Regional Introduction

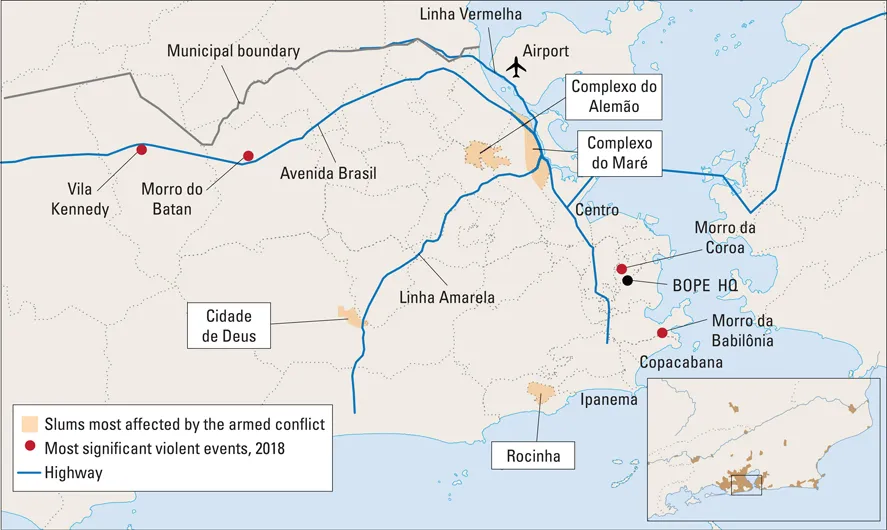

The five armed conflicts currently active on the American continent share various characteristics and one key driver. In Colombia, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico and Rio de Janeiro, organised criminal groups fight one another and the state to control the production, distribution routes and sale of illicit drugs, both within the countries where they operate and across their borders. Commonly referred to as drug-trafficking organisations (DTOs), criminal syndicates or cartels, the non-state armed actors in these conflicts are in fact neither monolithic nor hierarchical organisations. Instead, they compete and use armed violence to control territory rather than coordinating to fix market prices (as economic oligopolies do). They engage in various illicit activities, diversifying their portfolios beyond the drugs trade (including arms trafficking, people smuggling, kidnapping for ransom and protection rackets), or enter the narcotics business having evolved from their insurgent origins (as in the case of the National Liberation Army (ELN) in Colombia). Urban militias establish sophisticated extortion systems to exploit local resources and businesses (as in the case of Red Command (CV) in Rio de Janeiro’s slums).

Although the criminal bands (BACRIMs) in Colombia, the maras in Central America and the cartels in Mexico depend on international networks for their main sources of business and income, their activity is deeply rooted in local dynamics. The drivers and consequences of these armed conflicts are closely intertwined with local communities and institutions and shaped by specific national policies and politics. Crucially, while seeking to maxim-ise profit, Latin America’s criminal organisations establish sophisticated systems of social control and capture state structures. Armed groups recruit foot soldiers locally and exploit poverty, marginalisation and limited state reach. They also penetrate enforcement institutions at every level, through bribery, collusion, intimidation and violence.

The conflicts in Latin America also expose the limits of the analytical distinction between political and criminal wars. Rather than fighting the state to challenge, change, substitute it or secede from it, the armed groups in Colombia, Central America, Mexico and Rio – with the (mostly nominal) exception of the ELN – are criminal organisations without a political agenda. Instead, they seek profit, of which the international narcotics trade offers a virtually limitless source. If this key objective sets them apart from traditional, politically motivated insurgencies, it is their organisational capacity and willingness to engage the state in sustained armed confrontation that establishes them as parties to armed conflicts – if anything, ones with particularly formidable resources to fight their enemies. Similarly, just like ideologically or politically motivated groups, armed criminal groups distort social behaviour, hollow out democratic practices, erode the rule of law, disrupt local and national economies, hamper development in marginalised areas, force displacement and victimise civilians.

