![]()

1

TRANSFORMING 14–18 EDUCATION

Kenneth Baker

When I became Secretary of State for Education in 1986, I was convinced that the key to raising education standards across the country was a national curriculum.

Traditionally, headteachers decided the curriculum. However, children of broadly similar abilities were achieving widely different standards from one part of the country to the next and indeed from one school to the next. I was sure that a national curriculum would narrow the gap. In addition, I agreed wholeheartedly with my predecessor as Minister of Education Rab Butler who said that all children should go through a ‘common mill’ of education in order to acquire a shared – one might say, connective – knowledge of the country and world they live in.

However, if I had the task of fashioning the National Curriculum today, I would limit its scope to children aged 5 to 14.

Children need a clear grasp of the English language so that they can understand and be understood. They need a good understanding of arithmetic, which they will use at home, at work and even in sport and leisure. They need an appreciation of physics, chemistry and biology – subjects which are fundamental to our understanding of the world around us. They need to know about the country they live in: our history, culture and traditions. They need to be able to place Britain in context by studying world geography, world history and the cultures and religions of the world, and by learning languages other than English. In addition, children need to find out how things are made, how to use tools and resources, like the internet, how to express themselves through dance, theatre, music and art, and to discover their strengths, and indeed their weaknesses, on the playing field.

These are the foundations for life, work and further learning. They represent the knowledge, skills and experiences which, in my view, schools should provide for children up to the age of 14.

When we introduced the National Curriculum, however, young people were required to continue to study ten prescribed subjects up to the age of 16. I now see this as too ambitious, for three main reasons: it made the school timetable extremely crowded; it required young people to study subjects which some found uninteresting and uninspiring; and it severely limited opportunities for practical, hands-on learning.

Subsequent secretaries of state took steps to ease the pressure on the 14–16 curriculum. Indeed, the Labour government introduced the notion of a 14–19 ‘phase’ of education and training. David Blunkett’s green paper ‘Schools: Building on Success’ said:

This led to the appointment of the Working Group for 14–19 Reform, chaired by my friend and colleague Sir Mike Tomlinson. The Tomlinson Report, 14–19 Curriculum and Qualifications Reform, published in 2004, was in my opinion one of the most important education reports received by the Labour government during its term of office. Its main recommendation was a fundamental reform of qualifications for 14–19-year-olds – in effect, the creation of a 14–19 curriculum. The report’s main conclusions were rejected and in its place, we saw the development of a suite of occupationally related Diplomas, which have failed to find more than a toe-hold in a small number of schools and colleges. Since then, however, the law has been changed to require young people to remain in education or training until they are 17 from 2013, rising to 18 in 2015. This change has all-party support.

This must be the time to create a new vision for 14–18 education. Like Professor Alan Smithers, I prefer 14–18 to 14–19, as it more accurately captures the four years of compulsory education or training from age 14.

However, two things hold us back:

•the exaggerated importance of transition from primary to secondary education at the age of 11; and

•our fixation with exams at 16 – especially the GCSE.

The evolution of secondary education in England

In the closing years of the nineteenth century, a series of Acts of Parliament required children to attend school and provided state funding for elementary education up to the age of 13. However, there was no statutory entitlement to state-funded education beyond this age and very few parents had the means to pay for their children to attend fee-paying grammar and public schools.

The Education Act 1902 established local education authorities and gave them the right to establish, maintain and fund secondary schools. This led inevitably to questions about what should be taught in these new secondary schools. The 1904 Secondary Regulations provided the answer: a general education comprising English language and literature, geography, history, a foreign language, mathematics, science, drawing, handicraft and physical training. The secondary curriculum was, in short, based very largely on the grammar and public school curriculum developed by Thomas Arnold and his followers during the nineteenth century.

The school leaving age was raised to 14 after the First World War, based on a belief that children needed more and better education to equip them for life in the modern world. In most cases, this meant staying on at an elementary school rather than transferring to a secondary school – which was the case for my own father who won a book prize at the age of 14 from his elementary school in Newport.

Some thought this unsatisfactory, and argued for a clearer definition of education for older children. Sir William Hadow was appointed to chair a consultative committee on ‘The Education of the Adolescent’, which reached this conclusion in 1926:

Relatively little progress had been made by the start of the Second World War, and the issue was revisited by the Educational Reconstruction Committee of the Board of Education in 1940–1.

There was general agreement that the school leaving age should be raised again, initially to 15, and that England should implement a tripartite system of post-primary education consisting of selective grammar schools, selective technical schools and modern schools.

There was, however, less agreement about the age at which children should transfer to these schools. The technical branch of the Board of Education favoured transfer at 13, but the secondary branch held out for selection at 11+, so as to keep intact what had become the standard five-year grammar school course for 11–16-year-olds.

The matter was settled by the permanent secretary in March 1941 ‘on the basis that the implementation of transfer at 13+ would take many years to achieve, whereas transfer at 11+ could be secured within five’ (Richardson and Wiborg, 2010, p. 6).

In short, this decision – which has had huge and lasting repercussions – was taken for essentially pragmatic reasons. In effect, the starting age for grammar schools settled the matter.

Age of transfer settled, the next question was how to allocate children to different types of secondary school. Educational psychologists claimed it was possible to use a battery of tests to establish the academic potential of all 11-year-olds. The 11+, as it came to be known, formed the basis for allocating children to grammar, technical and secondary modern schools after the 1944 Education Act.

