- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tycho Brahe and the Measure of the Heavens

About this book

The Danish aristocrat and astronomer Tycho Brahe personified the inventive vitality of Renaissance life in the sixteenth century. Brahe lost his nose in a student duel, wrote Latin poetry and built one of the most astonishing villas of the period, as well as the observatory Uraniborg, while virtually inventing team research and establishing the fundamental rules of empirical science.

This illustrated biography presents a new and dynamic view of Tycho's life, reassessing his gradual separation of astrology from astronomy, and his key relationships with Johannes Kepler, his sister, Sophie, and his kinsmen at the court of King Frederick II.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

ONE

Birthright Challenged, 1546–70

Beate Bille and Otto Brahe had been married two years, and she had borne a daughter named Lisbeth before Tycho.2 One year after Tycho’s birth, on 21 December 1547, came a second son, Steen, born at Gladsaxehus Castle in eastern Skåne. Now, Otto and Beate had two healthy sons, and ‘it happened by a particular decree of Fate’ that Tycho was taken away ‘without the knowledge of my parents’ by ‘my beloved paternal uncle Jørgen Brahe, who . . . brought me up, and thereafter he supported me generously during his lifetime until my eighteenth year, and he always treated me as his own son . . . For his own marriage was childless.’3 Jørgen Brahe of Tosterup was married to ‘the noble and wise Mistress Inger Oxe, a sister of the great Peter Oxe, who later became [Steward of the Realm] of the Danish royal court [and who] as long as she lived regarded me with exceptional love, as if I were her own son’.4 Tycho was five when Jørgen Brahe became governor (lensmand) of Vordingborg Castle, one of the largest commands in Denmark. Three years later, the Dowager Queen Sophie of Pomerania put him in charge of Nykøbing Castle while he remained the king’s governor at Vordingborg.

Tycho’s ‘particular decree of Fate’ meant that he was sent to grammar school at seven, ‘for my father, Otto Brahe, whom I recollect with deference, was not particularly anxious that his five sons, of whom I am the eldest, should learn Latin’.5 Jørgen Brahe and Inger Oxe wanted Tycho to become a cosmopolitan Renaissance courtier like his uncle Peter Oxe, and to be trained in Latin, Greek, the humanities and the law to serve as a diplomat, administrator and councillor.

A ten-year-old boy could hardly grasp the speed with which Peter Oxe fell from high favour in 1556 when he withdrew from court, resigned all his offices and then in June 1558 fled for his life.6 All of Peter Oxe’s brothers-in-law lost their major commands, but the Dowager Queen saw no reason to deprive Jørgen Brahe of Nykøbing Castle.

As these events transpired, Tycho was learning to read, write, speak and understand Latin with remarkable speed and was ready to enter university at the age of twelve. He came to Copenhagen and lived in the household of a professor who supervised his studies.7 When his brother Steen turned twelve one year later, however, he was not sent to school but placed in service at Vordingborg Castle as a page to Councillor Steen Rosensparre of Skarhult and Mette Rosenkrantz.8

Denmark was an elective monarchy governed by a narrow elite of interrelated families whose members occupied the Council of the Realm (Rigsråd). This body held the power to elect kings and to negotiate a håndfæstning or charter that bound the monarch to obey the law and guaranteed the privileges of all estates, and they required each king to sign such a charter before his coronation. The Council advised the king, held major commands and court offices, sat annually at Whitsuntide with the king as the supreme Court of King in Council (Retterting), and could depose a monarch who did not abide by his håndfæstning. Five senior Councillors held the high administrative offices of Steward of the Realm, Royal Chancellor, Marshal of the Realm, Admiral of the Realm and Chancellor of the Realm.9 Tycho’s father, both grandfathers and all four of his great-grandfathers sat in the Council of the Realm, and many of his ancestors held these high offices.

Councillors bore no title of nobility beyond the ‘honourable and wellborn’ (ærlig og velbyrdig) of all Danish nobles.10 Every member of a Danish noble family was noble and displayed the same coat of arms. The Brahe arms was ‘sable, a pale argent’ and the crest ‘a peacock feather upright between two urochs horns sable, a fess argent, each bearing four peacock feathers fesswise’. Patents of nobility were extremely rare, which meant that the nobility was essentially a closed caste that traced noble descent in all paternal and maternal lines.

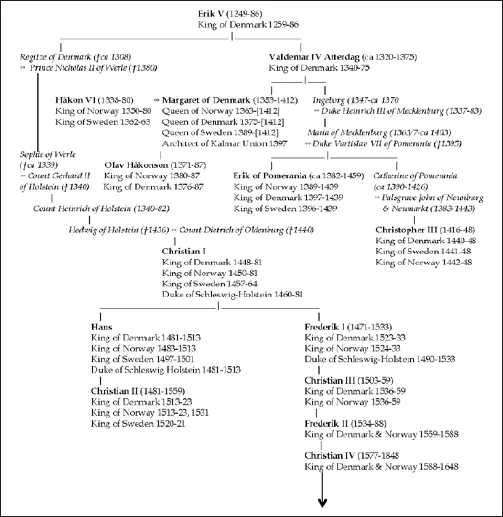

Intermarriage between the royal houses of Denmark, Norway and Sweden in the late middle ages had left a single heiress, Queen Margaret, as ruler of all three kingdoms. In 1397 her three Councils elected Erik of Pomerania as her successor but deposed him in 1439 and elected Christopher of Bavaria. When King Christopher III died without issue in 1448, the three Councils in turn elected a duke of Oldenburg as King Christian I, whose direct descendants rule Denmark and Norway to this day.11 When Christian i’s grandson, Christian II, tried to break the power of the aristocracy, all three Councils deposed him. Sweden broke away from the union, and Gustavus Vasa, Tycho’s kinsman, founded a new dynasty to rule Sweden, while Denmark and Norway elected Christian’s uncle as King Frederick I.12 Christian fled to Brabant with his Habsburg queen in 1523, and when he later tried to return in force, he was taken prisoner.