No official statistics exist on the casualties of these conflicts, yet there are indications that they are high. The Office of the Prosecutor General in Colombia estimates that around half of the homicides in 2018 were a result of clashes between criminal groups or were perpetrated by hitmen working for these organisations. In Mexico, media and civil-society organisations estimate cartels-mandated executions to be in the thousands. Approximately 1,000–1,500 people were killed in Rio de Janeiro this year during security operations. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) consistently ranks El Salvador’s and Honduras’s homicide rates among the highest in the world. Although intentional homicides form the basis of these statistics and are therefore not comparable as such to the metrics of conflict-related fatalities (including those used in this publication), they offer a sense of the magnitude of the problem and the impact of violence on the people living in the crossfire of criminal organisations.

Decades-long efforts to defeat these groups have failed and at times even escalated violence (as in the case of Mexico’s decapitation strategy to eliminate the cartel leaders, or Central America’s Mano Dura (‘Iron Fist’) policies). Law enforcement in the region faces two main challenges. Firstly, human-rights violations against the civilian populations are widespread. In Colombia’s rural districts, with the realisation that the demobilisation of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia—People’s Army (FARC–EP) would not bring the hoped-for peace dividends, dissident groups have returned to disappear civilians and tax the sale of coca paste. Secondly, throughout 2018, thousands of people from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras embarked on the perilous journey to the US border to escape rape and sex slavery, constant death threats, extortion and forced recruitment by the gangs. They reported, however, to be often more scared of the police back home. Lacking the capacity and viable intelligence to confront the gangs effectively, Honduran and Salvadoran security forces harass the small fish, targeting youth who fit the profile of gang recruits.

Criminal organisations seek to maximise profit and establish systems of social control

At the policy level, state responses have focused on increased militarisation and ever-harsher measures. In 2018, politicians who promised a strong approach to organised crime won the presidential elections in three of the region’s countries. In Brazil, presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro pledged to wage war on violent crime in Rio’s favelas and to grant immunity for crimes committed by on-duty police. President Iván Duque campaigned against a peace agreement with the ELN – Colombia’s last remaining Marxist–Leninist guerrilla group that controls much of the country’s coca-growing regions – cancelling talks a month after his inauguration. Duque also delivered on promises to roll back certain provisions of the peace agreement with the FARC–EP, including lenient judicial measures for former armed-group members who submit to the truth and reconciliation process. The campaign tone of Mexico’s President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) was different. Since his inauguration in December, however, he has proceeded to create a National Guard – an elite military police focused on combatting drug cartels. While hybrid forces and joint operations have shaped the responses to armed groups in Brazil, Colombia and Mexico, and the armed forces have taken on an increasing number of national-security roles, police resources have been neglected. Positive results from military measures are still to materialise, but their potential to weaken the discredited law-enforcement institutions is easy to foresee.

Although not fully fledged armed conflicts, Guatemala and Venezuela are the situations to monitor in 2019. President Nicolás Maduro’s government has responded violently to peaceful demonstrations demanding an end to its rule, with the proportion of deaths due to police and military action on the rise in 2018, according to local organisations. The humanitarian crisis continues to deteriorate, with medicine and food shortages, spiralling child mortality and malnutrition, and increasing displacement to neighbouring countries. Civil militias have supported the recent military repression of anti-government protests, beating demonstrators while passing through the crowds on motorbikes. The opposition’s loose organisation and peaceful stance, and the armed forces’ cohesiveness, have so far prevented the situation from escalating into an armed conflict, but it is unclear how long they will continue to do so. Meanwhile, Guatemala faces many of the same challenges as El Salvador and Honduras: gang-dominated trafficking, weak security forces and dysfunctional judicial institutions. Although the maras operating there have not reached the organisational sophistication of those in the neighbouring countries, they may soon pose a similar threat to the Guatemalan state.