Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of Marian apparitions, highlighting the features of the Zeitoun apparitions which are unique compared to other apparitions, as well as a discussion of the main explanations offered to interpret them. The chapter is divided into three sections. In the first section, a brief overview on the phenomenology of Marian apparitions is presented, which includes apparitions approved by Christian churches and categorizations of the visions of the Virgin Mary. In the second section, I review previous explanations and theories about the apparitions of the Virgin Mary. The focus will be limited to contributions of scholars who offered explanations from anthropological, historical, political, and psychological perspectives to the phenomenon of apparitions, with special focus on hypotheses which propose a relationship between the visions and their respective society. As we will see in this section, most scholarly investigations on Marian apparitions focus only on the social, historical, or “outer-world” events of the phenomenon, and they do not address psychological factors which may be at the root of these phenomena. Finally, in the third section, a review of Michael Carroll’s work on Marian apparitions from a psychoanalytic perspective is presented.

Overview on Marian apparitions

This section provides a brief historical overview of Marian apparitions, specifically focusing on reported apparitions in the last two centuries. In addition, it includes classifications of the types of Marian visions as well as those officially recognized by Christian churches (Catholic and/or Coptic).

Records on Marian apparitions and historical trends

The first known apparition of the Virgin Mary dates back to January 2 in A.D. 40 (Varghese 2000, p. 34). This apparition is described as a bilocation since Mary was still alive when she appeared to the Apostle St James in Caesaraugusta (present day Zaragoza), Spain. The apparition of the Virgin Mary instructed St James “to build a church under her patronage and name”, a theme which is repeated in other apparitions of the Virgin Mary throughout history (ibid., p. 34). Many of the apparitions which took place after the Apostolic Age were not documented, and reports of Marian apparitions in the first ten centuries of Christian history survived in three ways: 1) via popular shrines and pilgrimage sites that trace their origins to an apparition or vision; 2) personal accounts of the apparition from ecclesiastical authorities; and 3) accounts of Marian apparitions by the laity (Varghese 2000, pp. 34–35).

Church historians estimate that about 21,000 apparitional events have been reported throughout history (Bromley and Bobbitt 2011, p. 7; Horsfall 2000, p. 376). Pope Pius XII called the 1800s the century of Marian predilection, as many apparitions took place in France in that century, the most famous one arguably being represented by the Marian visions in 1858 of 14-year-old Bernadette Soubirious at Lourdes (Miller and Samples 1992). The popularity of the Virgin Mary in the 20th century is a result of the secret messages given to the visionaries at Fatima in 1917, which were in part made public later on in the 1940s (Horsfall 2000, p. 377); the messages received are an important source of inspiration for the network of divergent Marian devotion (Margry 2009, p. 246). There were two types of messages which distinguished 19th century apparitions from those taking place in the 20th century. For example, the La Salette (1846) messages reflected the conflicts surrounding the industrial revolution and modernity, while the Fatima messages were directed against the undermining of society, the ideology of socialism and communism, secularism in general, and “the deterioration of the Roman Catholic belief” such as birth control, abortion, homosexuality, etc. (Bromley and Bobbitt 2011, p. 9; Margry 2009, p. 246).

According to the Marian Library of the International Marian Research Institute (Dayton, Ohio; in Miracle Hunter), during the period from 1900 to 2009, 535 Marian apparitions have been recorded (512 of which are not officially recognized by the Catholic Church, i.e. on which no decision has been made or on which a negative decision has been taken by the Catholic Church). Interestingly, over the past two centuries, there has been an increase in the number of reported Marian apparitions throughout the world. Specifically, and according to the data taken from the Marian Library, there have been spikes in reported Marian apparitions in three time periods: the 1930s, the 1950s, and the period between the mid-1980s and the mid-1990s (see Figure 1.1). During the first two time periods, the 1930s and the 1950s, most of the reported Marian apparitions came from Europe, while in the more recent period mentioned recorded apparitions were more widespread geographically, increasing especially in countries in Central and South America, Asia, and North America, although Europe still maintained a significant percentage of reported Marian apparitions. A case by case

Figure 1.1 Marian apparitions from 1900 to 2009 by geographic area

analysis of the appearances in Figure 1.1 might suggest that some type of psychological disturbance had taken place in these countries at certain time periods, such as political instability in the Latin American world. Overall, beyond some periods which saw relatively high numbers of reported Marian apparitions, it is noticeable that the number of apparitions increased significantly from the 1930s onwards, being relatively low during the first three decades of the 20th century. One author on Marian apparitions places this great increase from 1945 onwards, particularly in the Western world, noting that the “frequency, content, structure…diverge from those of the preceding centuries” (Margry 2009, p. 245). I argue along the line that what lies behind the worldwide phenomena of Marian apparitions is a psychic disturbance caused by collective distress or anxiety. The connection between the phenomenology of Marian apparitions and collective distress is posited by many of the authors in the next section (Blackbourn 1993; Christian 1987; Ventresca 2003).

