![]()

1

Small Fish in a Big Pond

SME and Innovation in BRICS Countries

Ana Arroio and Mario Scerri

It is not by a slip that an inverted popular quotation was permitted to intrude into the title of this section. The analogy is useful because it brings to mind an image of numerous, dispersed and heterogeneous ‘small fish’ swimming confusedly in an oversized, inadequate and dangerous ‘pond’ and this corresponds to the experience faced by millions of micro and small firms spread throughout the developing world. It illustrates an often confusing and challenging reality. Nonetheless, understanding and working with this reality is essential as small firms are central to capitalist development; they are thought to have the capacity to change the world both through the generation of critical income and also through their role in the Schumpeterian cyclical ‘waves’ that are the key drivers of innovation, thus furnishing the potential for great social and economic transformation.

This is a powerful proposition that lies at the heart of the rationale for this book. There is an important parallel in the development of new (usually small and medium) businesses and new forms of innovation, production and commercialisation of goods and services. These firms have the potential and flexibility required to capitalise on emerging technological and other opportunities for growth, as well as the fact that they do not offer the usual resistance to their incorporation, mainly because they are not tied down by patterns that are being superseded. Second, the challenge faced by most countries in achieving economic growth, difficulties that increased significantly in the transition to the millennium, intensified the search for the means to strengthen the economic tissue and generate employment and income, particularly through the promotion of the creation and development of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). Third, the increase in economic and social inequalities between countries and regions, both more and less developed, has shifted the policy focus towards the promotion of less-favoured regions, including the promotion of the small firms that in many cases comprise the basis of local economies (Lemos et al. 2003).

Buffeted by strong currents, these firms struggle to survive in a highly challenging, mostly adverse, global scenario. ‘Globalisation’ heralds the promise that the pond will get bigger; however, in many cases this apparently larger potential is an illusion, or available to the very few, and in other instances, the fish are becoming noticeably smaller. The analogy highlights the urgency of a new approach to understanding the opportunities and challenges to the sustainable development of small and medium firms, an urgency that is heightened by the crisis and conflicts that characterise the globally competitive accumulation regime. The aim of this volume is to address some of the challenges to the sustained growth of small firms looking at the development alternatives that are evolving in Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS).

The authors use a broad national system of innovation (NSI) approach as a theoretical framework. According to this perspective, the effectiveness of policies for the promotion of SMEs depends on a wide-range set of factors that include the historic specificity of each country and the existing macroeconomic and social contexts, business and institutional environment and related policies. Besides drawing out the importance of the NSI concept for an analysis of SME policies, this introductory chapter offers an analysis of the varieties of the NSI concept that have been adopted by BRICS to deal with the policy challenges of strengthening small and medium firms. The next section provides a general picture of the environment for SMEs, pointing out their relative importance and strength in BRICS, and this is followed by a discussion that highlights relevant dimensions of the individual realities of the five country cases that are dealt with in more detail in Chapters 2–6. This chapter concludes with policy implications and foundations for future research in this area.

The Importance of the System of Innovation Framework for SME Policy and Varieties of the Concept in BRICS

Systems of innovation, understood as a set of differing institutions that contribute to the development of the learning and innovation capacity of a country, region, economic sector, or locality, and which comprise a series of elements and relations that link together the production, assimilation, use, and diffusion of knowledge, have been defined, studied and adopted as an important analytical tool and framework to guide analysis in both developed and underdeveloped countries (Cassiolato and Lastres 2009; Freeman 1982; Lundvall 1988). The framework takes into account the specific social, economic and political realities of each country, the local or tacit nature of knowledge and innovation, and also the power relations in discussing innovation and knowledge accumulation. The relevance of the NSI framework for BRICS has been extensively discussed in J. E. Cassiolato and H. M. M. Lastres (2009).

It is argued here that the NSI concept can be usefully employed to focus on the processes of interaction, co-operation, learning, and development of capabilities in small and medium firms. The concept enables taking into account the micro-, meso- and macroeconomic dimensions that are central to innovation efforts and allows focusing on issues and dimensions that are not usually considered including the productive, financial, social, institutional, and political spheres. Most importantly, for the innovation system of BRICS countries and SMEs, the NSI approach provides lenses that can be used to examine learning processes; historical and cultural trajectories; and social, regional, gender, and other inequalities.

While NSI researchers concur that national and local conditions may lead to completely different paths and that there is not only one solution and policy prescription but rather a myriad of alternatives, it is nonetheless possible to draw several lessons from the experiences presented in this book. Importantly, the adoption of a common theoretical framework allows research to draw back, analyse the bigger picture and draw lessons which can be of value to the broader discussion on the role of innovation in socioeconomic development.

