethically bankrupt. It is bravery in a time of cowardice.

For your refusal of this system to be sensible, it has to be complete. It cannot be something you do part time or once in a while and still have it make any ethical or logical sense. People are usually confused on this point, but think of it like this: if someone decides that breaking into people’s homes is a moral wrong, and they decide that in order to decrease the impact of their crimes, they’re only going to break into homes on Thursdays, are they still committing the moral wrong? The answer is obvious. While the thief may have reduced the extent of her thievery, she’s still violating the law—she’s just doing it less often. Similarly, if you decide that animals do not deserve to be used to produce food and clothing for you, and as a response, you eat meat only one day per week, you are still taking part in the perpetuation of a moral wrong, even if you can argue that you’ve reduced the extent of the harm. Reducing the consumption of animal products is nice and pro...

Table of contents

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- PREFACE TO VERSION 2.0

- VEGAN AND FREAKY

- BOB AND JENNA SOLVE THE NORTH KOREA PROBLEM

- HELL IS OTHER PEOPLE

- WHAT DO VEGANS EAT ANYWAY?

- IT’S NOT JUST ABOUT FOOD

- GO VEGAN, STAY VEGAN

- ABOUT TOFU HOUND PRESS

- ABOUT PM PRESS

- FRIENDS OF PM PRESS

- OTHER TITLES FROM TOFU HOUND PRESS

- INDEX