Apparitions recognized by the Christian churches (Catholic and/or Coptic)

Despite the thousands of apparitions that have been reported since A.D. 40, only a fraction of those have been recognized and approved by either the Catholic Church or the Coptic Church. An approved apparition may be explained as follows, “To accept an apparition or believe it to be authentic generally means…to judge it to be of divine origins, whereas to reject it or believe it to be inauthentic means to judge it to have a purely natural or perhaps even a demonic nature” (Zimdars-Swartz 1991, p. 11). Each claim is investigated by a local bishop or by a special commission appointed by him to interview visionaries and to study the situation (Horsfall 2000, p. 377). In the past, the local priests and bishops used aggressive interrogation methods in their investigations. The three children at Fatima were held and interrogated by priests; at La Salette, the young visionaries were called liars and threatened with imprisonment; in Marpingen, the seers were separated from their families and confined to the institution, kept under close observation and visitors were restricted (Bromley and Bobbitt 2011, p. 24). A negative decision may also be taken and this means that a proclamation cannot be made, pilgrimages are discouraged, and shrines are prevented from being established (Zimdars-Swartz, p. 10). Historically, there has been reluctance by the Roman Catholic Church to acknowledge Marian apparitions due, for example, to the contentious and political character of the messages from the visionaries creating a divergent Marian devotion; for example, visionary Ida Peerdeman received a message in 1951, following Pope Pius XII’s official proclamation of the Virgin’s bodily assumption into heaven, introducing the theme of Mary as Co-Redemptrix, a bone of contention within the Catholic Church for centuries (Margry 2009, pp. 245–246, 250). The Catholic Church was very cautious about its acknowledgement of the apparitions, and for the hundreds of reported visions in Italy in 1948, it did not give its stamp of approval to any of the apparitions; as Ventresca (2003) observes, the Church’s response was consistent with its centuries-old attitude towards the supernatural, with apparitions considered as a potential challenge to its authority in maintaining “a direct, immediate rapport between the Virgin Mary and the so-called ‘ordinary folk’” (Ventresca 2003, p. 446). Moreover, historically, the Christian church wrestled over the role Mary played in Jesus’s origin story, being aware that some of the titles that were applied to Mary were the same that were applied to her pagan forerunners; therefore, churchmen discouraged the laity’s adoration of Mary due to her strong ties to the Great Goddess (Walker 1983, pp. 602–603).

A majority of reported apparitions have not been investigated by diocesan commissions because they have simply failed to attract widespread public attention for very long and eventually they faded in memory (Zimdars-Swartz 1991, p. 10). According to Sandra L. Zimdars-Swartz (1991), out of hundreds of apparitions recorded in the last two centuries, seven have gained a particular widespread international attention, all of which have been recognized and approved by the Catholic Church: Rue du Bac (France, 1830), La Salette (France, 1846), Lourdes (France, 1858), Pontmain (France, 1870), Fatima (Portugal, 1917), Beauraing (Belgium, 1932–1933), and Banneux (Belgium, 1933). From this list, Lourdes and Fatima, most particularly, have been points of reference for investigations of later apparitions such as Marpingen in Germany, Ezquioga in Spain, Bayside in New York, and Clearwater in Florida, as we will see later. According to the list from the Marian Library, there are 33 fully approved apparitions and seven semi-approved apparitions. The Marian apparition at Zeitoun, Egypt was approved on May 4, 1968 by the Pope of the Coptic Orthodox Church and by Cardinal Stephanos, the patriarch of the Catholic Copts (Varghese 2000, p. 86). Official pronouncements or approvals of Marian visions are made by the Coptic Orthodox Church which occurred in a “Coptic Orthodox environment” since there is no “corporate unity” between Rome and the Coptic Orthodox Church (Johnston 1980, p. 14).

Seers of the apparitions of the Virgin Mary

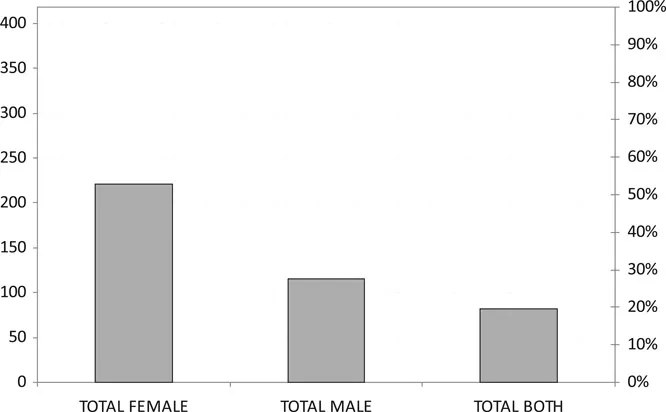

One of the features characterizing Marian apparitions is that most seers, or people who have witnessed apparitions, are female. Based on a list created by The Marian Library, I developed a chart showing the percentage of Female seers, Male seers, and Unspecified. In Unspecified, the gender of the seer or seers was not clear since the chart indicated words such as “3 children”, “several people”, and “1 religious person”, for instance. We can see from Figure 1.2 that out of 418 unapproved apparitions documented from 1900 to 2009, 52% of seers were female and 28% were male. Moreover, despite not being able to quantify them, it is clear from their list that a large portion of the seers were children.