Varieties of the NSI concept in BRICS

Reflecting an international move towards recognising the need to develop a systemic approach to the promotion of innovation and competitiveness of firms and individual agents, polices have focused more clearly on clusters of firms (Freeman 1987; Piore and Sabel 1984; Storper 1997). In particular, policies to promote technological and industrial development increasingly recognise that the agglomeration of enterprises and the best use of the collective advantages generated by their interactions, and also by their exchanges with the surrounding environment, can effectively contribute to the strengthening of their chances of survival and growth, and represent an effective source for sustainable competitive advantages (Cassiolato et al. 2003). This approach suggests that collective learning processes, co-operation and dynamics of groups of firms are fundamental to meeting the challenges of economic, social, technological, and knowledge asymmetries. Gradually, existing programmes have begun to provide support to groups of small firms, employing varying conceptual definitions and terminologies, such as firm networks; technological parks; incubators; co-operative projects; clusters; productive, regional, sectoral, or export zones, among others (Piore and Sabel 1984; Porter 1998; Storper 1997).

A unique experience in public policy to foster collective regional entrepreneurship and SME innovation is the Local Productive Systems (LPS) approach examined by Ana Arroio in the chapter on Brazil. This concept is grounded in the NSI perspective to guide economic, industrial and social policies that seek to strengthen the interactions among SMEs and to promote learning and innovative capabilities. LPS represent a practical unit of analysis and investigation that goes well beyond traditional views based on individual organisations (enterprise) or economic sectors, comprising both the territorial dimension and economic activities. This approach expands the sectoral system of innovation perspective not only because it brings to the fore the heterogeneous agents (enterprise and research and development [R&D] organisations, education, training, financial agents, etc.) and related activities that are necessarily comprised in any productive system but it also highlights the conditions under which local learning, the accumulation of productive and innovation capabilities and effective use of these capacities occur. For developing countries this is absolutely vital.

Although other BRICS countries have not articulated SME policy making in terms of such a conceptually structured NSI approach, the need to bridge the gap between the challenges of globalisation, development and innovation-based competitiveness has meant that all countries have to some extent found a response in the systems of innovation approach. In South Africa, the systems of innovation framework has been used to organise public resources in research, development science and technology since 1996 when the publication of the White Paper on Science and Technology established the parameters and orientation of the reframed NSI. The South African policy framework is particularly relevant for analysis of strategies to strengthen SMEs considering that in the post-apartheid policy framework, these firms are perceived to occupy a central role in the achievement of social (poverty alleviation), economic (employment creation, growth) and political (black economic empowerment) objectives.

China also adopts an explicit NSI approach, and the evolution of its approach to scientific and technological policy making described by Yuan Cheng and Jian Gao illustrates key milestones in the development stages associated with strengthening the innovation system. In the current phase, beginning from 1998, the country has focused on enhancing the innovation capabilities of domestic enterprises, including the technological capabilities of SMEs.

Both the India and Russia country studies provide a detailed description and analysis of legislation and policy instruments to support SMEs, giving a comprehensive overview of the role of SMEs in the country’s system of innovation. In the chapter on India the focus is on the huge policy challenges inherent in an innovation system torn between highly competitive SMEs that display technological capacity and vibrancy on one hand, and the profusion of tiny, small sector firms, often grouped in what has been termed ‘poverty clusters’, on the other hand. They show that increased competition from the world market has led to increasing concentration of SMEs in more advanced regions, thus aggravating rather than mitigating regional inequities. The chapter on Russia examines the consequences of immersion in the global economy without an adequate legal and institutional framework to shield the development of SME. In both these countries, policy making in general, and for SMEs in particular, is not couched explicitly in an NSI perspective.

Almost all of the chapters highlight the need for more detailed analysis using both regional and sectoral innovation systems perspectives. The authors in this book make it clear that it is important to tailor the NSI concept to study in more focused detail the regional and sectoral specificities that may lead to improved policy making for a broader spectrum of SMEs. This is because regional-level-specific mechanisms for supporting small- and medium-size entrepreneurship are considered crucial to their sustainable development. The Brazilian experience that looks at LPS can bring important insights for such studies, and these are drawn out in the final section in this chapter.

Setting the Stage: The Role of SMEs in BRICS

This section brings to the fore central aspects of the social and economic context, in addition to the business environment, that are essential to analyse SME development and that are summarised in Tables 1.1 and 1.2. The data reveal that SMEs play an important role in BRICS economies, representing in most cases over 90 per cent of total firms. Although studies show that these firms are less important in terms of wage generation, as salaries are significantly larger in bigger firms, SMEs provide a much needed cushion to absorb the labour force contingent, particularly in China and India. They also provide a buffer to high unemployment rates, such as those registered in South Africa, reaching 23 per cent or even higher when capturing those who have given up registering for work.

