Preliminary remarks

I concede that this is a strange title. Berger and Luckmann are obviously Austrians, if one considers the location of their birth,1 or they may be at least considered quasi-Austrians. Beyond the triviality of the birth certificates, Peter Berger puts Michaela Pfadenhauer in mind of a typical Austrian “coffee shop intellectual” (Kaffeehausintellektueller) who has a certain affinity to luxurious urbanism: Whereas Thomas Luckmann represents, in her words, the Austrian contrary type, with his affinity to nature and enthusiasm for fishing, Berger represents the “Austrian-Slovenian Alpine eremite” (Pfadenhauer 2010: 16). In another context, Luckmann has speculated about Berger’s and his own common Kakanian roots, and in his autobiography, Berger remembers various speculations, together with Luckmann, about what the content of their advisory opinion would have been had they been asked which political measures they deemed necessary in order to maintain the Habsburg Empire in 1910. Therefore, both seem to show at least mental traces of Austro-Kakanian origin and affinities to historic Austria. But, as one might suppose, this is not the mainstay of my considerations.

Let us turn to the intellectual background. Sharing the basic assumption that social constructivism is, in fact, a paradigm, I will try to explore the origins of both Berger’s and Luckmann’s theories in the intellectual climate of interwar Vienna (via the intermediation of Alfred Schütz). I will not constrain the intellectual history to the well-known Weber-Husserl-Bergson-Schütz-Berger-Luckmann story. Rather, I will try to give a short survey of a more extended intellectual map: a landscape of theoretical discussions, distant or close paradigms, common questions and divergent answers.2

My central point will be the Austrian part of the story. The work developed by Alfred Schütz (1899–1959) is an answer to the dominant questions discussed intensively in Vienna in the interwar period, the last phase of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Schütz (in Husserl’s words, a banking executive by day and a phenomenologist by night) was present during all of these exceptional discussions, circles and meetings. Berger and Luckmann further developed Schützian work: They elaborated his ideas, added considerations originating from American pragmatism, and they provided a more sophisticated version of the process of institutionalization. Above all, they made Schütz understandable.

The first important step was the continuation and propagation of Schütz’s ideas by Berger and Luckmann, made very much more readable by Berger’s relaxed formulations. This was the book The Social Construction of Reality, published in 1966 (English) and 1969 (German). Its subtitle refers to the “sociology of knowledge,” but not in the special sense of a sociological analysis of science, scientific research or scientific thinking; it means “knowledge” as the central feature of human existence. Therefore, the analysis of knowledge is understood as the foundation of general sociology. The second step was the Schütz-Luckmann book Strukturen der Lebenswelt, drafted by Luckmann after Schütz’s death in 1959 using a wealth of materials, texts and notes that Schütz left behind when he died. Without these books (and their impact), one might assume that Schütz would have become one of the respectable figures in the history of ideas, a case for specialists, but not the inspirational source that he is seen as today.

Propositions about interwar Vienna

This paper will focus on the original impetuses that have led to the development of the interpretive paradigm. I want to mention some of the clusters of theoretical thinking that have shaped Viennese intellectual life in interwar Vienna. I will try to emphasize the common questions, as well as diverse answers, produced by the participants in very short sketches, so that it is necessarily more “name dropping” than comprehensive content analysis.

Approaching modernity

The turn of the 19th century to the 20th saw the shift from “First” to “Second Modernity.”3 It was a decisive change in many areas of life: demographic change, the rise of scientific and technical achievements for economic progress and personal improvement, industrialization and secularization, urbanization and democratization, and new political movements, among others (Osterhammel 2011). These developments generated a new attitude toward life, even a new relationship to the world. “Human beings” were defined in a new way, not without conflicts; Darwinism had shattered human singularity; secularization demolished the “cosmion” of values; gender issues began to be debated; class conflicts were situated between revolution and reform. Everything was in turmoil. New music, new painting, new architecture – artists drafted their programs for “true art.”

These changes brought about intense feelings of insecurity: decreasing commitments and values, problems about individuality and community, and desires for belonging as well as for autonomy. The universalism of modern life collided with the urge to stay connected with one’s roots. Cosmopolitanism came into conflict with more intense feelings of nationalism; the idea of equality was restricted to national equals. But above all, insecurity was often offset by joining radical movements such as Socialist- Marxist parties or racist (anti-Semitic) movements. At the beginning of the 20th century, Europe was still the paragon of the world. Modernization meant Europeanization, and everybody aspired to European wealth. But, at the same time, the dark side of modernity was debated, and World War I created a break in self-confidence. After the war, four emperors were gone and empires demolished, the political liberalism of the old order was weakened, and new radical movements promised to reestablish old certainties and strong leadership. It was a condition of “anomie” (in a Durkheimian sense), increasingly the anomic description would meet not only the thinking and the sentiments of the people but also the working of political and economic processes.