Figure 1.2 Apparitions by gender (1900–2009)

The visions not only seem to appear more frequently to women and the young, but the seers are often described as lacking any exceptional quality and as “simple, naïve, sincere, and pious” (examples include Jeanne-Louise in Kerizinen, Bernadette in Lourdes, Rosa in San Damiano, and Melanie and Maximin in La Salette); moreover, the seers from early apparitional events were most often from poor and modest families with limited formal education and seers from the modern era “were described as leading conventional lives built around their roles as housewives and mothers” (Bromley and Bobbitt 2011, p. 12). A final interesting characteristic about the seers is that many of them were experiencing individual and family problems at the time of the visions. For instance, Mary Ann Van Hoof (Necedah) was bedridden due to serious illnesses. She survived an abusive first marriage, aborted a pregnancy, and experienced the death of an infant; Rosa (San Damiano) was also bedridden, had poor health, and was often in and out of hospitals; Louise (Kerizinen) suffered from chronic health problems throughout her childhood (Bromley and Bobbitt 2011, pp. 9–10).

Categorizations of Marian apparitions

William A. Christian Jr. (1981) examines apparitions in late medieval and Renaissance Spain, with particular attention to the regions of Catalonia and Castile. One of the interesting contributions made by Christian is his categorization of Marian apparitions. Christian traces the origins of Marian shrines in both of these regions and discusses a survey published in 1657 categorizing the legends associated with the shrines in Catalonia. In that survey, 14 legendary apparitions are documented. Christian categorizes two types of apparitions: “real” and “legendary”. Real apparitions are defined as those “stories for which there is no contemporary report”, while those in which there is documentation after the supposed event are labelled as legendary apparitions (Christian 1981, p. 7). For instance, just like there was a written documentation 800 years after Our Lady of Pilar in Zaragoza, likewise a legend can be found prior to the erection of a Marian shrine. Christian adds, “[s]uch legends were created to justify, illustrate, or dignify a preexisting devotion…[b]ut legends in turn can have a dramatic impact, and may even stimulate ‘real’ apparitions of an imitative nature” (Christian 1981, p. 7). The apparition at Zeitoun would be categorized as “legendary” as a 40-year-old legend is connected to the church in which the visions appear (see Chapter 6). Ruth Harris notes that some Marian shrines were founded on the basis of a miraculous apparition (Harris in Kselman 2001).

A more simplistic yet important categorization of apparitions can be found in Zimdars-Swartz (1991) where the more well-known apparitions of the last two centuries are examined. She focuses on six apparitions: three apparitions taking place before WWII (La Salette, Lourdes, and Fatima) and three which occurred after WWII (San Damiano, Garabandal, and Medjugorie). In her study, she concludes that much of the patterns in the pre-WWII apparitions could also be found in the post-WWII apparitions. The main theme emerging from both categories is Mary as the divine intermediator, an image prescribed to the Mary at Zeitoun (see third section and Chapter 6).

Interpretations and explanations

This section reviews previous explanations and interpretations offered on the apparitions of the Virgin Mary. There is a wealth of scholarly work (in addition to the not so scholarly work) on visions of the Virgin Mary and the Marian cult. For the purpose of the present study, I think it is particularly interesting to focus on the works relating to the phenomenology of Marian apparitions which address the historical, socio-political, religious, and economic component of the visions. This section is divided into two parts: the first part introduces socio-political and religious explanations for Marian apparitions, while the second part, albeit not directly addressing approaches to interpret the visions, examines associations of post-WWII Marian apparitions with apocalyptic themes.

Socio-political and religious interpretations

One of the most fascinating works on Marian apparitions was carried out by the historian David Blackbourn (1993), standing out for his careful and laborious investigation of the material relating to the Marpingen phenomena, especially in his usage of archival material and economic data. Blackbourn investigated Marian apparitions that took place in Marpingen, Germany, in 1876, when three children, all 8-year-olds, saw a woman in white while picking blueberries. During this period, the village of Marpingen was facing religious persecution by the Prussian state as well as suffering from “the effects of severe agricultural and industrial recession” (Blackbourn 1993, p. 91). Following an industrial and economic boom in 1873, the new German Empire’s economy crashed and fell into a Great Depression (Blackbourn 1993, p. 91). Religious persecution took on the form of the Kulturkampf or the culture-clash/culture-war which consisted of legislative measures that passed between 1871 and 1876 as part of a “preventive” strategy against the Catholic minority in Prussia. The Protestant Prussian state co-opted the liberal anticlerical in order to help pass laws such as the “May Law” of 1873 which allowed state control over education and appointment of the clergy. According to Black-bourn, “The great state-building process of the nineteenth century Europe, whether it took place within a monarchical, imperial, or republican form, challenged the authority and jurisdiction of the church” (Blackbourn 1993, p. 27). The apparitions of the 1860s and early 1870s were cases that shadowed political upheaval with the creation of new states redrawi...