eBook - ePub

Impressionism: A Feminist Reading

The Gendering Of Art, Science, And Nature In The Nineteenth Century

- 194 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Impressionism: A Feminist Reading

The Gendering Of Art, Science, And Nature In The Nineteenth Century

About this book

An original interpretation of Impressionism and nineteenth-century art and culture by a noted feminist art historian. This book is a pioneering reading of Impressionism from a feminist perspective by a noted art historian. Norma Broude analyzes the philosophical underpinnings of landscape painting in the late nineteenth century discussing the crit

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

Impressionism and Romanticism

The Impressionists did not come of

nothing, they are the products of a steady

evolution of the modern French school.1

nothing, they are the products of a steady

evolution of the modern French school.1

—Théodore Duret, 1878

While most general accounts of the Impressionists briefly acknowledge the artists' Romantic predecessors and their involvement with nature, the precise ways in which the tradition of Romantic landscape painting might have continued to be meaningful to the Impressionists have never been adequately explored. Instead, the Romantic landscape painters have themselves often been treated ahistorically in this context, as impressionnistes manqués. In evaluating the importance of the Barbizon painters for the Impressionists in her book of 1967, for example, Phoebe Pool wrote: "Eventually, artists [i.e., the Impressionists] were to become more interested in the small dabs of paint than in what they represented. But Millet, Rousseau and Daubigny did not reach that point; they still had a more Romantic interest in nature."2

A similarly distorted, evolutionary view was also applied in the twentieth century to discussions of John Constable and J. M. W. Turner, who, for a long time, were essentially understood and valued as precursors of Impressionism.3 This ahistorical approach to the Romantic landscape painters has been corrected by recent scholarship, which encourages us to look at Constable and Turner in the context of their own Romantic predecessors and contemporaries—artists such as John Crome, Alexander and John Robert Cozens, Philip de Loutherbourg, Caspar David Friedrich, and Théodore Rousseau—rather than as incomplete steps on the path toward the twentieth century's mistaken notion of a naturalist and formalist Impressionist ideal.

It is time now to extend to the Impressionists as well the implications of the late twentieth century's revised and historically more viable attitude toward Constable and Turner—to shift our perspective, in other words, so that the Impressionists, too, may be placed more consistently and more meaningfully within the context provided for them by their own predecessors and contemporaries—artists such as Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, Charles François Daubigny, and Johan Barthold Jongkind, as well as Constable and Turner. Approached this way, the formal and expressive resemblances between a Turner and a Monet, for example (colorplates 4 and 5; 14 and 15), would no longer be seen as a surprising prefiguration of the later artist on the part of the earlier one, but as the period itself would have been inclined to see it, as a growth and development of the later artist out of a tradition exemplified by the earlier one. As the French novelist and art critic Théophile Gautier wrote in 1877 on the relationship of the contemporary present to the Romantic past: "Today has its roots in yesterday; ideas like arabic letters are linked to what has come before and to what follows."4

CHAPTER 1

Thematic Continuities

In his book Monet at Argenteuil (1982), Paul Hayes Tucker describes the rapid encroachment of industry and urban blight in the 1870s that finally impelled Claude Monet to leave the once charming suburban town of Argenteuil, where he had made his home from 1871 to 1878, and to take refuge in the more isolated and still idyllic town of Vétheuil. He describes, too, how in the pictures painted during Monet's years in Argenteuil, the artist consistently turned his back on the uglier and more unpleasant aspects of the changing environment there.5 But Tucker does not infer what we might be tempted to call Romantic escapism from these actions; in fact, he concludes that for most of the six years that he spent in Argenteuil, Monet's pattern of activity showed him to have been an artist who was committed to the principles of modernity and progress, an artist whose work was "celebrating progress, the new religion."6

