- 154 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book brings a practitioner's insight to bear on socially situated art practice through a first-hand glimpse into the development, organisation and delivery of art projects with social agendas. Issues examined include the artist's role in building creative frameworks, the relationship of collaboration to participation, management of collective input, and wider repercussions of the ways that projects are instigated, negotiated and funded. The book contributes to ongoing debates on ethics/aesthetics for art initiatives where process, product and social relations are integral to the mix, and addresses issues of practical functionality in relation to social outcome.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part 1

Contexts and Case Studies

Part 1 outlines a series of collaborative and participatory art projects with communities realised over a period of forty years. To help differentiate the changing social and political conditions of the times and the way that these factors have informed the nature of the practice, the projects are grouped into decades, which in some cases also reflect the span of the organisations through which they were realised. Since no project arose from a vacuum, I have indicated the processes and procedures through which each has evolved, the relationships underpinning them, lessons learned from the experience and how each has laid the foundations for subsequent practice. I conclude with some comments in hindsight on structures, principles and methods that have run through the work as well as the precarious nature of the whole endeavour.

1 Seventies

In 1973, Lucy Lippard published Six Years: Dematerialisation of the Art Object, tracing the move from minimalism through conceptualism to “process art” from the late sixties to early seventies1. It marked a moment when post-modernist thought in the visual arts was becoming reflected through increasing interest in process over product and a proliferation of new art forms. Individual creative authorship came under question, as did the role of the artist in relation to society. Marxist theory, particularly Gramsci’s notion of hegemony, informed the growth of activist art practice of this time. Reflecting back on that decade, Beyond the Fragments by Sheila Rowbotham, Lynne Segal and Hilary Wainwright helped identify this time as an era in which previously passive or angry individuals and groups in isolation, such as women, gays, blacks and youth, became militant and organised2. In Community, Art and the State Owen Kelly surveyed this period in terms of creative work with communities and identified three distinct types. The first was the creation of new and liberating forms of expression, as in the work of the Arts Lab (precursor to the London Institute of Contemporary Arts). The second was the movement of fine artists out of the gallery and onto the streets. The third was a “new kind” of political activist who believed creativity to be an essential tool in any kind of radical struggle3.

The first of these models was characterised by individual artists, particularly in Europe, using the gallery as a public arena for political activism. Conrad Atkinson, for example, staged his Strike at Brannan’s exhibition at the ICA in London in 1972 to document ongoing industrial action at a thermometer factory in Cumbria. Workers held meetings in the gallery and one outcome of this public event was the unionisation of the factory’s London branch. There was also significant arts activism in Germany—Hans Haacke was busy exposing the financial workings of big business, while Klaus Staeck brought together art and activism in political posters. Perhaps most influential to my own practice was Joseph Beuys. Crossing traditional and organisational boundaries, he saw the artist as a key player in social transformation, establishing the Free International University as a framework for interdisciplinary interaction and, briefly, a real institution. I was fortunate to experience at first hand this combination of political, issue-based thinking with art and education through my early involvement with events connected to his initiatives. Caroline Tisdall, my Art History tutor at University of Reading, had worked closely with Beuys for many years, and through her I not only came to hear Beuys speak, but was also included in meetings and events where current issues were debated from an interdisciplinary perspective. These experiences were shared with Peter Dunn, a fellow Fine Art undergraduate with whom I began an ongoing collaboration. In 1977 we were invited to participate in a “discussion room” set up for debate on social issues established by Beuys at Documenta 6, where we were able to test our emerging practice in an international forum. These experiences, with their concepts of cultural production as a catalyst for change and new ideas generated by interdisciplinary collaboration, laid important foundations for our subsequent practices.

The work of these artists with political agendas was nevertheless gallery oriented, and another form of art that characterised this era proved similarly influential. “Cultural democracy”4 was the philosophy that underpinned the Community Arts movement. It recognised cultural plurality and took the premise that everybody is creative and has the right to express their ideas through creative means. Among its primary concerns was the decentralisation of cultural resources, production and distribution, aiming to move cultural production from a system in which ideas and products were transmitted from centralising sources to one in which they would be produced and distributed from the many local and regional sources where they occurred. Emphasis was also placed on support for the subsequent federation or net-working of these resources, although its central premise remained the empowerment of ordinary people and communities through the arts5. In comparison to the mainstream, this movement was highly organised and subject to self-examination, with much of its debate in the late seventies and early eighties taking place through the Association of Community Artists. Two key conferences were organised in the UK. Friends and Allies was held in Salisbury in 1983 and Another Standard in Sheffield in 1986, the latter paralleled by a US event ImaginAction in Boston Massachusetts the same year. The sector was successful in securing funding and gained recognition from both local government and the Arts Council of Great Britain. It was also largely responsible for influencing the way that art was funded through the Greater London Council following the election of a left Labour majority in 1981. In this seat of metropolitan government Community Arts gained its own sub-committee status with an increasing £1m annual budget, resulting in half a decade of prolific arts activity in the capital.