These firms must deal with a highly challenging financial and business environment. Although all BRICS have managed to achieve positive Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth in the new millennium despite an adverse international economic scenario, short-term interest rates are high in most countries, and very high in Brazil and India; this is compounded by the fact that official credit-lines for SMEs are in most cases practically non-existent, and even when formally in place, very difficult to access. In terms of inflation, the scenario in most countries has improved significantly from the late 1980s and early 1990s when extremely high inflation rates were feeding the financial economy rather than the ‘real economy’. Nonetheless, existing rates of over 5 per cent in most cases may prove too steep for the survival of many SMEs.

Table 1.1 SME in BRICS Countries: Social and Economic Context, 2012

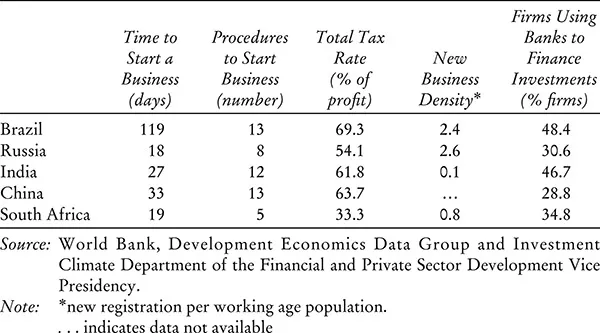

Table 1.2 SME in BRICS Countries: Business Environment, 2012

The business environment is equally challenging. Opening a formal business enterprise in Brazil is not for those that are in a hurry, as this could take as long as 120 business days (see Table 1.2). The tax rate is high in all countries and absorbs a significant percentage of profits, reaching 69 per cent in Brazil. Russia is the champion in terms of new business density and, together with South Africa, is one of the countries that require the smallest number of procedures to start a business, and likewise these two countries can boast of the smallest interval to start a business. The last column in Table 1.2 — ‘Firms Using Banks to Finance Investments’ — shows that a significant proportion of formal SME business enterprises benefit from investment financing, reaching almost 50 per cent in Brazil and India. It is important to keep in mind that these figures do not comprise informal business indicators.

However, a comparison of World Bank Business Environment indicators between 2007 and 2009 reveals dramatic changes in the data. The main point is that it has become much easier to start a business in almost all BRICS countries, both in terms of the time to start a business and the number of procedures that are required. This holds true for all countries except Russia, where both indicators have increased in the two-year period. Most importantly, the percentage of ‘firms using banks to finance investments’ has gone up dramatically: it has more than doubled in Brazil (from 22.9 per cent to 48.4 per cent, an increase of 110 per cent) and India (from 19.4 per cent to 46.7 per cent, a growth of 141 per cent), almost tripled in China (from 9.8 per cent to 28.8 per cent, a 194 per cent increase) and over three-fold in Russia (from 10.2 per cent to 30.6 per cent, up by 200 per cent). Taken together, changes in these indicators confirm that public policies can have an important impact on business practices and must be carefully conceived and tailored to the environment faced by SMEs.

These countries have several aspects in common that may have a profound impact on how policies for SME are conceived, developed and implemented. These include demographic and social aspects, such as the high degrees of inequality in the distribution of income; their large, or extremely large, population densities; and associated challenges in the provision of essential goods and services, including water, food, energy, sanitation, education, and health. Additional development challenges such as relatively large unemployment figures, the significant gap between the rural and urban populations, the immense regional disparities in human and economic development, and perverse regional income distribution patterns are common themes that justify focused attention on policies for SMEs.

As regards economic and productive structures, BRICS have the importance of agricultural and extractive activities as well as the transformation of mineral and energy resources in common. The magnitude of their agro-industry and the rich biodiversity are noteworthy and may offer important windows of opportunities for SME policies.

The trends and directions of SME policies will also be to a large extent dictated by the different strategies for development that have been adopted in BRICS and their various degrees and forms of integration into the world economy. Thus in Russia, specialisation in petroleum, the gas complex and other natural resources associated with the strength and impact of the 4,000 research institutes inherited from the Soviet era has led to strong policies within specific industrial clusters, as discussed in Alexander Sokolov and Pavel Rudnik’s chapter (Chapter 3). The opportunities and challenges associated with the various development strategies are drawn out in individual country chapters.

BRICS have faced intense political and economic transformation processes in the last decades. They have dealt in diverse manners with the impacts of liberalisation, deregulation and financial instability. The significant increase in their participation in international trade, fostered by the Chinese and commodity booms, has led to specific vulnerabilities in SMEs dedicated to the export sector or that are attempting a more nuanced insertion in global production chains, as addressed particularly in the analysis of the role of SMEs in national innovation systems in the chapters on China and India.

Russia and Sou...