The labour landscape in India has seen several changes subsequent to the introduction of labour market deregulation policies. The sectoral and structural changes, as studies have already highlighted, include increase of atypical employment as part of the general expansion of informal sector (Nath 1994; Gupta 1995; Despande and Despande 1998; Maiti and Mitra 2010), informalisation of formal sector (NCEUS 2009; Goldar 2010), decline in real wages and well-being (NCEUS 2007; Papola 2008; Institute for Human Development 2014; George 2016), decline of agriculture and allied sectors (Bhalla and Singh 2009; Rajkumar and Shetty 2015), stagnation of manufacturing sector (Agarwal and Ghosh 2015; Roy 2016) and expansion of certain segments of service sectors (Rajkumar and Shetty 2015). The past two decades also witnessed a decline of trade union membership in India, which is generally attributed to developments such as transformations in production systems, labour market and employment relations.

Among others, what probably rearrange or determine the labour space are the production processes, labour relations and labour control and disciplining strategies by the employer and through laws enforced by the state and the way in which workers respond to these. These processes can also create particular patterns of labour spaces and certain “dominant discourses through various channels in the public sphere” (Castells 1998). For instance, the added focus on economic growth and its preconditions of labour market flexibility always come with the proposition that trade unions are obstacles to growth. While such moral economic explanations of growth are pervasive and dominant in any liberalised economy like India, what is perhaps less discussed is the way in which labour is losing its space in the production landscape and the capability of such policy discourses to create an antipathy to any form of organisation of workers in the public sphere, as is evidenced in the public and mainstream media reactions to the recent strikes in various manufacturing and service sectors. In this context this chapter attempts to critically understand the contemporary labourscape and labour space in India. The labourscape here refers to the structure, composition and nature of work and workforce in various sectors. Labour space implies the space available/created for labour to engage with capital and state including its agencies of governance at various levels in addressing their collective concerns and everyday struggles through various means at both macro and micro levels. The specific questions that the chapter aims to deal with are as follows: What is the nature of Indian labourscape in terms of forms, types and characteristics of employment, wages, collective organisation and labour resistance. What are the contemporary dominant discourses that create and appropriate the labour space? Finally who are the actors in it and how do they do it?

The contemporary labourscape

Several studies have already highlighted that labour market reform policies, which emphasised on flexibilisation of labour laws, retrenchment and closure of large-scale industrial activities as part of flexible specialisation, disinvestments, privatisation and subsequent casualisation of work, had an adverse impact on labour in India (Breman 1996, 2001; Bhowmik and More 2001; Mahadevia 2001; Ghosh 2008). The significant factors that condition the contemporary Indian labour landscape perhaps are the intra-and inter-sectoral changes in agriculture, manufacturing and services; casualisation of jobs and informality in labour relations.

Among others, the paradox of decline in the share of agriculture and manufacturing in GDP, despite its continuing higher share of employment along with the expansion of service sector without correspondingly generating employment, which set the Indian labourscape, needs some attention here. The data as extracted from the national sample survey 68th round on employment and unemployment, for instance, showed that agriculture, forestry and fishery still account for more than 50 per cent of employment in rural India (see Table 1.1). Similarly, manufacturing and construction together account for nearly 24 per cent of the Indian workforce. The share of manufacturing in urban India is 21 per cent. The service sector expansion is highly urban centric and limited only to certain segments of industrial categories such as wholesale and retail, transportation and storage, information and communication, real estate, public administration, education, health and social work, which constitute nearly 56 per cent of urban employment. Out of these the highest share is from the traditional wholesale and retail sector and repairing works. This uneven growth and employment in these sectors considerably determines and affects the labour relations

Table 1.1 Workforce distribution across industry, 2011–12

and conditions of work. Most importantly, it sustains and expands the prevailing informality in employment since better jobs are limited only to certain segments of public sector and service sector, where the growth is without producing new jobs.

The official data endorses this trend of growing informality along with the expansion of informal sector in India. Informal employment in India has shown a trend of expansion since the 1990s with the privatisation of public institutions, casualisation in the formal sector and as part of the overall growth in the informal sector. The National Committee for Enterprises in Unorganised Sector (2007) report estimated that informal employment in India was as much as 394 million (about 92%) in 2004–05 with an increase of 54 million from 1999 to 2000. The report also highlighted that informal jobs in the formal sector showed an increasing trend in India with 29.1 million in 2004–05 as compared to 20.5 in 1999–2000. Estimations based on NSSO data on employment and unemployment (2009–10) revealed that 94 per cent of India’s workforce is in the informal sector. The NSSO 68th round data shows that informal employment in 2011–12 in India stood at 93.2 per cent (Table 1.2). Also, informal employment is more in rural India as compared to urban India. While it is nearly 85 per cent in urban India, 97 per cent of employment in rural India is informal in nature.