In spite of their achievements, scholars were irritated about the basis of their knowledge. Old convictions were erased; new perceptions reframed the world; ideological aims were mixed with factual statements. How could reliable ground be found? There were philosophers who tried to find reliable truth in eternal, spiritual spheres, but this theory seemed to belong to the “old” world. In 1911, Edmund Husserl (1859–1938) wrote about founding philosophy as a “strict science” (Philosophie als strenge Wissenschaft) (Husserl 1911). In doing so, he placed himself in the tradition of Descartes, Kant and German idealism; he criticized naturalism as well as historicism. According to his arguments, philosophy must not be reduced to psychological impressions, nor must it be dissolved into incomparable (historical) cases or into simple moral/ideological Weltanschauungen. The basis must be empirical, the immediate perception with the senses: “going to the things.” The desire to struggle against impenetrability and irrationality connects Husserl with the Viennese logical empiricists, but empiricism could be understood in different versions. Radical positivists, whose methodological message is a good fit with the characteristics of the natural sciences, seemed to fail the peculiarities of the humanities (Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaften), and there were numerous theorists who tried to find a plausible middle way between these extremes.

The assumption that certain features of (meta-)theories, as they have been developed in the final phase of the Empire and in the time between the wars in Austria, were influenced by the immediate experience of the multiethnic, multilingual and multireligious environment may be justified. This may be the case with the philosophy of language (from Fritz Mauthner to Ludwig Wittgenstein), with psychology and psychoanalysis (from Sigmund Freud to Alfred Adler) or with the sociology of knowledge (from Wilhelm Jerusalem to Karl Mannheim) (Acham 2014). Edmund Husserl was a philosopher who, being confronted with a turbulent, nonconsensual world, wanted to go “back to the things,” in immediate perception, in a process of stripping all prejudgments and all foreknowledge. Alfred Schütz tried to apply his philosophical-anthropological (phenomenological) ideas to social science approaches, thereby creating a kind of (at least) proto-sociological theory. At the same time, Schütz offered a counter-model to other Viennese proposals of how reliable knowledge could be acquired. One of the best-known articles published by Schütz deals with “multiple realities.” Multiple realities were – in several dimensions – the everyday experience of people living in Vienna at that time. Peter L. Berger points to the connection of epistemological views and everyday experiences when he writes an article about “multiple realities” and therein deals with the relation of Alfred Schütz and Robert Musil (Berger 1970).

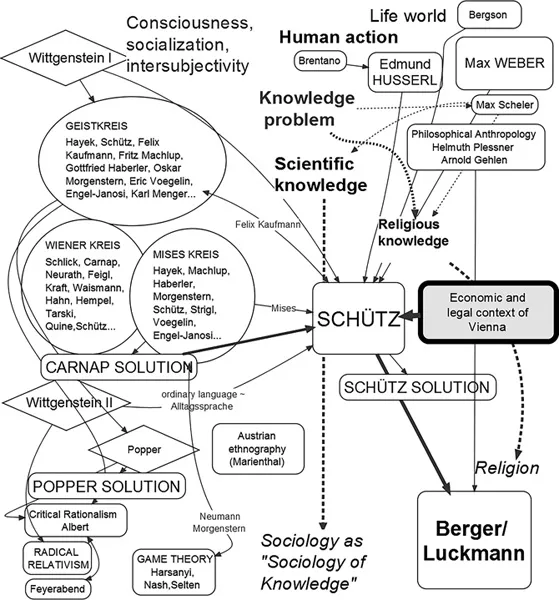

The Viennese Circles

The background of the philosophical and sociological problems that Schütz tried to solve is the discussion at the end of the 19th century and at the turn of the 20th: nomothetic and idiographic knowledge, theory and history (historicism), Verstehen und Erklären, empirism and idealism, Historical School (Schmoller) versus Marginal Utility School (Menger) and then the efforts by Werner Sombart (1863–1941) and Max Weber (1864–1920) to create a synthesis of history and theory.4 The central question was as follows: How can one produce reliable (scientific) knowledge? In the world of ideas, in a “pure sphere” separated from the impurities of real life? Or in the world of positivistic empirical observation and measurement – “logical empiricism,” in the sense of the Viennese Circle? The more sophisticated answers can be summarized as “in between.” But how might one configure that “intermediate” approach?5 The map in Figure 1.1 gives an impression of the Viennese context.