3 Peter Oxe, 1574, oil on wood.

Two years earlier in Worms, Frederick i’s eighteenyear-old son, Duke Christian, witnessed Martin Luther’s stalwart defence before Emperor Charles and became a fervent Lutheran. He implemented a Lutheran Reformation in Schleswig-Holstein by 1529 as his father’s Viceroy (Statthalter, Statholder).13 When Frederick died in 1533, aristocratic Catholic prelates persuaded the Council of the Realm to postpone the election rather than elect Duke Christian, whereupon he raised an army and conquered his father’s kingdom by force of arms.14 As King Christian III of Denmark and Norway by 1536, he deposed the bishops, proclaimed a Lutheran Reformation, and merged the Norwegian Council into the Danish Council. All Church property – around onethird of the entire Kingdom of Denmark – was confiscated and added to the royal domain. The monarch was more powerful than ever before in a vast realm that reached from the Elbe to North Cape and from Iceland to Gotland. His Council of the Realm now consisted entirely of Danish and a few Norwegian landed aristocrats, including all the families of Tycho’s kinship. Crown and Council in ‘strategic alliance’ established a highly centralized Lutheran ‘diarchy’ led by a patriarchal monarch whose court was characterized by order, piety and moderation.15 The immense royal domain was administered by councillors and their kinsmen at the pleasure of the king.

4 Kings of Denmark, 1249–1648.

5 Matthäus Merian the Elder, Following in the Footsteps of Nature, 1618, engraving.

In the wake of Christian III’S Reformation, Copenhagen University was reorganized on the model of Wittenberg with Philip Melanchthon’s studia humanitatis as the entry to all further studies. Just as Martin Luther had pushed aside centuries of commentary and returned to the original sources of Christian theology in the New Testament and Church Fathers, his friend Philip had returned the seven liberal arts to the sources of wisdom – ad fontes – of classical Latin, Greek and Hebrew. Asserting that Cicero and Seneca were more enjoyable than medieval commentaries, Melanchthon immersed students in classical literature and instilled in them the humanist virtues of eloquence, erudition and prudence as well as Lutheran theology and morals.16 Tycho thrived on these studies and soon discovered Ovid to be his favourite poet.

In his second year at university, a partial eclipse of the Sun occurred on 21 August 1560.17 Astronomy was not part of preparation for the law, so Tycho was not allowed to attend lectures in the subject. He responded by buying books and studying astronomy on his own.18 His edition of Johannes de Sacrobosco’s De sphaera (On the Spheres) contained a preface by Melanchthon that linked astronomy with astrology, which in turn connected the stars to the human microcosm. Melanchthon asserted that astronomy was ultimately a search for the divine mathematical laws that both governed celestial motion and were the ‘manifest footprints of God in nature’.19 Luther taught that Divine Law was written into the laws of Nature as well as Holy Scripture. His theology distinguished between Law and Gospel and asserted that the two forms of Law led us towards faith in the Gospel, the ‘good news’ that Christ died for our salvation.20 Tycho’s understanding of astronomy-astrology was shaped by these ‘Philippist’ and Lutheran ideas.

Sacrobosco explained the ‘doctrine of the spheres’ as the first part of astronomy. The annual path of the Sun circled a plane called the ‘ecliptic’ that ran through the centre of the ‘zodiac’, divided at 30° intervals into ‘houses’, and it crossed the celestial equator (equinoctial) twice a year at the ‘equinoxes’. The ‘zenith’ was directly above an observer, and the ‘horizon’ surrounded him. Every celestial body reached daily ‘culminations’ at its highest and lowest points on the observer’s ‘meridian’, a great circle through the poles.21 Sacrobosco also explained Earth’s seven climate zones, how eclipses were caused, and how the Sun, Moon and five planets were carried around the zodiac on combinations of circles.

The second part of astronomy was the ‘theory of the planets’, which had been in dispute ever since Nicolaus Copernicus’ Sun-centred cosmology appeared three years before Tycho was born. Sacrobosco followed an alternative system based on the physics of Aristo...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface: Denmark and the Renaissance

- 1 Birthright Challenged, 1546–70

- 2 Cloister into Observatory: The New Star, 1570–73

- 3 Finding a New Life, 1573–6

- 4 Treasures of the Sea King: Kronborg and Uraniborg, 1576–82

- 5 Star Castle: Going Down to See Up, 1582–8

- 6 On the Move, 1588–99

- 7 The Emperor’s Astrologer and his Legacy, 1599–1687

- References

- Further Reading

- Acknowledgements

- Photo Acknowledgements

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Tycho Brahe and the Measure of the Heavens by John Robert Christianson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & European Renaissance History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.