Selective technical schools never really got off the ground. There were 317 in 1946 and while a few new ones were established in the years that followed, others closed or merged with neighbouring schools. In 1955, R. A. Butler commented upon the number of technical schools: ‘There are too few of these schools and too many of them are poked away in corners of technical colleges, and are failing to receive proper recognition and support’ (quoted in Edwards, 1960, p. 5). How right he was; but he was unable to arrest their decline. Quite frankly they were killed by snobbery – parents wanted their children to go to the school on the hill – the grammar – and not the one in town which they associated with greasy rags and dirty jobs.

At the same time, confidence in the 11+ started to diminish during the 1950s. A significant number of children in secondary modern schools turned out to be capable of passing O-levels, while a significant number of children in grammar schools turned out to be capable of failing them. This growing unease paved the way for the introduction of comprehensive education in most parts of England.

The policy of comprehensive secondary education started with Antony Crosland’s famous circular of 1965 which urged local education authorities to replace the tripartite system with a national system of comprehensive schools. Looking back, it seems extraordinary that such a fundamental change could be introduced without formal consultation or primary legislation, but so it was.

In the following years, over 1,000 grammar schools were abolished under Labour and Conservative governments. The education minister who signed the greatest number of death warrants was Margaret Thatcher – an episode in her career of which she did not like to be reminded.

The comprehensive movement, which had its roots in the thinking of socialists, like Professor Tawney in the 1920s, was based on the belief that the advantages of birth, wealth, privilege and social position available to some children could only be eliminated if all children, irrespective of ability and background, went to the same school in the same neighbourhood at the same time. This policy of common access was driven as much by social engineering as by any educational considerations.

Interestingly, the push for comprehensive education provided a brief moment when 11 ceased to be the only age of transfer in some parts of the country. Many local authorities had a significant number of small secondary schools. Expanding some while abandoning others would have been more expensive than adopting a new three-tier system of education, comprising first schools, middle schools and high schools.

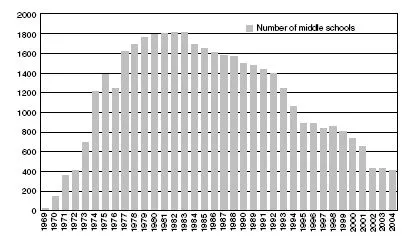

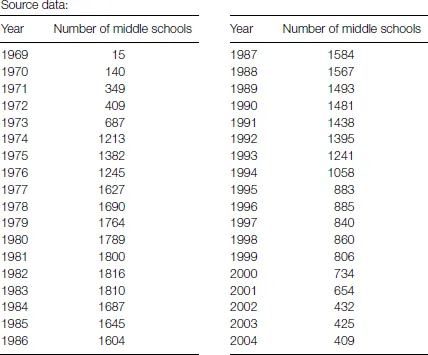

Middle schools typically catered for children aged 8–12 or 9–13. Legislation to permit transfer at ages other than 11 was passed in 1964, and the concept of the middle school gained further support in the 1967 Plowden Report, Children and Their Primary Schools (Department of Education and Science). At their peak, there were 1,800 middle schools in England and Wales, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Within a few years, however, local authorities started to abandon the three-tier system. The main reason was surplus capacity, caused by falling numbers of children of school age. The Audit Commission estimated that in 1990, there were 900,000 surplus places in English and Welsh primary schools, including many in middle schools straddling the primary/secondary divide (p. 5). It was said that eliminating these places would save £140 million a year. As a consequence, most local authorities followed the path of restoring two-tier education system. By 2011, 215 middle schools remained, spread across 19 local authority areas. It is safe to say that transfer at 11 again rules supreme.

Figure 1.1 Middle schools in England, 1969–2004.

Source: National Middle Schools Forum

The influence of exams at 16

The very existence of three-tier education in some parts of England – and in other countries, too, such as Germany and the United States – shows that there is nothing sacrosanct about transfer from primary to secondary education at the age of 11. As we have seen, however, many local authorities abandoned three-tier structures both to save money at a time of falling school rolls, and to align their structures with the system of Key Stages which I introduced over 25 years ago.

Looking back at what has happened since then, it is clear that Key Stage 3 (age 11–14) and Key Stage 4 (age 14–16) are now bracketed together in the minds of most children, teachers, parents and politicians: their shared purpose is to prepare children for GCSEs at 16.

This has skewed public, political and media perceptions of the aims of education. We have lost sight of the need to find and support the talents and ambitions of each young person and instead, we focus relentlessly on a single measure: the achievement of five GCSEs at grades A* to C, including English and maths.

It is little wonder that schools start to track pupils’ progress towards GCSEs from as early as Year 7; and while external tests (SATs) are no longer set for 14-year-olds, teachers have continued to assess each pupil’s progress in the following subjects at the end of Key Stage 3 (age 14):

•English

•Maths

•Science

•History

•Geography

•Modern foreign languages

•Design and technology

•Information and Communication Technology (ICT)

•Art and design

•Music

•Physical education

•Citizenship

•Religious education.

In 2004, David Blunkett introduced greater flexibility into the Key Stage 4 curriculum in order to accommodate the aptitudes, abilities and preferences of each student.

It is widely assumed that this flexibility resulted in a mass exodus from the traditional ...