The lively philosophical discussion in Vienna started with physicists Ernst Mach (1838–1916) and Ludwig Boltzmann (1844–1906). (Mach, as a renowned physicist, was appointed to the philosophical chair in Vienna).6 First of all, mathematicians and philosophers dominated the methodological discussion.7 Economists and jurists also participated in the discourse, while social scientists were the “rare species” in the endeavor. Subsequently, with people like Moritz Schlick (1882–1936), Rudolf Carnap (1891–1970), Otto Neurath (1882–1945), Friedrich Waismann (1896–1959), Herbert Feigl (1902–1988) and other scholars, Vienna became a bulwark of empirical positivism and a stronghold in the fight against metaphysics and other “quasi-scientific nonsense” (and the dominant view of most participants in the discussion was that there was a lot of nonsense on the way in the scientific world). They were convinced that the “deepest” philosophical problems were not problems at all. After 1929, the circle started a “public phase” documented by the manifesto Wissenschaftliche Weltauffassung (Scientific World View) (documented in Damböck 2013). At the same time, after the generation of Friedrich von Wieser (1851–1926) and Böhm-Bawerk (1851–1914), the next generation of Austrian economists started scientific work, with the dominant figure being Ludwig von Mises (1881–1973) (who taught Alfred Schütz, as well as being a paternal friend and an intensive partner in discussions).

Figure 1.1 Aspects of the philosophical context of Vienna.

There were several Viennese Circles, and they did not represent a closed school or common program. Rather, it was a couple of overlapping communities fostering ongoing discussions, with divergent solutions to their problems.8 While they had no common program, they did have common problems, the most central being the universal question: How is knowledge (general knowledge, everyday knowledge) possible? And how can reliable (true) knowledge be produced? There were some sub-questions: (1) How is the acquisition of fundamental knowledge about the world possible? How can we perceive something? How can we understand other individuals (intersubjectivity)? How can we – Ego and Alter – develop a “common understanding”? (2) What is the relation of everyday knowledge and scientific knowledge? Can secure knowledge be acquired, and what is truth? How can science be “cleaned” from the supremacy of pseudo-problems? In Schütz’s terminology, since the subjective meaning an action has for a person is unique and individual, how can it be grasped scientifically, and how can it be embedded into a body of objective knowledge? (3) What is the relationship to other spheres of knowledge? Are art, religion, dreams, and ideologies a special kind of “knowledge” or something else? For the Viennese hardliners, these spheres had no place in the sciences (or in reasonable thinking at all). These are, then and now, also central questions for social constructivism, and at that time, a couple of answers were developed.

The shadow of Wittgenstein

There is a certain trajectory in the discussion about knowledge. In the 1920s, the most widespread Viennese idea was that one had to develop a procedure for designating pure, scientific knowledge. One especially had to construct a “scientific language,” a language in which no other sentences can be formulated than sensible sentences. The idea was significantly triggered by Ludwig Wittgenstein’s (1889–1951) Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, which was influenced by Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) and Gottlob Frege (1848–1925) and published in 1921, known as Wittgenstein I (Wittgenstein 2001 [1921]).9 The participants of the circle read and discussed it line by line.

In the early 1930s, when Alfred Schütz was finishing his book, the idea shifted to the opposite direction and can be summarized as follows: We will never have certain knowledge, we need to deal with the “lifeworld,” with “ordinary language,” and our knowledge will ever stay fragile. The turn was accompanied by Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, which was not published before 1953 (Wittgenstein II), but Wittgenstein’s analyses of common language, of everyday lifeworld, of language games and so on paved the way (Wittgenstein 1971 [1953]).10

Ordinary language philosophy continued with the complete dissolution of the idea of a unity of knowledge – there are different language games, and they can only be evaluated within their own scope of application or range of validity. “Real,” meaning “radical,” social constructivists sympathize with this view, which has paved the way toward postmodern and radical relativism. Radical constructivism, the wild and bolshie brother of “modest social constructivism” represented by Berger and Luckmann also started with some Austrian scholars in interwar Vienna. Ernst von Glasersfeld (1917–2010), a sort of Lebenskünstler, was impressed by studying Wittgenstein’s Tractatus, but in the opposite way: It was a completely deterring message for him. Heinz von Foerster (born in Vienna, 1911–2002), biophysicist and later founder of cybernetics, had a so-called uncle (Nennonkel) in the family: Ludwig W...