Informal employment also showed significant gender dimensions. The overall share of female employment in non-formal sectors at all-India level is nearly 97 per cent, while it is a little less than 90 per cent for men. Rural India has the lowest share of women working in formal regular salaried sector with a share of 1.34 per cent as against 5.43 per cent men workers. The male–female differential is notably higher in urban India, where the share of men in non-formal work is 76 per cent and the corresponding share of women is as much as 94 per cent. Other noticeable inference, which is adding to the skewed gender distribution, is the considerable lower presence of women in the section of self-employed own-account worker and self-employed employer, which are relatively better categories of work in terms of remuneration and conditions of work, both in rural and urban India. For instance, their under-representation is significant in self-employed own-account worker (2.8% for women against 20.5% for men). There are certain sectors where female employment is over-represented also. They are considerably over-represented (as compared to men) in the non-/less economically recognised sectors like domestic duties (rural 18.48% and urban 36.38%) and collection of goods/sewing/tailoring/weaving for household (20.3%). Data from Census 2011 also show the lower rate of work participation of women in the group of main workers as compared to men and the higher rate in the group of marginal workers.

Table 1.2 Percentage of population by usual principal status by gender and sector, 2011–12

Main workers are those who worked for more than six months a year, and marginal workers include those who have worked for less than six months. While men constituted 45.1 per cent in the group of main workers as per the Census 2011 figures, the corresponding share of women was as low as 14.7 per cent. However, women outnumbered men in marginal work, reiterating the linkages of women’s work in the less protected sectors. While women constituted 11 per cent in the group of marginal workers, it was 6.6 per cent for men.

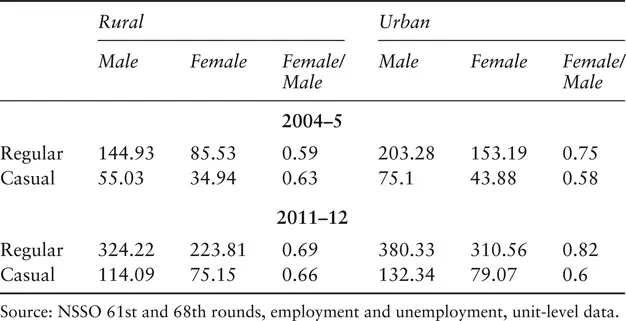

While data show a steady increase in the informal employment, it is important to understand whether such employments are “decent” and remunerative. We have taken indicators such as wages, availability of social security benefits, nature of job contracts, eligibility for paid leave and mode of payment of wages to understand the informality of employment. Have wages in the informal sector grown? Data show that wages of casual workers both in the rural and urban India increased between 2004–05 and 2009–10 (Table 1.3). It recorded an increase by Rs 59 for males and Rs 40 for females in rural India and Rs 57 for males and 36 for females in urban India. Data show that the real wages (inflation-adjusted wages) of casual and regular workers also improved in this period. What is important, however, here is the persisting male–female wage differentials for casual and regular workers and a huge gap in wages between the casual and regular workers.

Similarly, reinforcing the argument of informality and appalling conditions of work, the data showed that as much as 80 per cent of rural and 63 per cent of urban workers do not have any social security entitlement (see Table 1.4). They belong to the most exploited section

Table 1.3 Average daily wages of regular and casual workers, 2004–5 and 2011–12

Table 1.4 Social security measure available across industry groups

of the Indian workforce. Only 8.3 per cent of the working population in rural areas and 18.21 per cent in urban areas have all social security benefits including provident fund, gratuity, healthcare and maternity (only for women). Construction sector has the highest share (92.61%) of workers without any social security benefit. Agriculture, forestry and fishery sectors (primary sector), where 44 per cent of Indian work-force is employed, have workers as much as 85.27 per cent without any form of social protection. Other sectors where workforce share is high and social security entitlements are low are manufacturing, wholesale and retail. While Indian manufacturing sector employs 12 per cent of the workforce, 74.74 per cent of them are without any social security entitlement. Similarly, 84.67 per cent of workers in wholesale, retail and associated sectors, which employ 11 per cent of the total work-force, do not have any form of social security.

Data on availability of social security provisions also enable us to understand the extent of casualisation in other sectors as well. What is important to note is that one can find considerable share of casual workers, who are without any means of social protection even in the modern service-led sectors. For instance, only 25 per cent of the workers in the information technology sector have all social security provisions (PF/pension and gratuity and healthcare and maternity benefit) and 30 per cent in this sector work without any social security measure. Similarly, nearly 26 per cent in the financial and insurance activities, 32 per cent in real estate, public administration and technical work and 33 per cent in education, health and social work sectors are not covered under any social security scheme.

Another important indicator, which explains informality, is the type of job contract. Data show that nearly 85 per cent of workers in rural and 72 per cent in urban India do not have a formal written contract with the employers (Table 1.5). It is not surprising from rural India since more than 50 per cent of employment is in the primary sector, where work is mostly on a daily basis as well as seasonal. Non-agriculture sector in rural India is also highly informal in nature, and only 12 per cent workers in rural India were with more than three years of work contract. Similarly, only 22 per cent of workers in urban India had a written job contract of more than three years. Among various industrial sectors, the informality in terms of absence of job contract was the highest in construction. While the sector accounts for 12 per cent of the Indian workforce, as much as 97 per cent of them were without a written job contract. Similarly as much as 89 per cent of workers work without any formal job contract in wholesale and retail sector, which employs 11 per cent of the workforce. The story