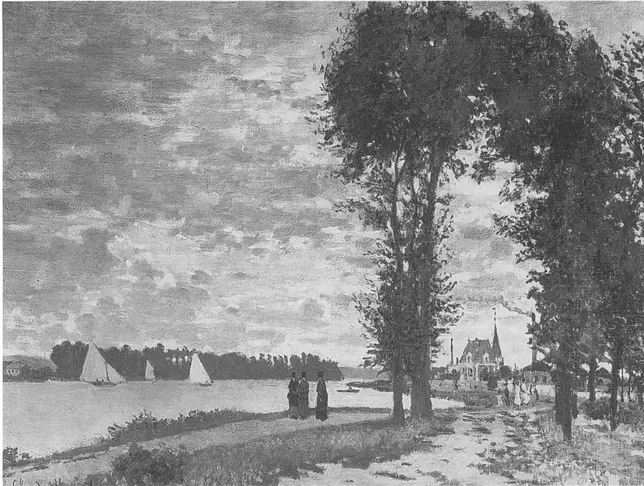

The assumption of an unbridgeable gulf between Impressionism and Romanticism is thus as pervasive in the recent sociohistoric literature on Impressionism as it was in the older formalist canon. It was also perpetuated, ironically, in the work of Robert Rosenblum, whose 1975 book Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition: Friedrich to Rothko presented a new and daring alternative reading for the history of modern art, a reading based upon a vision of the centralily of the northern Romantic tradition. Rosenblum persuasively charted a vital and continuous current of Romantic feeling in the art of northern Europe and the United States from Friedrich to Rothko—virtually down to the present day. He saw this continuity, however, only in art that is overtly transcendental or symbolic in its structure or in its imagery and content. And in order to define the character of this art, he depended heavily on the conventional view of Impressionism—and in particular the art of Monet—to provide a contrasting foil. Of a typical Impressionist landscape, Monet's The Banks of the Seine at Argenteuil of 1872 (fig. 1), he therefore wrote:

The picture includes almost every motif from which Friedrich extracted such portentous symbols—figures standing quietly on the edge of a body of water; boats that move across the horizon; a distant vista of a building's Gothic silhouette, enframed by almost a nave of trees; and even a rather abrupt jump from the extremities of near and far. Yet, somehow, though the painting conveys a gentle, contemplative mood, it also insists on the casual record of particular facts at a particular time and place. The clouds will shift, the figures will move, the trees will rustle in the breeze, the boats will pass. That quality of the momentary, of the random, of the specifically observed, thoroughly counters Friedrich's solemn and emblematic interpretation of the same motifs.7

As Rosenblum observed, "almost every motif" that is familiar to us in Friedrich's art recurs here. This is what should give us pause when we consider the differences between these two artists. It should encourage us to reexamine our emphases and to ask if we may not have been overstating those differences in conformity with the rule of polarity that was for so long fundamental to art historical thinking about this period.

1. Claude Monet (1840—1926).

THE BANKS OF THE SEINE AT ARGENTEUIL. 1872.

19 ¾ × 25 ½″ (50 × 65 cm). Ronald Lyon Collection.

Photograph, A. C. Cooper, Ltd.; courtesy Christie, Manson & Woods Ltd., London

THE BANKS OF THE SEINE AT ARGENTEUIL. 1872.

19 ¾ × 25 ½″ (50 × 65 cm). Ronald Lyon Collection.

Photograph, A. C. Cooper, Ltd.; courtesy Christie, Manson & Woods Ltd., London

Certainly, the differences in mood and inflection between Impressionism and German Romanticism, which Rosenblum and others would emphasize, are obviously there. Even in the rare Friedrich landscape where the sun shines and the figures engage in relatively unambiguous, leisure-time activity, as in Chalk Cliffs on Rügen of 1818-1820 (colorplate 8), the human figures are still portentously dwarfed by the colossal forms of nature. In this instance, three well-dressed people, identified as the painter himself, peering over the edge of the cliff, with his wife, Caroline, and his brother, Christian,8 are shown exploring the rugged and brightly illuminated landscape on an island in the Baltic. Like them, we cling to the rocks in the foreground, in awe of the abyss below, separated physically by insurmountable spatial barriers from the vastness of the sea and the almost supernatural glow of the light-filled space beyond. Despite the specificity of the place, the people, and their activity, the symbolic implications of the image are unmistakable. The sea here, as in Friedrich's other pictures, can be interpreted as a symbol of infinity, and the ships that move upon it as a symbol of human destiny and transience. In the face of this, a comparable work by Monet provides a marked and misleadingly easy contrast in mood. In the Garden at Sainte-Adresse of 1867 (colorplate 9), Monet's vacationers, also well-dressed members of his own family, sit on a broad and comfortable terrace, which is fenced and smoothly landscaped. Here, there are no luminous and awe-inspiring depths, no rugged and threatening terrain. Instead, flags flutter in the breeze, sailboats and steamships move toward the horizon, and all ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- PREFACE

- INTRODUCTION. On Impressionism and the Binary Patterns of Art History

- PART I Impressionism and Romanticism

- PART II Impressionism and Science

- PART III The Gendering of Impressionism

- NOTES

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Impressionism: A Feminist Reading by Norma Broude in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.