Feminism was a similarly growing force at this time. Conscious-raising groups were becoming more widespread, awareness of women’s achievements was growing, and women felt increasingly supported in standing up for their rights as equal citizens both within and outside of the patriarchal establishment. From the perspective of the third millennium it is hard to fathom the extent of the limitations that continued to be placed on women in the home and workplace in that very recent historical period. These issues were both reflected in, and on occasion, led by the arts and one of the many creative initiatives that for me made enormous impact was the exhibition Women and Work: A Document on the Division of Labour in Industry by artists Margaret Harrison, Kay Hunt and Mary Kelly at South London Gallery following the introduction of the Equal Pay Act in 1975. Feminism remains an important driver for my work, both reinforcing and supporting key concerns and approaches. Although women’s issues are not often represented directly in my practice, it has nevertheless always centred on some of feminism’s key tenets, such as social and civil rights, redistribution and recognition, making visible, giving voice, a refusal to dwell on appearance, a striving for equality, identities explored from the inside out, and the creation of narratives that counter the dominant.

In the projects outlined below I trace the development of these ideas, many of which originated in that time. The process has been aided by an overview afforded by Art for Change, a retrospective exhibition and catalogue6 of my collaborative work that was initiated, researched and staged by the Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst in Berlin in 2005. The organising team, led by the cultural academics and activists Carmen Mörsch and Katja Jedermann, was keen to contextualise the work in a way that is still rare in exhibitions of contemporary arts, and the experience prompted me to consider the practice as a totality, providing the groundwork for the survey of accumulated experience that follows here.

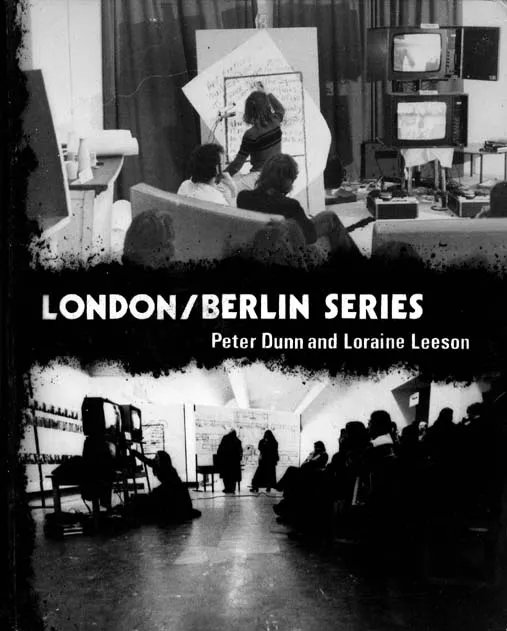

London/Berlin Series, 1975–76

With so many of my undergraduate influences coming from Germany, it followed that, on completion of my undergraduate studies, I applied to the British Council for a DAAD7 scholarship, which took me to Berlin in the autumn of 1975.

I was not however prepared for the traditionalism of the institution in which I found myself. At that time the Hochschule der Künste trained student artists for six years under the same professor, mainly in highly conventional media with none of the debate or critique of which I had come in search, and that certainly manifested itself in subsequent years8. This was in contrast to the cultural activism of the seventies art school scene in the UK, and particularly my experience of the Slade School of Art in London, where Peter was undertaking graduate studies and I was an associate student. In response to these contrasting experiences, Peter and I began to work together on a series of simultaneous performances between the two universities. These events questioned the context of art, the role of the artist, the relation of the individual to the group and the nature of collective cultural action. Initially enacted through a series of telephone conversations and personally transported written instructions, the processes employed were precursor to the digital projects involving communications technologies of later years. There is no doubt that the assertions embodied in that work relating to the constraints of art institutions and the desire to work in a wider social sphere have continued to underpin my practice.

For the first performance Peter made a drawing of the “individual private space” of his London studio, while I worked with a group in Berlin to translate this into physical form. We used soil and charcoal on the floor of a communal workspace at the Hochschule der Künste to recreate the studio as a metaphor for a “contextual frame” and write out questions about the context of art activity originated by Peter in his studio, then debated these as a group. Our amendments to the original statements were phoned back to Peter, who in turn incorporated these new ideas into his design. Photographic and video documentation of these events were later taken to a group event at the Slade, where the issues were further developed through discussion. Finally all the material was brought back to Berlin for the German end of the debate. I had in the meantime been working on an addition to the exhibition and discussion that we planned to stage there that responded to my perceived isolation of the educational experience of students at the Hochschule der Künste. Knocking on the door of every studio in its vast neoclassical building, most of which were locked, I asked any students present to photograph the interior and write a comment on communication. These were then pasted onto a plan of the building, constituting another frame that brought to light interior spaces, and indeed whole departments, hitherto unknown to many of the students there, as well as common concerns on issues of communication.

Figure 1.1 London Berlin Series book

© Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson 1975–76. Hand-made book documenting a series of performances, video and installations between London and Berlin, questioning the context of art and role of the artist.

This early attempt by Peter and myself at collaborative working had proved fruitful, particularly since the work itself was based on dialogue and interaction. From that time we continued to work together on projects or individually through organisations that we co-founded, until the late nineties. We saw our work neither as community art, nor what was often at the time referred to as “gallery socialism”, indicating those who “dipped into non-art contexts” using visual forms that were only comprehensible from an art world perspective. “Transitional practice” was a term that we often used to describe our position at that time, and indeed at this juncture we were in transition from working inside an institution to stepping out into the wider world, as we attempted to do in the next project.

The Present Day Creates History, 1976–77

The London/Berlin Series had questioned the role of art in society—indeed, had advocated breaking out of the institutional frame, though had not itself don...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part 1 Contexts and Case Studies

- Part 2 Reflections

- Appendix: Summary of Projects 1975–2016

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Art : Process : Change by Loraine Leeson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arte & Arte y política. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.